I find the latest scientific contribution on the issue of shock collars to be frustrating – even outrageous.

Lots of problematic articles are published every day, but this one potentially has far-reaching consequences, and so I feel a lengthy, occasionally nerdy and also somewhat rambling blog post is in order.

I won’t describe the paper down to a T, but lift specific topics that I take issue with, so I encourage you to skim it before reading this post – or not…

In short, the authors found that teaching dogs to refrain from chasing a fast-moving lure was effective when shock-collars were used, however attempting to train the behaviour in a slightly shorter time frame using “food rewards” (50 minutes as opposed to 60 for the shocked dogs) was essentially useless. They also saw no signs of distress in the shocked dogs, except that all of them yelped in pain at some point.

I’m paraphrasing here, obviously.

And I’m using quotation marks to draw your attention to the fact that I’m not quite sure that they actually ever used those “food rewards” as reinforcement for correct behaviour in those treatment groups – the training setup was absolutely bananas, if you’ll pardon the pun (that last bit will make sense in a moment).

TL;DR? Here are the main points of this blog post: - The “food-reward” training was a travesty with a multitude of problems (e.g. dubious conditioning, unwanted behaviour reinforced, no shaping, no assessment of engagement, no calibration of the reward value, adding distractions and distance way too soon, not using a marker, etc etc); no learning occurred - The food-reward dogs got less training time than the shocked dogs - The type of training needed to be successful in the tests was not in the protocol for the food-reward dogs - The “welfare measures” were inadequate and possibly confounded - Generalized fear learning occurred in the shocked dogs, a potential concern for their long-term wellbeing - There was conflict of interest: shock-collar trainers training the “food-reward” dogs - The authors conclude that shock collars may occasionally save lives without considering the risks of shock collars costing lives, which I suspect is on a different order of magnitude - The problems are serious enough to warrant retraction of the paper

We’ll get to my detailed objections in a minute, but first off: I think the chosen approach, comparing several treatment groups, where essentially the only difference in training set-up is whether dogs receive a shock for doing the wrong behaviour, or a treat for doing the correct behaviour, is flawed.

It’s based on the proud tradition from other scientific fields such as biomedicine, whereby you compare two different treatment options, subjecting one group to treatment A and the other to treatment B, keeping all other variables identical in the two groups. And so, the theory goes, you can be sure that any differences between the groups will be a result of different effects of the two treatments, A or B, and not some other random factor such as the weather.

The problem is that training using aversives versus reward-based training (what I’ll refer to as R+ training throughout this post) live in completely different universes. The difference doesn’t simply boil down to the moment the consequence is delivered, whether that’s appetitive or aversive, but there’s large differences in a multitude of other areas as well. These two vastly different approaches simply don’t lend themselves to the standard recipe for comparing two treatment options, the keep-everything-identical-except-the-variable-under-study-approach, what’s referred to as standardization.

In other words, this paper is trying to fit a square peg into a round hole.

There were also many many many other problems with this paper. I’ll touch on the more egregious ones below.

Let’s grab the bull by the horn and look at the “food reward” treatments.

The “Food reward” training.

As far as I can tell, after allowing the dogs to spend up to 40 minutes chasing a lure, on the following day:

- They taught the dogs that every five seconds, a treat would be dropped into a bowl. This means that the dogs learned that treats would occur entirely predictably, rhythmically. The passage of time was the predictor of treats appearing.

- They also said the word “banana” before dropping each treat, intending to teach the animal that the word was in fact the predictor of the treat appearing.

Although they did the conditioning 120 times over the course of 20 minutes, I’d say that we don’t really know whether the dogs conditioned to the word “banana” or the fact that they appeared rhythmically, in which case “banana” would be meaningless noise.

Another concern would be that depending on the size of the treat (which wasn’t stated), the dogs might start satiating, at which point receiving more treats might in fact be aversive rather than pleasant. 120 identical treats in 20 minutes is potentially too much, or too boring. It wasn’t stated whether the dogs kept munching away or stopped engaging.

In short, this is not how most savvy positive reinforcement trainers would go about conditioning a stimulus.

Note that they’re not doing the type of conditioning that’s typically done in most standard R+ training, where the conditioned stimulus is to be used as a marker for correct behaviour, followed by a treat; both of these being in the Consequence part of the ABC contingency (Antecedent-Behaviour-Consequence).

Rather, the word “banana” was in subsequent training used as if it were an established Antecedent (that is, not as a consequence of correct behaviour, but as a recall cue).

As the dog was running away from the handler towards the same lure that he had chased the day before:

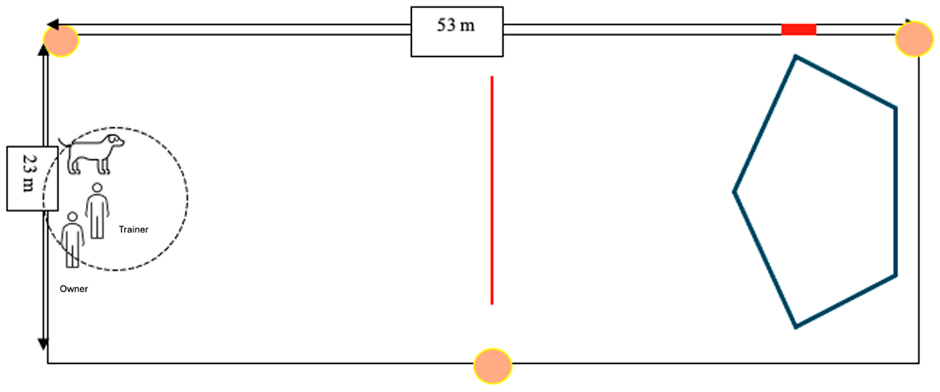

- They waited until the dog was halfway to the lure course, 23 meters away from the trainer, and then uttered “banana”. It’s unclear from the paper whether the word was spoken (which the animal might hardly have heard at that distance) or shouted (in which case the animal would probably hear it, but the stimulus’ pitch and timbre would presumably have changed profoundly from the conditioning session earlier that same day, and that novel sound would thus be less well conditioned, if at all).

- They then immediately dropped a treat into the bowl. Not as a reinforcer, mind you, the animal is still running away (or perhaps skidding across the ground as he’s attempting to come to a halt after hearing “banana”..?). This occurs while we’re still in the antecedent phase – we might call that treat a bribe, or a food lure, maybe – if the animal even sees it.

- If the dog returned to the handler, he would get the treat; if he kept running, they would repeat “banana” (and I assume also drop another treat in the bowl, although this wasn’t stated explicitly for both “food reward” groups) every five seconds for up to two minutes. In other words, the dog might be exposed to several instances of “banana”-and-treat-dropping and ignore it – essentially being exposed to extinction trials.

The observant reader will notice that the setup seems to imply that if the dog ignored the first 20 “banana” and responded to the 21st, he would get 21 treats. And conversely, if he responded to the first “banana”, he’d get one treat. In other words, the dogs were theoretically potentially reinforced for selectively ignoring the recall for a time (or perhaps the repetitive “banana” can be construed as a keep-going-signal, with the altered sound of the last few treats falling on top of other treats in the bowl being the terminal marker) and if so we might hypothetically expect Matching Law to kick in at some point: since waiting for the 21st “banana” pays off 21 times better than responding to the first one, we’d expect the animal to allocate his behaviour accordingly (21 to 1; not that perfect Matching occurs that often, but just for the sake of argument let’s imagine for a moment that it does).

So in theory, the dogs could merrily chase the lure for minutes on end while the trainer kept shouting “banana” at the other end of the field, and then when they started getting tired they might saunter over to collect a huge pile of treats right before the active 2-minute session ended.

What a party! Those dogs would surely have a field day! And after a few minutes rest, the whole circus would start again – this was repeated five times within each of the five sessions.

I don’t know about you, but I find imagining this hypothetical scenario absolutely hilarious – if indeed I’m reading the study correctly and they did drop treats after each and every “banana” regardless of the dogs’ behaviour.

Some other thoughts on the training:

- I’m assuming that by the time the dog was 23 meters from the trainer, they would be fully committed, running at full speed in anticipation of chasing the lure. It’s not surprising that they didn’t pay attention to the “banana” cues – that cue is competing with a very strong distraction.

- “Banana” is apparently used as an intended recall cue, not a marker, attempting to rely on a Pavlovian-Instrumental Transfer – which seemingly doesn’t occur.

- Again, the word “banana” is uttered as the dog is galloping away from the trainer. Due to the lack of previous learning that “banana” is an intended antecedent for “run-to-me-and-get-food”, the animal might rather, through the process of induction, learn the behaviour chain consisting of “run-away-from-me-and-you’ll-hear-the-recall-cue-so-you-can-run-to-me-and-get-food”. In other words, the running-away behaviour might theoretically be reinforced; rather than an antecedent, the intended recall cue can be construed as a marker; a conditioned reinforcer – a consequence of the unwanted behaviour of running away.

- It’s not reported how often the dogs actually got any food, if indeed it served as a reinforcer at all. This is one of the reasons why I hesitate to call this debacle a positive reinforcement procedure: if the animals did not show desired behaviour (and as far as I can tell many of them did not!) they were not exposed to the reinforcement from which they could learn.

- It may be blindingly obvious but still needs to be stated: which behaviour is being reinforced? Yes, chasing the lure: chasing is self-reinforcing. Also a reason why I’m hesitant to call this a positive reinforcement procedure: the correct behaviour wasn’t reinforced (in the sense that it was shown more intensely or frequently).

- The dog was familiar with the environment and had been allowed to chase the lure previously, so previous learning involved “in-this-fun-place-I-get-to-chase-things-woohooo!” Why is this a problem? Because it’s clearly not a learning environment. It’s a place we should only go to once we’d done enough training in a distraction-free environment to be reasonably convinced that the animal would choose not to chase the lure.

- Interestingly, the authors write that the conditioning of the food reward groups was akin to an emergency recall protocol – and then they provide three references. One of those references being what is to me a great protocol described by Pat Miller, a second the FAQ section of Electronic Collar Manufacturers Association (!!) where I find nothing on the topic of emergency recalls, and the third another valid protocol by Saundra Clow. It’s bewildering and misleading that they refer to these two great protocols without following them in the slightest, as far as I can tell.

My main concern with this approach is the assumption that the animal will immediately understand that the word “banana” learned in a different context now suddenly means that he should turn around and run over 23 meters to the handler to receive the treats, although this had never been practiced. And not only that, but he should also abort his hunting mission when he had already committed to it (and some of these dogs were hunting or herding breeds – or young animals with presumably low impulse control, making that particular task all the more difficult). Also, the trainer assumes that the value of the food treat back in the bowl will trump the value of chasing a lure – in an animal who was specifically selected on day one for showing an affinity for chasing lures! The authors didn’t confirm that the food treats used were actually valuable when pitted against something as interesting as chasing lures.

To be clear, this is not training – it is expecting learning to somehow have already taken place.

This set-up is nothing short of ludicrous – I do not know a single skilled R+-trainer who would train this way.

How one might train a recall using positive reinforcement

Here’s some of my thoughts on what skilled R+ trainers might do differently (and for full disclosure, I don’t consider myself a skilled trainer: I lack the practical experience although I’ve learned from countless excellent trainers and understand – and teach – the theory):

- If skilled R+ trainers were to condition “banana” as an intended antecedent rather than a marker (or perhaps we might frame it as a respondent rather than operant approach – which is totally valid by the way!), my guess is that they would probably also do it at least 120 times, but in many different scenarios and contexts – and extended over considerable time, not during one single 20 minute-interval but perhaps in short sessions over multiple days (to allow sleep to help with memory consolidation). It takes many repetitions in many contexts for this association to generalize to the point where it will be useful in a highly distracting context such as in the presence of a moving lure. With this approach, we’d ensure that that PIT (Pavlovian-Instrumental Transfer) actually occurs, and the dog would come running in anticipation when hearing “banana”.

- R+ trainers wouldn’t be disengaged and allow the dog to roam around the pen but rather engage directly with the dog, including perhaps eye contact, praise, and play to build rapport.

- They wouldn’t start making it difficult for the animal (such as adding distance or distractions) before they got some solid indication that the animal had learned the association between hearing “banana” and fabulous things happening.

- They would look at the animal’s body language to assess engagement, and likely do a preference test to ensure that they found something the animal really liked – not take the guardian’s word for it.

- They would use the food mainly as a reinforcer (Consequence) rather than a bribe or food lure (Antecedent) – they wouldn’t present it until after the animal had performed the correct behaviour, which is to return to the handler.

- They might consider using some other reinforcer than food, such as a flirt pole or squeaky toy, to ensure that the animal’s hunting motivation gets an outlet. Some animals might not be reinforced by food when in the mood for chasing lures, but they might gladly attack a furry-or-squeaky-thing-on-a-stick.

- They would bring in the Matching Law: the value of the reinforcer being matched to the difficulty of the task (for instance, whether the distracting lure were moving would perhaps warrant reinforcers of higher value, just as expecting the dog to run 23 meters might warrant a higher-value reinforcer than if the distance were 2 meters).

- They would use a marker signal different from the recall cue to help pinpoint to the animal the moment the correct decision is done, such as turning the head towards the trainer.

- They wouldn’t wait until the dog was fully committed and pelting towards the lure at full speed but give the recall cue earlier in the predatory motor sequence, such as when the dog is eyeing the lure and thinking about engaging.

- They absolutely would not allow the animal to experience the self-reinforcing effects of actually chasing the moving lure whilst ignoring the recall cue.

The authors discuss whether turning off the lure if the food-reward dogs interacted with it would constitute negative punishment: I’d wager that most R+ trainers wouldn’t set up the training so that animals ever were allowed to interact with the moving lure (unless it’s used as a Premack reinforcer, see below). They’d only expose the animal to the moving lure once the recall behaviour was solidly trained and proofed in multiple less demanding scenarios.

Some other thoughts on what skilled trainers might do:

- They would make the task incrementally more difficult, not throw the animal in at the proverbial deep end of the pool. They would perhaps start teaching the animal to recall away from nearby boring things, then nearby boring things that move, then nearby fun things, then nearby fun things that move, and so on and so forth until the animal had built the skill to be able to recall away from moving lures when locked on it at full speed in the opposite direction from the handler, who is 23 meters away.

- They might even use the Premack Principle to teach a solid recall: “if you come to me when I call you, I will then send you out to chase the thing that you find so interesting”.

- If things were not working, they would change their behaviour rather than keep repeating the same thing and expecting the animal to change his behaviour. They wouldn’t keep saying (or shouting) “banana” every five seconds and chucking food in a bowl while the animal was busy blissfully chasing the lure 30-odd meters away for 50 minutes.

Most importantly, a skilled trainer would train for the situation – not in the situation.

See why it’s impossible to treat all animals in a research study involving the study of the efficiency of positive reinforcement in the same way? They are not genetically identical, unlike those inbred rodents! They have different personalities and quirks, preferences and phobias, and need to get individualized treatments. They don’t live under standardized conditions in a lab, but spend the time outside the experiment with their (probably highly diverse) owners in different homes. And importantly, they can’t be on a timeline – the decision to move on in the training schedule can’t be based on the number of minutes that have passed, but on whether the animal has understood what is being asked, and is willing to play the game.

Can you teach a solid recall with a dog you don’t know in 50 minutes?

The authors wrote: “For a fair comparison of the training techniques, we needed a protocol with a time frame matched across groups.”

Yeah… if that time frame were generous.

The problem is that we don’t know whether the time they allotted was indeed fair. Perhaps the food-reward groups would have learned eventually, after 6, 60 or 600 sessions (although, since they were continuously self-reinforced by being allowed to chase the lure, I doubt that they ever would have). Perhaps, if skilled R+ trainers had been involved, they would have learned after 30 minutes? 90 minutes? 4 hours? 12?

I suspect that 5 sessions – 50 minutes of training – might not be enough to achieve the intended results with a completely naive dog unknown to the trainer. Full disclosure though: I’ve never owned a dog, much less trained one to recall, so I really don’t know.

However, we don’t expect the different groups to learn within the same time frame – I would actually predict that the shocked dogs would learn this particular task quicker, due to negativity bias and one-trial learning. Aversive conditioning works fast: animals quickly show suppressed behaviour and learn to avoid situations associated with pain. Appetitive conditioning for this type of scenario is, I expect, comparatively slower, since more repetitions will be needed. So, the experimental design needs to be based on an estimation of the time it will take to perform the (perhaps slower) appetitive conditioning on the R+ groups, not on the time to achieve the (perhaps faster) aversive conditioning on the shocked groups.

Some thoughts on the results

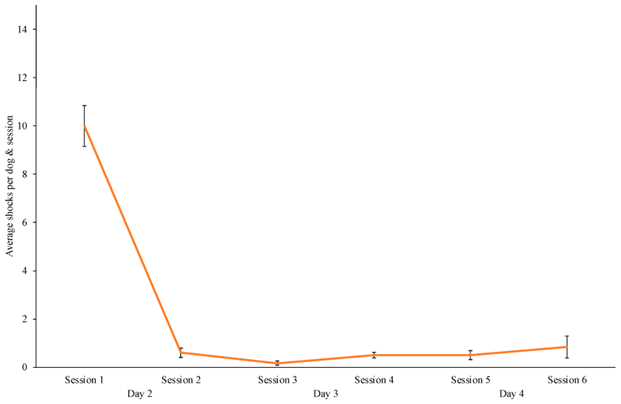

The shocked group was mostly shocked in session 1. It wasn’t stated whether they still approached the lure during subsequent sessions but responded correctly to the word “banana” or if they started avoiding the lure altogether, or when that transition happened. However, this was tested on the last day and found that the animals had indeed developed avoidance in the training arena (which in turn implies fear learning, an insidious welfare concern that wasn’t mentioned in the paper).

The dogs trained during five or six sessions (50 versus 60 minutes of training in total), after which they were subjected to four tests on the final day.

- In the first test, the lure was deployed, and when the dog crossed the pre-determined threshold 23 meters away, they said “banana”. The dog was noted successful if he then responded to the word or didn’t cross the line, and unsuccessful if he chased the lure. All shock-trained dogs succeeded, all “food reward”-trained dogs failed this test.

- In the second test, the lure was deployed, but they did not say “banana” when the dog crossed the threshold line, and in test three the dogs were left alone in the training arena (I suppose the lure was deployed in test 3, even though it isn’t stated.) In these two tests, the authors assume that by now, the animal should have learned that “it’s round about here that I hear the warning / recall, I had better not continue forward”, or perhaps “it’s around this distance from the moving lure that I hear the warning / recall, I had better not continue forward.” And while this might be true for the shocked dogs, the food-reward dogs had been hearing “banana” every five seconds while running after the lure during training, so we can’t expect them to have learned to expect a recall specifically at the threshold line. For that to have occurred, it would have to have been trained: we would have to have taught the animal that “if I stop and then reorient to my handler at this location where I through massive repetition have learned to expect to hear a recall cue, I get treats”. In other words, test 2 and 3 test the food-reward dogs for something they were never trained for – even if we assume that the basic training as described above had been successful and the dogs had started responding to the recall; it was not in the protocol. For the shocked dogs it’s another story: this type of generalization is expected because of fear learning. All shock dogs succeeded, all food reward dogs failed these two tests.

- Test 4 took place in a novel arena with a novel lure, and mimicked test 1. Not surprisingly, the food-reward dogs failed this test and chased the lure – and so did 1/3 of the shocked dogs – they did not respond to “banana”.

In my mind, test 4 is the really relevant one: will the dogs show behaviour that can literally save their lives and respond to a recall cue in a context for which they have not been trained? And it certainly would be interesting to see if dogs trained by skilled R+ trainers could top the 67% shown by shock-collar trained dogs in this study after 60 minutes of training.

Also, two dogs were excluded from the study because the number of shocks they were given exceeded 20, which was what the ethical permit stated as a maximum. Simply reading the paper, this seems to imply that only 75% of shocked dogs succeeded, but on social media the second author has clarified that it was only in retrospect, after all training was concluded, that they realized that those individuals had received more than the allowed number of shocks and were therefore removed from analysis, but as far as I understood they had in fact completed the training and tests, and also learned the avoidance behaviour.

The “welfare measures”

OK, so I brought the brackets back because I don’t think that the authors successfully explored whether the animals’ wellbeing was affected by the choice of training approach.

They filmed the animals during the training, and independent observers scored a range of different behaviours. Sidenote: the video coders were blinded – that, to me, is like putting a bandaid on a broken leg: it doesn’t matter whether they were blinded or not since the set-up of the study was so fatally flawed.

- As far as I can tell, behaviors were not coded or analyzed during intertrial intervals or outside of training sessions but only during the training or test sessions when the lure was deployed. This is a glaring omission as it’s not unreasonable to expect differences to be shown after the adrenal rush of the chase had subsided.

- The ethograms didn’t contain body language measures relevant to assessing distress, such as tail carriage, ear position, flinching or crouching. The behaviours possibly indicative of reduced welfare measures were vocalizations, yawn, shake-off, and scratching – but apart from vocalizations, they occurred infrequently and were not analyzed. Hence, we don’t know if those few behaviours were shown by the shocked or food-rewarded animals, and which moment in time they occurred in relation to relevant events such as shocks.

- The fact that 33% of the shocked dogs would not approach a moving lure in a novel context is seen as a success by the authors. I see a generalized conditioned fear response – a huge red flag for future welfare problems and side effects not mentioned in the paper.

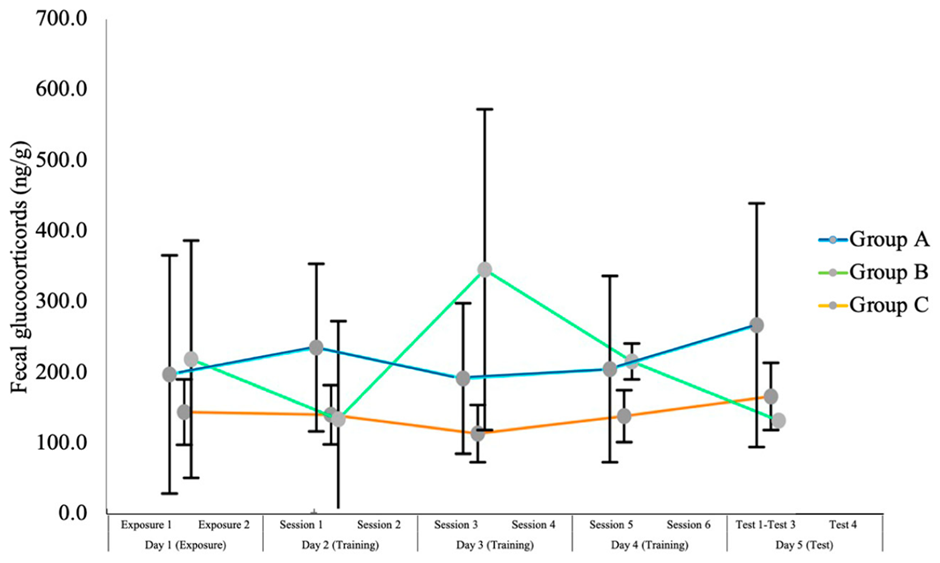

Also, they measured fecal cortisol, which in my mind is problematic in several ways:

- Cortisol is a measure of arousal and might indicate both positive and negative emotional states. Since the food-reward animals were allowed to chase the lure, I would expect a lot of positive emotional arousal, which is a potential confound.

- Fecal cortisol gives a summary reading of the approximate level of arousal 24 hours before, so I’m not even sure how I should read the figure below. Is the “day 1 (exposure)” data actually indicative of the animal’s physiological state on day 1, or day 0? And how is an average of 24 hours even relevant – most of that time is uncontrolled since training only occurred 20 minutes per day? I would rather suggest looking at saliva cortisol within minutes of the potential stressor to see whether the arousal was different in the shocked versus non-shocked dogs around the moment when it matters, and if and how it abated in the shocked dogs (but see my first objection above).

- The authors write: “Only 9 of the 19 dogs provided a fecal sample on each study day: four from Group A, two of which were removed from analysis because of the exceeded shock levels; one from Group B; and four from Group C.” If there’s only one dog from the B-group then why are there standard error bars? Or is there a mix of dependent and independent data in the graph?

- I find this graph confusing – I’d much rather have seen individual data points to get a gist of each individual’s journey – and to know if those individuals shocked the most scored differently than those shocked fewer times.

- I’m assuming the single Kruskal Wallis test reported compared the dogs’ group mean cortisol values over all 5 days – and in such case if the stress effect of the first few day’s shocks might have petered out – so in my mind this would not be a valid approach. Not that I even think the KW test is valid, seems that with sample sizes of 2-1-4 the test shouldn’t even be attempted (statistics is not my strong suit, but the recommended minimum sample size per treatment seems to be 5).

- The authors wrote: “To ensure that the dog did not develop any conditioned fear to the training arena beyond the avoidance of the lure, between sessions, the trainer and owner walked around the field, as needed, and encouraged the dog to move around.” Which behaviours did they show (if any?) that indicated that walking the area was warranted? That’s not explained in the study. But the fact that the shocked dogs chose not to cross the threshold line on the test day (tests 2 and 3) suggests that they had in fact developed conditioned fear to parts of the training area (presumably the locations where they had been shocked), despite this intervention.

- Many of the breeds in the study have high prey drive, prone to instinctive chasing behaviour (hunting / herding breeds) – so not only does this study punish dogs for doing what they were explicitly bred to do, but these results might not be generalizable to the average dog population.

The authors write: “we were mindful of the concern of stimulation habituation that occurs when animals are exposed to gradually increasing shock intensities and were cognizant of the literature advocating for administering the most intense, punishing stimulus without causing damage.” This to me is a welfare concern in and of itself: the setting is completely arbitrary and what is extremely painful to one dog might be barely noticeable to another: there’s simply no way of knowing where on that scale that setting was for each individual. What we do know is that all the shocked dogs yelped in pain at some point during the training.

In short, neither the behavioural nor the physiological data collected was well designed to capture any short-term welfare related concerns – and the authors downplayed or ignored the welfare concerns that they did find. 100% of dogs yelping in pain, the results of tests 2 and 3 explained by fear learning as well as signs of generalized fear conditioning for some dogs. Also, 33% of them did not respond to “banana” in a novel context. This to me implies that further shock training would be used to ensure higher reliability in the future, and in my mind, the insidious risk of going down that track is reduced long-term wellbeing when exposed to repeated stressors, as has been well documented in other studies. Animals may resiliently bounce back from the occasional and rare aversive experience, but chronic stress might set in if those stressors are too frequent or too severe.

Training with R+ doesn’t carry all the well-documented fallout associated with the use of aversives, such as potential fear, aggression, apathy, learning difficulties, etc etc.

The study is called “Comparison of the Efficacy and Welfare of Different Training Methods in Stopping Chasing Behavior in Dogs”. I think this is a misnomer – neither efficacy nor welfare was studied. “Shock collars hurt and may lead to generalized fear learning” is the only reliable welfare-related observation we can make from this study.

Now we’re getting to what is to me the biggest problem with this study:

The Conflict Of Interest.

The issue of whether to use shock collars on dogs is tremendously controversial, and the two camps involved in the discussion are both trying to prove to the “other side” that their approach is backed by science.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

They write: “In response to criticism of some prior studies, we used the same two trainers for all training conditions and, as far as practicable, designed protocols with single contingencies”.

