Why telling the difference between The True Truth and The Fake News is so difficult.

There’s lots of information out there on the internet. And sometimes it’s contradictory.

- About the state of the climate crisis.

- About who won the 2020 US election.

- About how best to train animals.

In this blog post, I will not discuss these topics at any length (although if you’re insatiably curious, I’ll reveal my position on them), but rather beg the question: how do we know which information to believe?

You may think it’s by somehow recognizing truths and rejecting false information.

It’s just that we humans are not very good at doing that.

We very often reject information, even though it’s true.

And we accept information, even though it’s false.

And we all do it.

Every. Single. Person. Does this.

Me.

You.

Aunt Peggie.

Our view of the world is skewed, in some way or another. We’ve all built our personal understanding of the world on a mix of truths and falsehoods. Hopefully mostly truths, but still…

In essence, we all look at the world through partly broken glasses.

Disconcerting as that realization may be, I think that simply being aware that our glasses are partly broken will make it easier to fix them.

The purpose of this blog post is to alert you to your broken glasses, give ideas about how to fix them, and also how to go about helping others with their glasses.

So, why do we reject some information that’s true, and accept falsehoods?

Well, that has to do with how we acquire knowledge. How do we get to know what we know?

To answer that question, we must go back to our pre-historic hunter-gatherer days, which is where we’ve spent 99% of human history.

During that time, we discovered things ourselves.

How to make fire. An axe. A wheel.

And then we’d tell our group: ”Look, here’s how to make fire!” Through verbal transmission of information, and very hands-on, we taught our friends and family what we had learned.

And fast-forwarding through history, then we invented writing – and information could then be transferred not only geographically from one corner of the earth to another, but through time. So now, we can read things that people wrote thousands of years ago.

Today, we stand on the shoulders of giants.

The accumulated knowledge of mankind is at our disposal.

And the accumulated crazy ideas of mankind are also literally at our fingertips, one click away.

So, we’re constantly having to decide whether to accept or reject new information. Assess whether it’s useful and true, and whether it’s worth the effort to assimilate.

And be wary of, or aware of, the risk of accepting false information.

Judging whether a new piece of information is fact – or fake.

This is where cognitive biases come in, and mess things up big time. These biases arose early on in our evolutionary history as a way for us to take mental shortcuts, make quick decisions.

Not having to spend time questioning and analyzing novel information, but simply taking a new piece of knowledge from a trusted person for granted, and also, not being fooled by someone from the rivalling tribe. The archeological record tells us that many early hominids died violent deaths, presumably during skirmishes with other tribes.

In other words, in prehistoric times, there was a compelling reason to trust members of one’s own tribe, as well as assume that strangers were lying bastards literally out to get you.

We are biased to thinking that information from familiar people is true, and information from strangers is false.

And sometimes, those biases result in grave errors of judgment, and this is especially likely to occur if that new piece of knowledge is complex, new, or if we perceive that it’s dangerous. In such cases, these cognitive biases make us irrational, and ineffective.

A certain pandemic comes to mind, for instance – this new, complex threat has really illustrated the extent of the problem with cognitive biases.

And the way I see it, the way our brains work, those judgment errors tend to exacerbate, or even perhaps cause, major conflicts. Whether it’s about politics, religion, and who is the best James Bond actor. Or about whether the climate crisis is overstated, whether Biden really was elected, and how best to train animals.

And in fact, there are two ways that we’re getting it wrong. Two types of biases.

- We tend to reject information from strangers, or novel information, even when it’s true.

- We tend to believe things that we hear from familiar people, and familiar information, even when it’s false.

So, this is the legacy we carry in our evolutionary backpack: trust our tribe, and assume that strangers are lying bastards who are out to get us.

Now, I know what you’re thinking.

“No, no, no, no, no no. No sirree. Not me. I’m a well-educated, modern human. I carefully weigh any novel information on its own merit, discern the fact from the fake, and make informed decisions.”

Sorry to break it to you, but you’re a hunter-gatherer wearing a thin veneer of civilization, and you’re wrong about a bunch of things because of these ancient biases.

Your glasses are broken – and so are mine.

The way to fix those glasses is to become aware of one’s biases. So let’s take a closer look, shall we?

Type 1 biases – incorrectly rejecting true information.

First of all, novel ideas may induce anxiety or even anger, simply because they’re unfamiliar.

