Revised Sept 27th 2025.

The dog training world is currently extremely polarized.

On the one hand, some trainers don’t hesitate to use aversive techniques to train their dogs (in other words, they will sometimes inflict pain or discomfort). On the other, we have trainers who will jump through hoops to avoid aversives – or won’t use it at all.

For simplicity, I will call the trainers-who-don’t-think-twice-about-sometimes-using-aversives coercive, and trainers-who-avoid-aversives-at-all-costs positive reinforcement trainers, or R+ . These are just shorthand labels, not rigid boxes.

Yes, I know, I know – that’s an oversimplification. There are many different training approaches out there and some people may feel these labels don’t capture the nuance of their work.

If that’s you, please know no offense is intended. I’m painting with big strokes here only for the sake of the discussion.

I recently ran a poll in the Do No Harm Dog Training group on Facebook, curious to know the backgrounds of the members – had they transitioned from coercive to R+ trainers? And their comments were revealing.

The ongoing evolution in the dog training world.

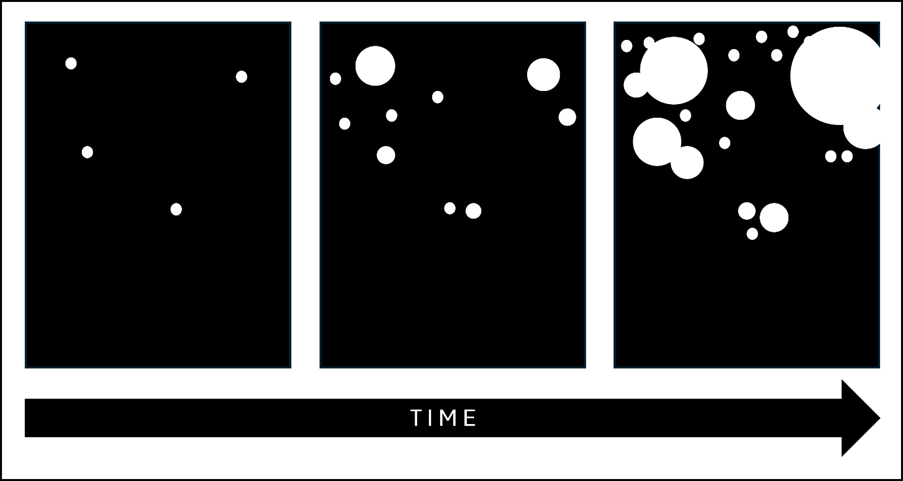

Here’s how I see it: