Revised December 2020 (see bottom of post!)

Training using a clicker is very popular, and is gaining ground amongst animal trainers, but here’s what may come as a surprise to you:

When scientists compare the effectiveness of using a clicker when training to training using only treats as rewards (or reinforcers, to be more precise) outside the laboratory, the results are inconclusive.

One study found the clicker led to faster learning, one that it led to slower learning, and four studies found no difference between the two treatments.

“What! That’s preposterous! I know it works!” some of the most enthusiastic clicker proponents out there may say, and simply ignore those types of publications.

“I knew it!” the anti-clicker crowd may say, and use those articles as ammunition.

For the rest, those types of inconclusive or contradictory data may sow a seed of doubt, a small nagging voice of uncertainty.

And since doubt will likely interfere with your training success, the purpose of this blog post is to dispel them.

Personally, I think those studies have some serious methodological problems that might explain the results. Maybe, as I walk you through my line of thought, you’ll agree with me.

In this post, I will not explain how to train using a clicker, but just assume that you have a basic understanding of how it works. If you don’t, start out by reading this. Or this.

For simplicity’s sake, the term “click” in this post could include any stimulus that’s been consistently paired with a treat, such as the sound of a clicker, a whistle, or a flashing laser light. “Treat” could refer to any unconditioned stimulus that has innately reinforcing properties: for instance food, play, or attention.

So, how does the established clicker work in animal training?

The three functions of the click

A seemingly trivial question, but let’s look at a training trial for a simple behaviour.

You say “sit”, the clicker-trained dog sits, you click and give him a treat.

What just happened? What was the intended function of the click?

- The click predicted treats (it was a reinforcer)

- The click pinpointed the exact moment when the criterion was met (it was a marker signal)

- The click spanned the interval between the behaviour and the consequence (it was a bridge)

So, those were the intended, or potential, functions. Do clicks always have all three functions, or just sometimes?

- Reinforcer. The power of the click as a secondary (or conditioned, or learned) reinforcer depends on the degree of classical conditioning: the number of pairings (click-treat), the quality of the treats, the uniqueness of the combination of the sound and the chosen treat, and so on. The power of the click as a reinforcer is not all or nothing: it’s everything in between too.

- Marker. Whether the click serves a marking function depends on the other information available to the animal in the current setting. Can it get “marking” information from anything else occurring simultaneously? For instance, when the animal touches a target and gets a click at the same time, those two stimuli need to be processed by the animal’s brain – and sometimes maybe the touch will be more salient to the animal, sometimes the click. Animals are hard wired to attend to stimuli; they will orient towards them, approach them, sniff and investigate. Touching is part of the targeting behaviour and tactile feedback will likely be very noticeable by the animal – perhaps more so than the auditory feedback from the click. In addition, nose-touching involves an olfactory component for many animal species: perhaps smelling the target will overshadow the auditory stimulation of simultaneously hearing a clicking sound. Also, how much the animal will attend to the clicking sound will likely be a function of previous exposure to that sound: is it reinforcing?

- Bridge. Animals learn more slowly, or fail to learn the task at all, when the consequences are delayed even by a very short interval after the relevant behaviour. The click predicts the upcoming consequence, so it can lessen the effects of delayed primary reinforcement.

Wow, three-in-one: a marker, a reinforcer, and a bridge! If the click can do all that, no wonder it’s such a popular tool. So, what’s the problem?

Let’s start with laboratory studies of learning.

We expect using a clicker to work

There’s been a lot of work, mainly on rats and pigeons in the laboratory environment, on the effect of conditioned reinforcers (the click being one example) on the acquisition of behaviour. Conditioned reinforcers have been shown to speed up learning, lead to better retention of learned behaviour, produce a euphoric response due to the activation of the SEEKING system and the concurrent dopamine release, as well as improve the resistance to extinction. In the laboratory setting, there’s not much disagreement about the effects of conditioned reinforcers on brain chemistry and behaviour, as far as I know.

The problems begin when we move all these findings to the applied setting. The real world, outside the laboratory.

But before we do that: what do clicker trainers say about their hands-on experiences?

Clicker trainers say using a clicker works

Many clicker trainers speak highly and enthusiastically of the benefits of training with a clicker. They see engagement and focus, they experience speedy acquisition of new behaviours, and that animals remember what they learned through clicker training years later.

They say that it encourages the animal to think for himself, becoming a fully active thinking participant.

They say it makes the animal happy and confident.

In a review including 25 sources, a recent study quoted one trainer:

“Clicker training will turn your dog into a learning junkie – a dog who is eager to offer behaviours and to experiment to get you to reward”.

Those anecdotal reports aren’t very scientific, though. Critics might argue that clicker trainers are biased, ignorant or misinformed. That if you’ve never not used a clicker when training animals, you’re not qualified to make that comparison.

I for one, wouldn’t qualify. I read, write and teach more than I do actual training, and when I do, I do use the clicker a lot. Probably more than I would have to.

But many trainers have trained both using clickers and not using them, so I was interested in their experience.

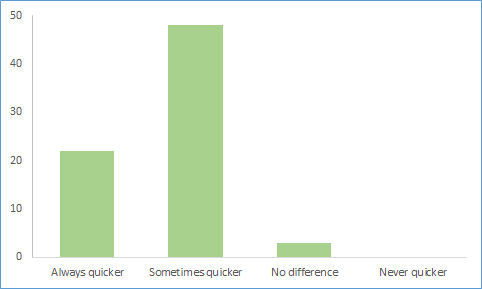

I hang out in a few training groups on Facebook, so I asked: “Those of you who’ve trained both using and not using clickers (or other event markers), which of the following statements do you agree the most with?”

And then they could choose whether clickers always sped up the animals’ learning, sometimes, never, or if they didn’t see a difference.

I know, not the greatest survey. I tend to shoot from the hip, as it were.

Within about 24 hours, I had 73 replies. Within this diverse group of trainers, with experiences from training pets, farm animals, as well as zoo animals: this was the outcome.

So, when scientists started setting up experimental studies, we expected them to confirm what these basic scientific studies, and observations from clicker trainers, have suggested.

However.

The studies published to date haven’t confirmed it.

Current data says clickers don’t work

So, the efficacy of the clicker hasn’t been corroborated by scientific studies carried out in applied settings. In the real world, outside the laboratory, five out of six studies found no difference, or that learning actually slowed down. Only one found that using a clicker when training increased learning speed.

Woops!

So, were the original laboratory data wrong, or are clicker trainers delusional?

Or – dare we ask: are those 6 studies asking the right questions? Looking at the hypothesis from the right angle?

I think not. After browsing those articles with a critical eye, I find a few major problems with them.

Problem 1 – insufficient conditioning

Firstly, in all those studies, they condition the clicker a maximum of 20 times (click-treat, click-treat, click-treat) and then compare the “clicker group” to the unconditioned control group. In fact, in several of the studies, there’s no classical conditioning at all before the operant learning begins, if I read them right.

In other words, the animals immediately start learning the task, one group getting “click-treat” and the other just “treat” as the consequence.

So the animal in the clicker-group both has to sort out that:

- behaviour has effect (operant learning), and

- the clicking sound reliably predicts the delivery of the treat (classical conditioning).

And the scientists start collecting data from trial one. So, if anything, we’d expect the animals to start at the same point, perhaps the clicker trained animals even being at a slight disadvantage because they need to untangle more information than the animals trained with treats only.

In other words, if the power of the click takes longer to establish than the max 20 pairings that any of these studies allowed, the researchers are looking for the effect in the wrong training interval.

They shouldn’t start measuring at trial one but perhaps at trial 150. Or 300. Or whenever we’d expect the reinforcing effect of the clicker to be well established.

Let me explain what I mean by means of an analogy.

In Sweden, we’re just changing our money. We have a new 500-kronor bill, featuring one of the best singers ever to have walked this earth, Birgit Nilsson.

Digression: I once sang in a choir that had the following punisher written into its bylaws: if we ever were conceited enough to think that we’d delivered a first-class performance, we were to listen to Birgit Nilsson singing Isolde’s death aria by Wagner from the 1966 Beyreuth live recording, conducted by Karl Böhm, to put us in our place and expel such foolish notions from our minds. This happened on one memorable occasion: I still remember how the exuberant, happy and proud feelings that we felt when exiting the stage crumbled and deflated as we listened to Birgit’s formidable, impossible and effortless area. Did I mention that her aria was recorded live?

I know, that was weird, and frustrating if you understand learning theory. Rather than celebrate an outstanding performance, we sank it.

Anyway.

Where was I?

Ah, money. So, in theory both these bills are equally valuable right now. We’re in the half a year or so when they’re both available. Now imagine finding one of them on the street. You glance down, and there’s a 500-kronor bill there. About 55 US dollars. 52 Euro.

I wouldn’t get all too excited if I were to find the Birgit Nilsson one – and not because I was punished by listening to her ass-kicking performance on a weird and wonderful evening 15 years ago.

What’s the problem then?

That note is too new.

It’s unfamiliar.

To be frank, I probably wouldn’t even know if it was fake or the real thing. Whereas the other one, with Karl XI, from 2001, is instantly recognizable – I can see a fraction of it and recognize it immediately.

What am I getting at? That conditioned reinforcers acquire their reinforcing properties gradually. It takes familiarity before they can fully evoke a conditioned response.

So, when researchers teach a naïve dog that the sound of the clicker means a treat is imminent, and spends only a maximum of 20 trials conditioning the clicker, that is the equivalent of me finding a Birgit Nilsson- note, rather than the Karl XI-note.

I’d pick it up hesitantly, frowning, turning it over in my hand going “I wonder if this is… maybe?”

I wouldn’t immediately recognize the value of it.

And what I’m getting at is that to the naïve dog who’s only heard a click and gotten a treat 20 times, he’s turning that sound over in his mind wondering if that means what he thinks it might mean.

If anything, we’d expect the click-treat trained animal to be more confused, not less, than the food-only trained animal, in those initial learning sessions.

Back to animals. In a recent review where clicker trainers were interviewed, one said:

“to actually really be a solid clicker training dog would…probably take two months.”

In other words, we expect the click-treat trained animal to diverge from the food-only trained animal in his learning trajectory after a while.

Not instantaneously, which all those scientists seem to be thinking.

Suggestion for the researchers out there:

- If you’re planning to investigate the efficacy of the clicker, do the pairing procedure (click-treat) at least 150 times for the clicker group before you start the actual operant learning experiment.

- Feed the control group the same number of times, so that you’re not introducing a bias in how familiar the animals get with the situation.

- This doesn’t mean that you should do the pairing procedure that ridiculously many times in ordinary training. Then less than 20 is typically appropriate, and the conditioning process will continue as you start operant training. 150 is a semi-random number that I chose with the sole purpose to ensure that complete and utter conditioning has occurred for all individuals in the study. Choosing a lower number risks that for some individuals that hasn’t occurred. I’m not saying that’s what you need for training from a practical perspective, just that when you’re doing research you need to eliminate potential confounds (such as insufficient conditioning before operant learning starts)

OK. So these studies probably didn’t study the reinforcing effect of using a clicker, because it wasn’t properly conditioned, or they chose the wrong interval.

And that still leaves out the marking effect or the bridging effect.

Problem 2 – the operant behaviour contains marker elements

One of the potential effects of the click is that it’s a marker signal, as explained above. The auditory feedback tells the animal the precise moment correct behaviour occurred.

And in all of the scientific studies that have tried to study the efficacy of the clicker in an applied setting, the researchers have used a targeting behaviour as the behaviour under investigation. In other words, a behaviour containing marker elements, so I’d expect the clicking sound to be redundant.

In all the studies, all the animals were taught to touch a cone, or a lever, with their nose. They had visual, tactile and olfactory stimulation helping them to orient towards the stimuli, resulting in the desired behaviour occurring. And since the clicker hadn’t been sufficiently conditioned, it was probably a lot less salient than the other, abundant, information available.

Additionally, some the researchers pointed at the target (the cone or lever), or used luring (showing a food treat next to the target) to get the animals to attend to the stimulus.

In my facebook survey, I received some comments from some very experienced trainers.

Here’s what Stephanie Edlund wrote: (djursmart; understanding parrots)

“It absolutely depends on the behavior for me. If I’m teaching something where I need a clicker, which for me is high precision shaping, picking out a response in a series of responses or other contexts where I can’t deliver reinforcers quickly enough, i.e. animal in the air or far away, then yes, those behaviors are typically learned faster with a distinct marker signal.

When the behavior I want to teach is very distinct to the animal (a bird landing on the hand, butt touching the floor) and I can deliver reinforcement quickly, standing in front of the animal in close proximity, I very rarely use markers.”

Notice that Stephanie refers to the clicker as the marker!

In other words, many skillful animal trainers don’t bother using clickers when target training, because they see no obvious added advantage to doing that. The butt touching the floor, in the case of teaching a sit, is salient enough for the animal, no additional “marking” is necessary. They use the clicker for other purposes!

So, those scientific studies have investigated a behaviour where we wouldn’t expect there to be any tangible difference between the groups.

Suggestion for the researchers out there:

- If you’re planning to study the efficacy of clickers, choose a response where you expect clickers to make a difference compared to the treat-only condition, such as high precision shaping or picking out one behaviour out of a series of potential responses.

- Avoid responses that include obvious external stimuli that can lead the animals to the correct response.

- Don’t use prompting or luring.

OK, so the studies didn’t condition the clicker enough, and they taught responses that clicker trainers wouldn’t even bother using a clicker to teach.

In other words, they didn’t examine the reinforcing properties of the clicker, nor the marking properties. How about the bridging properties?

Problem 3: treats appear immediately

Given the choice of response trained, the researchers were able to present the treat immediately when the correct behaviour occurred.

Specifically, there was no need for a bridging stimulus spanning the time from the correct behaviour to when the consequence occurred.

From the bridging perspective, when do we expect clickers to be the most powerful? When they are used in situations where there’s a few seconds (or more) delay between the behaviour and the reinforcer delivery, such as when the animal performs at a distance from the person delivering reinforcement.

So, from this perspective, we expect the click-treat condition in these scientific studies to be no different from the food-only condition. In both treatments, the animals would immediately get reinforcement for doing the correct behaviour.

In other words, these studies did not test the bridging properties of the clicker either.

Suggestion for prospective researchers:

- In your study, choose to train a response where it’s impossible to deliver the treat to the animal’s mouth exactly as the desired behaviour occurs.

- Rather, choose a behaviour with some distance between the animal and the treat dispenser, so that there’s a few seconds’ interval between the behaviour and the consequence.

Conclusion

The clicker is a tool, and performs best in specific contexts.

Sometimes it’s unnecessary.

Sometimes it’s a precision tool, igniting learning.

If we want to understand how effective training using a clicker is, we need to start by examining it in the context where we expect it to have the largest impact, compared to training using treats only.

That involves looking at reinforcing effects, marking effects, bridging effects, or any combination of these to tease out which has the principal effect on learning speed.

The studies published until now have examined neither, unfortunately.

Additionally, we might want to know what clicker training does for the trainer. As Eva Bertilsson (carpemomentum) said when she responded to my survey:

“My training often proceeds faster when using a marker.

That is, I can get behaviour faster. My feeling is that it’s about me and my capability rather than “the animal’s learning” – if that could be somehow teased apart.”

A very valid point. How does the trainer’s behaviour change when using a clicker, compared to not using one? Both when it comes to the philosophy of training (and believe me, there’s more to “clicker training” than just clicking before feeding within a training session), but also about the mechanics of delivering timely reinforcers and choosing criteria.

After all, it takes two to tango – the animal’s learning is just one piece of the puzzle.

I’m not concerned with the lack of resounding support for using a clicker when training in the current academic literature. The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, and I hope that future research will let us know just how effective clicker training can be – in the right context.

Update December 2020

As far as I can tell, another 3 studies addressing the difference of using a click-treat approach compared to food-only reinforcement have been published since 2017, when this blog post was first written.

In these studies, researchers addressed my second objection, and examined other types of behaviour than mere targeting, and found that indeed, the outcome varied depending on which behaviour was being taught: sometimes the food-only alternative was more effective, sometimes the click-treat condition.

For instance, shelter dogs learned a “stay” better when trained with food-only than with click-food, but there was no difference in how the groups learned a “wave”.

As you may recall, my second objection was about the marking properties of the clicker, and one might argue that when learning the “stay” behaviour, the clicker wouldn’t give any additional information compared to food-only since there’s no obvious behavioural change to indicate to the animal the precise moment when correct behaviour occurs, other than the passage of time.

In other words, there’s nothing to mark. Indeed, as far as I know, most experienced trainers don’t use clickers when training duration behaviours, specifically for that reason: the click doesn’t mark any specific movement, as opposed to when shaping a wave – or a spin. And maybe, since this particular study still suffered from my two other objections, that may explain why the food-only group outdid the click-treat group in the “stay” training.

Another recent study found that when the behaviour was complex (spinning 360 degrees), 3 out of 7 dogs trained with a click-treat learned the behaviour within the allotted time, and 0 out of 8 food-only dogs did.

Yes!

My second objection, that it depends on the type of behaviour trained whether clickers add any value, has been corroborated in the last couple of years!

Two of the new studies still have the shortcoming of performing only 20 click-treat pairings before embarking on the experimental study – in one of them the click-treat trained dogs only got to hear the clicker 70 times altogether!

Again, I think it’s unfair to compare the efficacy of the clicker when it comes to inexperienced learners; we expect that the differences will emerge as the animal becomes clicker-savvy, which I suspect happens over considerably more time than 70 repetitions..! Also, the trainers could promptly reinforce the dogs in the food-only conditions, so my third objection wasn’t addressed in any of these recent papers. My second objection was, though – hopefully the first and third will be, too, in the future!

Come to think of it, there’s a couple of other aspects of clicker training that have not yet (to my knowledge) been addressed in the scientific literature: the euphoric effect, and memory retention (some of the early scientific studies looked at extinction, but that’s really quite uninteresting for the average pet parent).

So, two remaining questions I’d like to see addressed, for all the researchers out there:

- Do clicker-savvy animals show more enthusiasm and focus than food-only trained animals, as we may expect due to the dopamine release that’s documented to be involved in secondary reinforcement?

- And: do dogs trained with click-food remember what they learned better than dogs trained using a food-only approach (also expected, driven by that very same dopamine rush)?

Interestingly, a third novel study found that inexperienced pet owners found it easier to train a nose-target behaviour using click-food reinforcement than when using food-only, which aligns with what Eva Bertilsson said: using clickers makes it easier for the human.

I expect that using a clicker may impact the learner, the trainer, as well as the behaviour being taught. Presently, scientific studies have only looked at a fraction of these perspectives, so I really look forward to upcoming publications in this area!

Please let us know in the comments if you see any such new addition, and I will update this blog post to reflect our new state of knowledge!

***

Did you like this article, and would like to learn more? I write blog posts, give free online webinars, and online courses about behaviour management. Sign up below, and I’ll make sure you’ll be notified whenever something’s going on!

References:

Blandina, A.G., n.d. To click or not to click: Positive reinforcement methods on the acquisition of behavior, Unpublished honours thesis.

Burton (2020). Does Clicker Training Lead to Faster Acquisition of Behavior for Dog Owners?

Chiandetti et al. (2016). Can clicker training facilitate conditioning in dogs?

Dorey et al. (2020) Clicker training does not enhance learning in mixed-breed shelter puppies (Canis familiaris).

Ellis & Greening (2016). Positively reinforcing an operant task using tactile stimulation and food–a comparison in horses using clicker training.

Feng et al. (2018) Is clicker training (Clicker+ food) better than food-only training for novice companion dogs and their owners?

Feng et al. (2017). Comparing trainers’ reports of clicker use to the use of clickers in applied research studies: methodological differences may explain conflicting results.

Feng et al. (2016). How clicker training works: Comparing Reinforcing, Marking, and Bridging Hypotheses.

Langbein et al. (2007). The impact of acoustical secondary reinforcement during shape discrimination learning of dwarf goats (Capra hircus).

McCall & Burgin (2002). Equine utilization of secondary reinforcement during response extinction and acquisition.

Smith & Davis (2008). Clicker increases resistance to extinction but does not decrease training time of a simple operant task in domestic dogs.

Williams et al. (2004). The efficacy of a secondary reinforcer (clicker) during acquisition and extinction of an operant task in horses.

56 replies on “When clickers work”

I taught off leash early puppy socialization and training classes using the Ian Dunbar lure-reward method for decades because it was easier for people and successful. I attended the KPA Advanced Trainer Clicker Academy in 2017 and loved it! I was surprised how poorly I did on my clicker timing when I understood the theory and principles. I do think Gavin’s clicker learning, measured by response consistency, was heightened compared to lure-reward, possibly due to that Dopamine release;-)

What does the Ian Dunbar lure-reward method look like? 🙂

In puppy lessons I prefer to teach my clients a mark word. It still takes some critical learning, but a bit less challenging with the coordination of clicker, hand on lead, and hand reaching for treat pouch. I did learn clicker training in 2005 with a border collie pup I had then and it was very effective, but I find marker word much easier.

I ll try to make a time and see what behaviour i could teach , which doesn t bother me (psycologycally) with and without a click!! i would like to do a scientific work with that!

I ll try to make a time and see what behaviour i could teach which doesn t bother me (psycologycally) with and without a click!! i would like to do a scientific work with that!

I’d like to ask you for permission to translate this article into spanish and post it on facebook

Hi Pablo, and thanks so much – glad you enjoy this blog post! I’ll email you and work something out! 🙂

I still think the TIMING is the most iportant part of training, whatever method you use. If you don’t get the timing spot-on, you don’t get the best results ….

Absolutely. QUoting Bob Bailey about the three most important skills of an animal trainer: timing, timing and timing. 😉

Seen this yesterday with a human client and 5mo Boerboel puppy. She’ll sit reliably but something has gone wrong before my input, so as soon as the treat is offered her sit becomes a stand. I mentioned timing to guardian, but now I think it’s going to be tricky getting pup to stay in the sit. I’m thinking that we will have to ask for sit / mark / deliver treat extra quickly. Or: sit / mark / delay treat a bit while she stays in sit. What do you think? How to unlearn this pop-up?

Seems it’s a behaviour chain. Sit – click – stand – get food. So it’s been reinforced… 😉

I would think of two ways to tackle this: – either deliver food really quickly, or skip the clicker a few times. (And perhaps combine with P-; if the pup stands up while you’re still in the process of getting the food to her mouth, remove or cover the food).

Or perhaps also consider: does it matter? 😉 If it’s not a problem, there’s no reason to fix it..! 😉

Thank you. I’ll try that when I do another lesson with them.

I found this really fascinating. One thing you didn’t speak to, and probably can’t even find out, was the timing/efficiency/experience of the trainer. If the trainers are a bunch of grad students who are not particularly experienced they may not have the optimal timing to elicit the best responses. There’s a learning curve to becoming a competent trainer and an even steeper curve to becoming a brilliant trainer. I’m competent but far from brilliant.

I trained our Eclectus parrot with clicker training. Our dog has had a combination of clicker and mostly other positive reinforcement training methods. (Although the immediate release he gets if he pulls on the leash and stops is certainly negative reinforcement.) My horses have mostly been trained with negative reinforcement but I’ve recently been doing more positive reinforcement and especially clicker training to shape trick like behaviors.

Great point! Timing is hugely important, as is the skill of being an effective shaper. Certainly not something to be expected from the average scientist or grad student..! 😉

I use the word ‘Yes!’ as a marker instead of a clicker because I prefer to take informal opportunities for training and don’t want to rely on always carrying a clicker.

I wonder whether the non-clicker trainers in the studies were silent or if they may have inadvertently used a word as a marker.

Sandy, great question! They were typically silent (although the animal probably instantly learned other predictors, such as the trainer’s hand approaching the treat bag). There’s been a bunch of studies comparing clickers versus verbal markers too, but I didn’t refer to them in this post..! 🙂

Thanks Karolina for another very interesting blog.

When I read it I was wondering. Animals, like humans have their own personality and character. I suppose there are fast and slow learners amongst them as well. So in my humble opinion, shouldn’t the researches take that in consideration as well when comparing different styles of training ?

And what about the way a trainer asks the animal something? Is the cue clear and consistent or changes it a little because the trainer was distracted a little bit or changed his posture or movements?

There is so much more to communicating with other individuals (not only between different species) .

Great question Jeanette. Yes, that’s why it’s important to a) have enough animals in the study so that the sample is big enough to be representative of the population, including both fast and slow learners, and b) to randomize which group (click-treat, treat-only) each individual is assigned to, to avoid the risk of all the fast learners ending up in one group and the slow learners in the other…

And yes, since we might do things a little bit differently each time, it’s also important to have a large sample size. That way, we assume that we’re acting equally variably in both groups – and not more consistent with one group than the other. Those types of inconsistencies makes it difficult to find statistical differences, though, because the data becomes more variable.

I believe there is another factor to take into consideration: how fast the trainer is. With my previous two dags the clicker worked well with the slower dog, I was able to click in time. The faster dog however – small and mercurial – had already moved on to new behaviors by the time I had reacted and clicked… So if a study has both well-matched pairs and pairs with a slow human that could possibly also influence the results…

Yes! Spot on! 🙂

Thank you for sharing your work on “ripping apart” those studies! I’m a trainer for my own dog only. I have, to a certain degree, learned to use a clicker, the same goes for my dog. A little dog, needing small treats, meaning I often fumble getting the treat delivered. So a click makes it easier to mark the behavior I want. I’m aware of what probably is the dopamine effect, if I want to train a calm behavior I might not bring the clicker, because she will be in a state of higher arosal when the clicker is there, I rather say click myself or another marker word

Great comment about the arousal – sometimes we don’t want that! Horse trainers come to mind..! An aroused horse may benefit from omitting the clicker, using low-value reinforcement, having free food accessible, etc..! 🙂

Hi Karolina–I would be very interested in talking with you more about using a clicker as a marker. I recently published a paper on the use of clickers as markers vs. secondary reinforcers, and was pilloried for it. Like you, I think there is more there than meets the eye. In fact, I think it’s entirely possible that animals can distinguish between a marker and a secondary reinforcer…which would be really neat finding if true.

(And thank you for your generous support of our admin team over at DogTraining101! We love your work!)

Caitlin, I find that the definition of “secondary reinforcer” is quite different depending on whether one is a scientist or a (marine) animal trainer..! I wrote about that here: https://illis.se/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2018/03/1ary-2ary-reinforcers-Westlund.pdf

My personal experience from when I first used a clicker was that holding this device made me stop and think: “Erm, ok, when am I supposed to actually use this?”

So the device itself disrupted my training and showed me that before, I had never really thought about what behaviour I expected from the horse. No wonder that my training before was ineffective. How on earth should the animal find out what to do if even I myself didn’t know?

Just another example of a function of the clicker…

Interesting! So, “making the trainer more aware of learning principles”, then…? 😉

Definitely in my opinion. It causes people to plan and thin-slice complex tasks into their clickable portions (slices).

Great point – I think how clickers influence the PEOPLE is much underrated! 🙂

Would make a most interesting research project now that so many more people are showing an interest in learning about using a marker & reinforcer. :-).

When I learnt clicker training the instructor got us to practice using the clicker on a human first. This was very revealing about how hard it is to click accurately and how the dog/human can feel frustrated when not making the right choices. It was great fun too.

oh yes, training games are great! 🙂

That was my introduction to clicker training too!

That’s a great idea!

Great article, thank you.

Another variable to consider when attempting to use the experimental method outside the lab is the skill of the handler or handlers: their timing accuracy and their treat delivery technique.

Also, it would make more sense to first teach each subject a basic skill with clicker training, like targeting an object. Once all the subjects did this to a level of excellence, then introduce a new skill and see how long it takes to learn the new skill.

Since it is hard to do any sort of controlled study with thousands or more horses, the variation found in the results will have a lot to do with individual variation among the sample of horses – their handling history and their innate characteristics. :-).

You’re making a great point, both about trainer skill and variability! Trouble with scientists, most are NOT good trainers.

Interesting read.

Admittedly, I have usually skipped the clicker conditioning and used target training to teach what the clicker means, since touching a target is so easy to learn.

More recently, I find myself not clicking for certain things when training. I suppose it’s for things I’m not really trying to teacg, but rather just an appreciation gesture when things are going smoothly during a task.

But I’m not expert, only a horse owner who tries to teach in a positive manner, reducing the need for force as much as possible.

Where i can get it?

You can get clickers in any pet shop, nowadays… 🙂

Great article Karolina … thanks for the always important consideration that published literature is always worth comparing to non-published experience based anecdotal evidence.

Loves it !

Thanks Ryan!

Yes! Just because it’s peer-reviewed doesn’t necessarily imply that it’s without fault – and we shouldn’t dismiss anecdote just because it hasn’t been published in a scientific journal, either. Maybe just a matter of time before it will be.

That’s a great point and often forgotten ☺️ Really nice to see it spoken about.

🙂

I teach the conditioning of the marker for a whole week. I sell treats in a bag of about a thousand that they go through during this week. Now granted, they are doing some capturing, but I tell them, “for the most part, don’t focus on behavior. Focus on showing them that the click happens everywhere, all the time, for any reason. Click when they are in a different room. Click when you aren’t looking at them. They have to know that their behavior can be rewarded, even when you aren’t paying attention.” The next week I start training the human to capture, lure, and shape behavior. Plus, work on their motor skills on clicking at just the right time.

interesting approach – thanks for sharing! 🙂

A great article Karolina. The methodology works…..

As representatives of science based training it’s really up to all of us to inspire, inform and educate.

thank you – glad you liked it! 🙂

I really liked this article. The first thing that came to mind was similar to what Eva Bertilsson said: maybe the marker is as important to the trainer as it is to the animal. The trainer is very focused on the animals behaviour at the moment of the marker/bridge signal and maybe therefor it is an excellent tool to remember if the trainers sees any progress in the behaviour is is teaching the animal to display. That would make an interesting study!

Indeed! That’s something that’s been completely overlooked in these studies.

Hello Karolina,

Thank you for your post, very edifying.

The articles I have seen appearing online about clickers have been discussing whether the clicker is more effective in comparison with other markers, such as a word or the movement of the trainer to dispense the reinforcement. In this study the conclusion drawn was that the clicker was no more effective than other types of markers.

Do you have any thoughts on this?

Thanks

Julie

Julie, I’ve seen them too. What we know from laboratory studies is that conditioning depends on the uniqueness of the stimuli that are paired. If you use a spoken word, I would make one up or use a word that’s not used in normal language. THere was one study showing that the clicker was more effective than using “good” – but “good” is a common word that could be used in other contexts. IN another study the clicker was compared to “brava” and then there was no difference.

THat it’s not heard outside the pairing context is one thing, but that it’s exactly the same each time is also important to get maximum conditioning. For this reason I would perhaps use a tongue click rather than a spoken word.

Don’t blame the methodology just because of someone’s poor application of it. Bob Bailey.

A Clicker savvy dog can learn much more quickly because it has learnt how to learn. Thank you Karoliner for exposing the flaws in these studies.

Thanks, glad you liked it..! Bob – such a source of great memes! 🙂

Thank you, Karolina, for sorting this out and giving me good arguments!

you’re welcome, Nicki! 🙂

I’d love to see comparison studies of a clicker vs a verbal marker, it might take 150 plus reps to create a clicker savvy dog but I’m pretty sure it doesn’t take that many pairings with a verbal marker, especially if people use it with enthusiasm rather than being dull. There’s a human social evolution that is relevant to dogs, I dont very often click anymore but I do still use markers in training, they are really important tools to me, it’s the piece of plastic that I don’t think is necessary, I think it carries less meaning that our social markers, a clicker might be more useful in less socially driven animals but not dogs, they learn to much on their own to ignore that they learn by social interactions.

Ah, yes, great point about the huge impact of social signals on dogs! 🙂