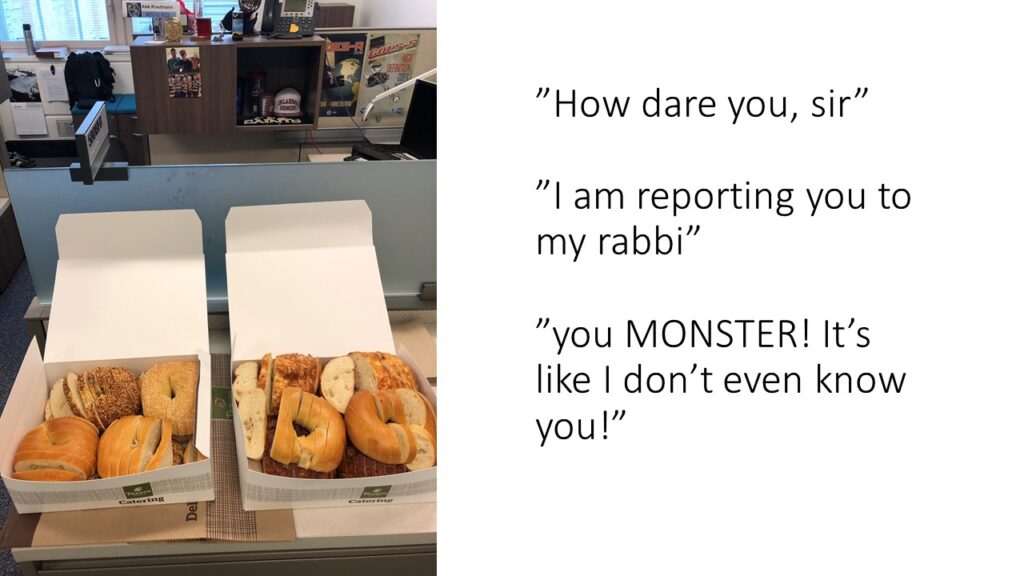

For instance, one guy brought these donuts to work, to share with his colleagues. He sliced them, as if they were bread, and shared the picture below on Instagram.

The post got viral, and many people expressed annoyance at the unorthodox donut serving in the comment’s section.

I find that last one particularly interesting. “I don’t even know you”. As if he were a stranger. And although many of these comments were meant jokingly, we do tend to dismiss or even attack ideas that are new, or that come from strangers.

Again, this is part of our prehistoric heritage. New things could be dangerous. Familiar things are proven safe.

***

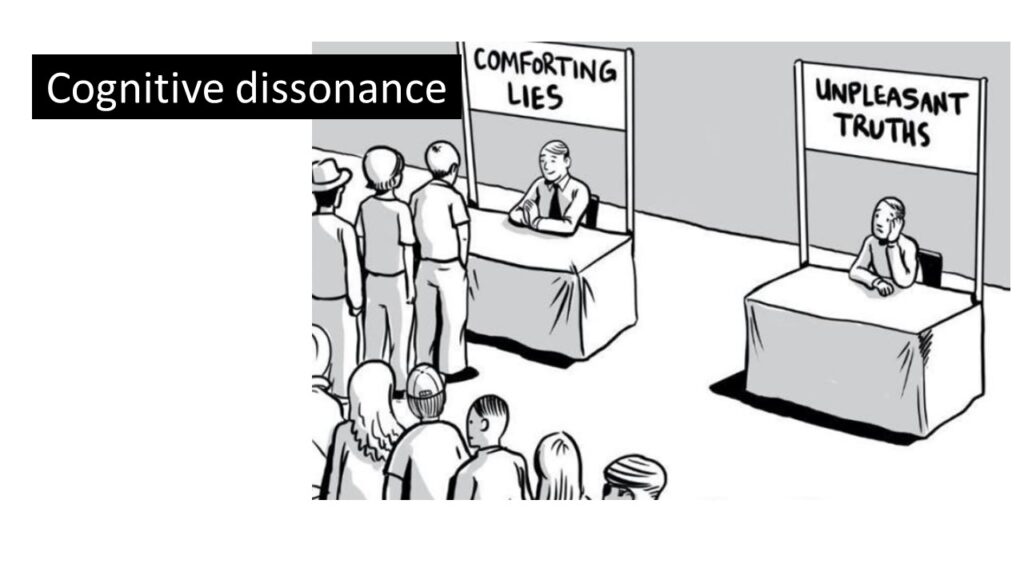

Cognitive dissonance occurs when we’re in a situation involving conflicting attitudes, beliefs or behaviors. This produces a feeling of mental discomfort, which we typically handle by trying to change one of those attitudes, beliefs or behaviours to reduce that discomfort and restore balance.

For example, when people smoke and they know that smoking causes cancer, they are in a state of cognitive dissonance. So, they might try to reduce the dissonance by saying things like “I’d rather have a short, pleasant life than a long boring one”.

And of course, people get into cognitive dissonance if they lovingly correct their dog using leash pops, and then learn that using leash corrections can cause them neck injuries.

Now, the research on dissonance shows that changing behaviour is difficult, it’s easier to change one’s attitude. To make the chosen alternative, whether it’s smoking or leash correcting the dog, a more attractive alternative than the one we didn’t choose.

This whole idea of accepting that maybe some of our knowledge is wrong or incomplete, and that we need to change our opinion or mindset to incorporate new information, is downright painful – and so we often avoid it.

***

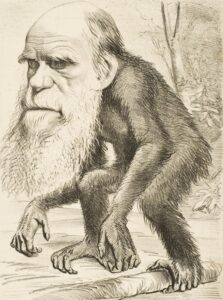

Then we have the Semmelweis reflex: the tendency to reject new evidence that contradicts the current paradigm.

This cognitive bias was named after the Hungarian doctor Semmelweis who discovered that hand washing was a way to prevent infection, back in the 1840s. The medical community at the time wasn’t ready for that because it was believed that sicknesses were caused by bad air, so his ideas didn’t get the attention they deserved.

The Semmelweiss effect, how we tend to reject new findings that contradict our paradigm, is very powerful. We might be slightly hesitant to take in novel information that contradicts some insignificant part of our previous knowledge, but we’re extremely averse to accepting information that turns our entire paradigm up-side-down.

For instance, Darwin was ridiculed for decades before his theory of evolution was slowly accepted by the scientific community.

I remember reading about a study where they put people with really strong political views in an fMRI camera, monitoring their brain activity. As part of the experiment, the researchers would challenge those views. And the brain reactions were really strong, producing an increased activity in what’s referred to as the default mode network—a set of interconnected structures in the brain associated with self-representation and disengagement from the external world. When these emotional structures are activated, people become less likely to change their minds.

When we feel threatened, anxious, we’re less likely to change our minds – our body reacts as if we’re under physical attack. In other words, emotion plays a role in cognition, how we decide what is true and what is not true.

Incidentally, that study also found that we’re more likely to adjust non-political beliefs than political beliefs.

***

Then there’s the backfire effect. The reaction to disconfirming evidence by strengthening one’s previous beliefs.

So, sometimes when we try to convince someone that our view is the correct one, the end result is that they’re even more convinced that they are right. The conversation actually makes things worse.

This is important since it affects both our ability to change other people’s opinion, as well as our ability to process new and challenging information rationally ourselves.

In the animal training world, we’ll often hear people who use shock collars say things like ”No, actually, electric collars are great, they’re not painful at all. The stimulation is just information, it just gets the animal focused”.

If we try to talk to them, we’ll often see this type of backfire effect. They often become even more convinced that those collars are safe – and of course cognitive dissonance is triggered too.

***

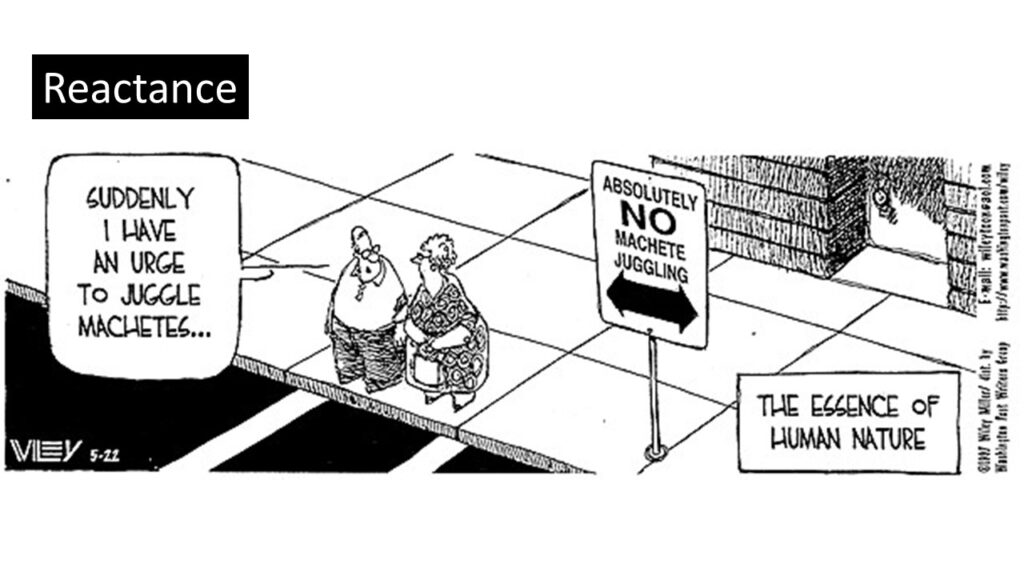

And then we have reactance – the urge to do the opposite of what someone wants us to do, perhaps out of a need to resist a perceived attempt to constrain our freedom of choice.

One example might be a parent admonishing their teenager that “you’re too young to drink alcohol”… That prohibition just makes illicit drinking all the more exciting – and probable.

And of course, people using reverse psychology are playing on reactance, attempting to influence someone to choose the opposite of what they request. Saying to a child: “You really shouldn’t eat that broccoli, it’s terrible”, hoping for a reactance response.

So, to summarize, not only are we likely to reject true information when delivered from strangers, but having a conversation with someone with an opposite view can easily polarize our own views and make us even more convinced that our beliefs – even when mistaken – are correct.

Before we get to what to do about that, let’s have a look at the other types of biases, and check out some mechanisms that cause us to mistakenly accept information that we should reject.

Type 2 biases – mistakenly accepting false information

For starters, there’s anchoring bias.

Think of us all as being attached to an anchor, which is the first information that we learned on a particular subject.

The anchor is our existing knowledge puzzle, and we tend to stick to it, regardless of whether it’s true.

For instance, we tend to judge other people based on the first impression that they made.

We tend to stay with the religion that we were brought up with.

And we tend to interact with animals the way our parents did.

Due to the anchoring effect, we stick with what we first learned – regardless of whether it’s true or not.

***

There’s the bandwagon effect.

Our propensity to join the majority.

If everybody else thinks using a choke chain is great, then it’s likely that we do too.

It’s difficult and uncomfortable to not join the bandwagon, instead of jumping on board being the person who says “No thanks, I’m not going that way. I won’t join you.”

Many of my students have lived through being the only person in a stable saying “I’m going to try positive reinforcement to train my horses”. I admire them immensely for this, because not only is it uncomfortable not to get on the bandwagon with everyone else, but the discomfort can turn really painful, because the people on the bandwagon will typically criticize our choice not to get on it.

A double whammy.

***

The availability cascade is when a new, often simple, idea takes hold in a social group, as a collective belief.

This is when people’s need for social acceptance, and the apparent sophistication of a new insight overwhelm their critical thinking. Seeing a new idea expressed by multiple people in our social group can rinse away any reluctance or hesitance.

Like buying lots of toilet paper in the first few weeks of the Corona pandemic, perhaps, without really thinking it over. Since everyone else did it, we did too.

***

Closely related to this is tribal epistemology – when new Information is evaluated based not on how well it is supported by the available evidence, but on whether it supports the tribe’s values and goals and whether it is vouchsafed by the tribal leaders.

This is where we’ll see in-group favouritism, and how we become loyal to the organizations that we associate with, no matter what they’re saying – or doing.

Apparently, we tend to judge the merit of a political bill not on the actual ideas or wording, but on which party we think wrote the bill. For instance, Israeli Jews evaluated an actual Israeli-authored peace plan less favorably when it was attributed to the Palestinians than when it was attributed to their own government.

***

There’s also authority bias.

We tend to believe people who have authority, regardless of whether what they say is true or not.

That authority may come about because of higher education, a fancy title, fame, or wearing some badge of office, like military insignia – or a veterinarian’s coat.

I remember experiencing the effect of authority bias, first hand.

I was a travel guide in France and Portugal, so during the excursion days I would lecture about local botany, animal life, food and politics, and in the evenings, when I started doing small talk around the dinner table, all the conversations around me would stop, and people would lean in and listen.

It was disconcerting – and exhilarating.

Now, I got a lot of attention in that situation, not because I had something that terribly interesting to say during dinner, but because in the general context, I had authority.

Authority bias can get really scary, and dangerous. As I said, it’s exhilarating to get that kind of attention, and many people risk getting warped and carried away by the adulation of the crowd.

Just think of the mind-boggling ass-kissing inflating the megalomaniac egos of some semi-illiterate, crude, misogynic, greedy bullies – just on account of them being famous politicians. It scares me no end.

And no, not saying any names. This is not that kind of blog post.

***

There’s the illusory truth effect.

Essentially, hear something enough times, and we’ll start believing it.

Is Tokyo the capital of Japan? – Yes, sounds familiar.

Is Baku the capital of Azerbaijan? – Yeah, maybe, rings a bell.

Is there a God? – Yeah, I’ve heard that before.

Should we yank the leash when walking the dog? – Yeah, seen it a hundred times.

It’s familiar, and so we believe it, regardless of whether it’s true or not.

I find this very problematic in today’s Social Media climate, simply that so many unsubstantiated claims are made so often that we can no longer distinguish between true statements and familiar statements – the latter implies the former through the illusory truth effect.

***

Then there’s confirmation bias. The way we pay attention to information that confirms and supports what we know, what we already believe.

We’ll fit new puzzle pieces into our existing knowledge puzzle, even if the pieces don’t quite fit.

If we even bother to pay attention to contradictory evidence, we might ignore it, or not believe it, or somehow reframe it to support our original belief. Our memory will focus on the small detail that supports the original belief – and we may forget the rest.

***

OK; that’s a few of the mechanisms or biases that explain why we tend to accept things we hear often enough and from people we know, like, and trust – even though maybe we should reject those ideas.

The theme is recurring: we tend to embrace familiar information from familiar people, even when it’s false.

And make no mistake, these are powerful mechanisms, and it’s not just stupid people being victims of these biases.

We are all victims of these types of biases.

But wait, there’s more.

Not realizing how little we know – or how much we know

Let’s talk about the Dunning-Kruger effect.

The quote above sums up one part of the Dunning-Kruger effect: when incompetent people are too incompetent to realize they are incompetent. But that’s just half the story.

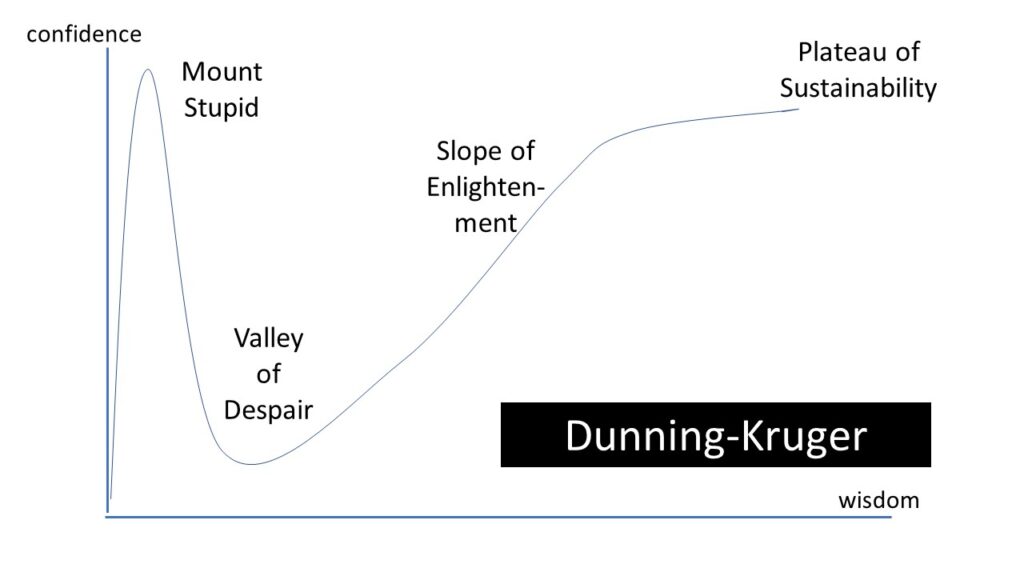

The Dunning-Kruger effect is best explained through a graph.

Wisdom, or knowledge and experience on the X-axis, confidence on the Y axis.

The learning/confidence curve sort of looks like this.

When we first learn something new, we climb Mount Stupid. We learn a little about a specific topic, and we get all confident and excited about this new knowledge.

Back in March 2020, we were all on Mount Stupid when it comes to epidemiology. We’d read a blog post or two, and we became convinced that we knew exactly how to handle the Corona pandemic.

Or at least I did. I was solidly on Mount Stupid for a few weeks.

With time, we learned that the pandemic is an extremely complex situation, and so for many of us, our confidence plummeted as our learning increased.

This is typical, as we learn more about a topic, we realize how much there’s still to learn, and we fall into the Valley of Despair. We get the Impostor Syndrome.

By contrast, the person on Mount Stupid doesn’t know that he’s on Mount Stupid. He doesn’t know what he doesn’t know.

Typically, as we learn more about the subject, we’ll climb out of the pit of despair and enter the slope of enlightenment,

At some point, we reach the plateau of sustainability. See, there’s still room to learn more, it’s just that our confidence won’t keep growing as we’re learning. We’re aware of our knowledge and that it’s incomplete, but we’re OK with it.

Mostly when people discuss the Dunning-Kruger effect, they make the point that stupid people tend often to be on Mount Stupid, and can’t get off it because they’re too stupid.

But I would argue that we’re all on Mount Stupid, only with regards to different topics.

Anything we’ve learned a little about and think we’ve got the hang of.

We’re all on Mount Stupid.

And we’re all enlightened. Only on different topics.

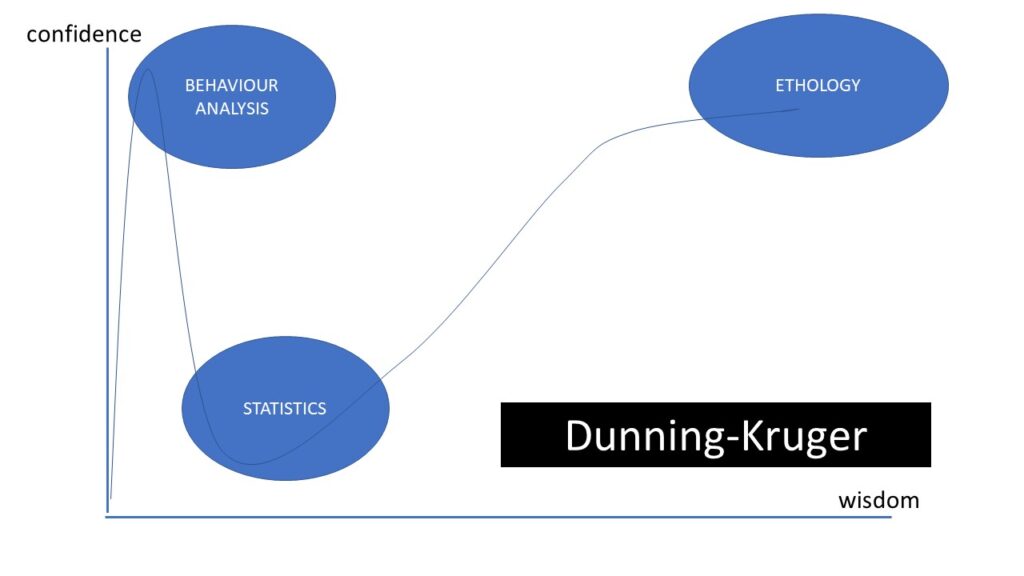

Take me for instance.

For instance, being an associate professor in this area, I know quite a lot about Ethology, and I’m confident about my knowledge. That doesn’t mean that I know all there is to know, there’s still more knowledge to be had, and indeed I’m most certainly misinformed in some areas, but my confidence wouldn’t keep increasing as I learn more.

Statistics is not my strong suit. I know enough to be daunted by it – I’m solidly in the Pit of Despair with regards to statistics – and I’m also not interested enough to keep learning about this topic and get out of there. And I also know that statisticians freak out over all the bad statistics in published scientific papers. In the latest experimental scientific paper I wrote I actually took help from a statistician.

Side note: many other authors don’t take help from statisticians – many scientists are on Mount Stupid when it comes to statistics, and those results still get published. It’s a collective huge problem, having to do with the wrong sample sizes, insufficient statistical power, using the wrong type of statistical method…

Over 50% of publications within the medical field have faulty statistics (bad experimental design, data collection, choice of method, interpretation) – and within the study of animal behavior there’s generally too low statistical power (too small sample sizes) to be able to draw any viable conclusions at all – and yet many hypotheses are rejected without stating power.

As I said, a huge problem.

But I digress, back to my personal Dunning-Kruger journeys.

A while back I came to realize that I was on Mount Stupid when it comes to Behaviour Analysis. Actually, my confidence in that area has dropped significantly since that realization, so perhaps I should put that in the Valley of Despair, nowadays. The thing is that you don’t know when you’re on Mount Stupid. It’s only in retrospect that you realize it.

Another instance when I’m confronted with Mount Stupid is when dog guardians or dog trainers confidently (and often condescendingly) tell me that I can’t teach them anything about dog behaviour because I’m not a dog trainer.

So, time for a little introspection. Where are you with regards to different topics? Which areas of knowledge are your Valleys of Despair? On which topics are you on the Slope of Enlightenment? The Plateau of Sustainability?

And importantly, when have you discovered having been on Mount Stupid?

Being on Mount Stupid is nothing to be ashamed of, it’s part of the learning journey. When at first we learn about a new topic, our confidence in that area soars, before it drops.

It’s when we get stuck on Mount Stupid that we’re in trouble, because confident people share what they know, and during that stage we risk sharing information that is incorrect – we risk feeding the lies, and due to the cognitive biases we just discussed our friends and family are likely to believe us – and strangers are more likely to respond with reactance if we push them too much.

I’m thinking that paradoxically, during the confidence boost while we’re on Mount Stupid, we come across as more of an authority, since we won’t express the doubt we’ll start harboring once we learn more on the topic.

What am I saying?

I’m saying the person on Mount Stupid is more likely to share information than the person in the Valley of Despair, because of the confidence boost. And that information is more likely to be incorrect, due to the lack of knowledge. And finally, that due to authority bias, people are more likely to believe someone on Mount Stupid than someone in the Valley of Despair.

No wonder we’re seeing all these unsubstantiated conspiracy theories – I’m guessing they’re driven by people on Mount Stupid, and catalyzed by that toxic mix of cognitive biases.

So how do we break the cycle? How do we teach effectively, to help people get off Mount Stupid and avoiding the Semmelweiss effect, the backfire effect and reactance?

We’ll get to that, but first; a final cognitive bias (actually, there are plenty more, I’m just listing the most relevant ones for knowledge acquisition in this post).

***

This one is about trying to teach anything to someone who knows very little about a topic. Maybe they’re on Mount Stupid, or maybe not even there yet.

This cognitive bias is related to teaching, and it’s specifically about not realizing how little the uninformed know.

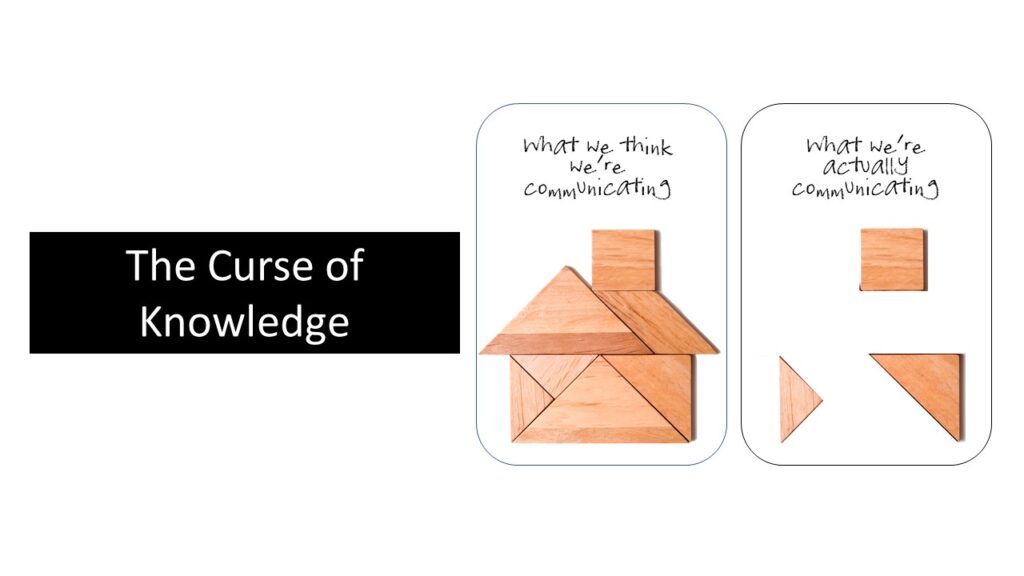

This is called the curse of knowledge.

The curse of knowledge is about how difficult it can be, once you have knowledge in one particular area, to remember what it’s like not knowing anything.

Here’s me discussing the curse of knowledge with regards to animal training.

Normal people on the street have no idea what reinforcement means, or SDs, or counter conditioning, or all the jargon that we animal trainer geeks like to use. We need to speak to them in terms that they understand – without evoking the Semmelweiss / backfire effect or reactance.

***

Now I realize that I have perhaps introduced many new expressions in this blog post. Here’s the most important take-home message: we humans evolved in a situation where we trusted the familiar and distrusted the unfamiliar. We’re likely to accept any information from our tribe regardless of whether it’s true, and reject any information from strangers, regardless of whether it’s false.

So what to do?

Sounds like meaningful discussions are bound to fail, right? Both people in a discussion will have these cognitive biases. What to do about them?

How to fix those glasses

Well, be aware of those cognitive biases in yourself. Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel Prize winner of economics, wrote the book Thinking, fast and slow. In this book we learn that there’s essentially two types of thought in humans.

- The fast, imprecise and easy way, which is automatic and subconscious – and involves all the biases we just touched on.

- And the slow way, the hard way that requires mental effort, which is only turned on when we need to focus.

Now, our brain avoids turning that second system on, it’s mostly in resting mode since it requires effort. Most of our thinking and decision making is subconscious, maybe up to 99%. I’d say we can conquer some of our own cognitive biases by being aware that we have those biases, and consciously making an effort to understand where our knowledge comes from. So switching from the fast to the slow.

Trouble is, we’re blind to our own cognitive biases, but we can often see them in others. So we need to question our own knowledge. How did we learn what we know? Where did we learn, from whom? Why do we believe what we do?

We should practice metacognition: thinking about our thinking. Keeping track of our ego. Is “being right” more important than learning something new? We should reflect on our knowledge base and challenge our own decisions.

We need to listen to people who disagree with us. Don’t just let them speak and wait for the moment where they fall silent so we can sink them and win the argument, but really listen and reflect. That’s what makes having a discussion with someone so interesting. When you discover that you have a difference of opinion on one topic, it’s no longer a case of “I’m right and you’re wrong, you moron!”, but rather thinking “hmm… wonder if this is one of those instances where I could possibly be mistaken? Am I on Mount Stupid when it comes to this topic?”

Consider other options. What if the earth IS flat? Play devil’s advocate, challenge your own assumptions. Apparently, people who engage in debate teams get really good at this, because sometimes the task is to argue one perspective, and sometimes the task is to argue the other perspective.

Thanks to the internet, we can now get help finding both sides of the argument – through procon, for instance.

Appreciate uncertainty. ”I don’t know” is OK. Embrace uncertainty as a stepping stone to rational and well-founded solutions.

Treasure mistakes as opportunities for learning.

And about getting through to other people, I can think of a few things.

- Be friendly, so that the novel ideas that you suggest are perceived as from someone they know, like, and trust rather than from a stranger.

- And introduce novel ideas gradually and non-confrontationally; you want to avoid the Semmelweiss effect, the backfire effect and reactance.

- Don’t ask battleship questions trying to sink the other and win the argument, ask 20 questions with open answers, so you might learn more about the other.

- Don’t blame others for their mistaken beliefs. They’re on Mount Stupid, help them get off it.

- Use memes to make your ideas familiar.

Who knows, maybe you’ll even end up changing your mind.

Oh, before we wrap up, I promised to let you know my stance on the climate crisis, who won the US election in 2020, and how best to train animals.

As to the climate crisis, I think it’s very much real, that it’s urgent, and that we desperately need to vote for politicians who make resolving the climate crisis their absolute top priority, and that we need to get ready for some big changes in the way we live, travel and work.

As to who won the US election in 2020, I believe it was Joe Biden – and that Donald Trump lost a landslide.

And about how best to engage with animals, well, that’s what I normally write about on this blog, and teach through free webinars, Masterclasses as well as full online courses on the topics of animal learning, behaviour, challenges and welfare. Sign up below, and I’ll keep you posted on these events!

References:

Altman. Statistics in medical journals.

Archaelogical evidence on violent deaths.

Jennions, Möller 2003: A survey of the statistical power of research in behavioral ecology and animal behavior

Maoz et al., 2002. Reactive Devaluation of an “Israeli” vs. “Palestinian” Peace Proposal

Pandolfi & Carreras 2014: the Faulty Statistics of Complementary Alternative Medicine (CAM).

35 replies on “Fact or Fake?”

Please could you send over the Training game,? I’m interested to find out more of this. Thank you x

Sue, I’m not sure what Training game you’re talking about? Where did I mention that..? 🙂

17.49 minutes into your video, a ‘stupid little game with cards that you can play” ?

Oh, I see! That had completely slipped my mind! Here it is: https://illis.se/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2025/04/training-game-cars_two-trainers.doc (you’ll need two toy cars or just something small that you can move around like a box of matches)

Thank you x

That was great, Thank you. Oh and you are very musical, I got ‘Happy Birthday by the 4th clap!!

hahaaaa!! I had forgotten about that demonstration! 🙂

Thank you, this is so interesting. A voice of reason in the midst of madness. Especially in these tumultuous times when there are so many opinions and so much information bombarding us daily knowledge of these various effects is valuable. Your example of the latest US election and the authority effect, bandwagon effect etc. is a really clear example of what you have been explaining. Very topical, pertinent and useful.

Hi Fia – so glad you enjoyed this! Even more pertinent now than when I wrote it, I’d think…

I find your writing here so so interesting… I will cintinue on reading your WTF?

A few thoughts I have/had reading so far,

1) Stastics, I think I learned more about life from my statistics class in college with one very simple concept, everything we do involves some kind of probability of 0 to 100%. That means sometimes doing or attempting some action or activity, or believing something or not could have a wide range of being true or working as hoped or expected or not. So I ‘try’ allow my mind to try to calculate/figure out the ‘weight’ of a thing, knowing nothing (or very few) things are black and white. It really encompasses something you described…. “thinking about my thinking”. I ask my siblings sometimes when discussing…. “who is in control of your mind?”

2) reverse phychology…. with my 5 year old grandson…. while his parents would be telling him you have to eat your chicken or vegetables, I would tell him… “don’t eat that, you won’t like it!”, he would look at me as if to say…..f-you you can’t tell me what to do, then he would eat it just to spite me. It worked much better then trying to convince him. I don’t think this would work for my dogs, they are just too honest and non-calculating to fall for that. For them, it is just better to have a straight forward approach.

3) And…. curse-of-knowledge (a big curse for me)…. but I had a thought the other day about dogs and this ‘curse’ …… WHAT DOGS DON’T KNOW, as an area of understanding for the human….. for example, a dog does not know he shouldn’t be pulling you on a leash (he may be thinking that is what you want). A dog does not know there is a border between the sidewalk and street and should not go in street. Many many more things we know but the dog just does not know. How would he know, he never went to school for 12 years and never learned to talk so how would he even know these many things….. of course that is where we are useful to help them learn…

oh, yes – reverse psychology to get kids to eat is a classic! 🙂

[…] At this point I realize that some readers may be discontentedly grunting that I totally misrepresented their branch of science. And that might certainly be true: these short descriptions barely scratch the surface of the scope and depth of these scientific disciplines, and although I’m reasonably well acquainted with them, as an associate professor of ethology I’m very likely heavily biased. […]

[…] about how our cultural upbringing blinds us to ethical problems. A type of cognitive bias. It’s about how if everyone else is doing something, we don’t question it. It’s about how we […]

This is for me one of the best and most intriguing posts that I read further while going through the course on animal emotions. It’s truly very interesting and useful, and sincere.

And if possible please send me training game guide 🙂

Thanks so much Davor, so glad you liked it! 🙂

Wow Karolina… you give us so much interesting information to think about on this course that my brain hurts… but in a good way. Thank you!

Glad you enjoyed this post, Jean! 🙂 Hopefully your brain hurts a bit less after a few days of stewing on this topic! 🙂

Yet another great and worthwhile read. Thank you Karolina.

You’re welcome, Debra!

Your post has come at a most opportune time where I am deep within an animal behaviour course. My make-up is that I love graphs where I add my labels which I believe helps my understanding of what I think I know and where I’m headed.

The course addresses those learning concepts which might cause us to not “believe “. We are taken into our teacher’s lives, we bond with them, lessons are in home settings we identify with, feel comfortable in, we are added to a fb group called a tribe where we support each other.

The imposter syndrome is openly discussed as is progression along the Dunning-Kruger curve (although it’s not called that).

It really is a pleasant, comfortable way to learn.

Thanks for the insights.

Sounds like a fabulous course, Greg – such a good learning environment!

I see echoes of our conversations in the Advanced Animal Training page–it’s nice to know those inspire deep and clear thinking for you, they certainly do for me!

I will add a few more thoughts–I don’t know if they already fall within the ideas you have outlined or not (there was a recent article on the dopamine addition–I think it plays in!).

We get triggered by drama, and the “fight” seems to be addictive. Even among people who are naturally kind, laid back and understanding, they become increasingly defensive (and offensive!) in the face of the tidal wave of polarizing thought and opinion on the internet. In other words, it is really, really, really hard to stay kind in the face of disagreement and constant “attack”.

Hear, hear. It is difficult to stay kind. I sometimes need to cool off – and luckily my husband Tobias is great at stepping in and proofreading things I write that are too poisonous to publish… 😉

YOU ARE MARVELOUS!

Thanks Wendee! 🙂 Glad you enjoyed the post!

Thank you for this very actual blogpost “When you talk you say what you already know. When you listen you can learn something new” – Dalai Lama ( my favorit saying) . We are all sitting in the same bout right now ( this one and only small planet ) animals, nature and Us. Hopefully we can come along, WE CAN if we want ! ..this post showed us how to be humble and vice

Such a beautiful saying by the Dalai Lama!

This is great so many recognisable facts

Thanks John! 🙂

Another brilliant post Karolina. Understanding human behaviour is key to training animals and educating people. May I share this with my students please?

Absolutely, Angela! 🙂

Wow…Brilliant! This is so interesting. !!! Thanks Karolina

You’re welcome, Tine.

Hi Carolina,

I have been following your trainings and advise for some time. I know you are fact based. Since you have reached out of you area of expertise, could you please explain to us in the US how you know that Joe Biden won in a landslide. Please reference the evidence…Thank You.

Thanks for asking, Barb! Just to be clear; I didn’t say I know he won, I said I believe he won… 😉

As far as I have been able to tell, there was no evidence of fraud, Biden won the electoral votes by a decent margin and the popular vote in a landslide, gaining more than 7 million more votes than Trump.

To me it seems that the reason why so many Americans are uncertain about the outcome is that the Republicans have been blasting out the message that it was rigged, and filed over 60 lawsuits claiming the election was stolen. None of them stood up in court – they were all thrown out, because the evidence was lacking.

Find the details here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Post-election_lawsuits_related_to_the_2020_United_States_presidential_election

I think many of the cognitive biases discussed in my post play into this astonishing development. The authority effect: Trump says the election was stolen, so the election must have been stolen. The anchoring bias: Trump said “I won this election” while they were still counting the votes. The bandwagon effect: Trump has, through his rallies, developed a solid, close-knit and very loyal, supporter base. The availability cascade: the Republicans have been hammering the same message consistently for months. Tribal epistemology: there’s massive polarization in American politics (exhausting to watch from overseas..! We have nothing like it!). The illusory truth effect: again, the repetition of the message, simply hearing it enough times, makes it true.

Of course, I’m also suffering under more or less all these biases, just from the opposite side, with the exception perhaps of the anchoring bias since Biden didn’t say he won until he was officially declared the winner. So the problem is, we can’t just assume that either of them won by taking stock in the number of times we hear people say one or the other won. We have to go to the data, in this case the court cases. And they clearly state that there was no evidence of fraud.

I follow historian Heather Cox Richardson, who writes a daily Letter about American politics. Very enlightening:

https://www.facebook.com/search/top?q=heather%20cox%20richardson

Hope this helps!