Well, the trainers would then need to be a) equally skilled in both approaches and b) not have a vested interest in the outcome of the study.

As we’ve seen, the first prerequisite didn’t hold, and in my opinion, the second doesn’t either.

When a well-known balanced trainer eagerly promoting the use of shock collars, together with his mentee, carries out both the training of the shocked group as well as the two “food-reward” groups, my warning bells go off.

And he doesn’t simply carry out the training as specified by the authors, the training set-up is specifically based on his recommendations.

The main trainer is not neutral – he’s biased. He has a vested interest in the outcome of the study, even if he’s not one of the authors.

And indeed, not only do they carry out the “food-reward” training as a travesty that has every skilled R+ trainer scratching their head, they give the shock group unfair special consideration:

- They calibrate the shock for all the shocked dogs, assessing their individual motivational state. They do NOT calibrate the intended reinforcers for the individual food-reward dogs – they don’t assess their motivational state. The authors write that some of the food-reward dogs in one of the groups “stopped moving towards the lure on hearing “banana” but did not return for the treat” – this suggests that the treat wasn’t reinforcing enough in that context, given the distractions and distance needed to travel to obtain the treat. Also, during the training phase, the authors write that one dog “… either laid on top of the motionless lure and did not respond to “banana” or laid at the starting point and did not follow the owner to approach the threshold line.” This glaring failure is in my mind equivalent to an animal not responding to the shock collar – and yet nothing was done to help this dog be successful. Whatever they did, it is clearly not positive reinforcement.

- They ensure that the shock groups understand which action is being punished by taking care to shock the dogs when they make contact with the lure. The food-reward groups don’t ever learn which behaviour gets reinforced, apparently.

- They walk the shocked dogs (and some of the food-reward dogs) in the arena to prevent fear learning and associated unwanted behaviour (although no data is given, we don’t know whether this was done preventatively with all dogs or if they were showing actual avoidance behaviour that was addressed). They do NOT prevent the food-reward dogs from practicing the unwanted behaviour of chasing the lure – which is self-reinforcing and reduces the likelihood of them responding to the recall – the equivalent of an extinction trial. In my mind, they’re setting the shocked dogs up to succeed, all the while setting the food-reward dogs up to fail.

- Shocked dogs had one session more of training (six) than the food-reward dogs (five), since the conditioning (“banana” equals treat) occupied their first session. The authors downplay this: “This may have placed Group A [shock] dogs at an advantage when they entered the tests but, given the magnitude of the differences in the performance of the three groups at the end of Training Session 5, this seems unlikely”. I disagree: I would expect the shocked group to learn the behaviour relatively quickly, and the food-reward groups to catch on gradually (at least if the training was up to par) – but since their time was cut short they might have been at a disadvantage. The authors don’t share the data from the different training sessions, so the reader has no way of knowing if any progress at all was made and if that final session might have added any value.

The authors write: “We designed our study around current trainer practices”. I would say that is blatantly untrue. Rather, they designed a biased study that showcased one approach while setting the other up for failure. Indeed, the blatant conflict of interest to me invalidates the entire study.

Also, it seems to me that we need to rethink how to design such a complex task as a study comparing different training regimes. Indeed, there is a reproducibility crisis in the biomedical field, and the concept of standardization has lately been questioned; one solution seems to be heterogenization. One such heterogenization tweak would perhaps be not to have one or two trainers train all the animals, but multiple trainers training multiple animals – this would put to rest the concern that one group of dogs may fare better because of a difference in two single trainers’ skill at their craft.

The fallout of shock collar training

The aversives may “win” in the short run, quickly stopping the unwanted behaviour in at least some dogs sometimes – but the potential fallout often comes later.

It’s troubling that the paper comes off as condoning, or even promoting, the use of shock collars – and doesn’t do a good enough job of addressing all the inherent pitfalls.

I’ve covered the possible side effects of punishment elsewhere, but I want to address the author’s concern that shock-collar training can sometimes be life saving – when for instance a dog risks being run over by a car after running into the street.

And while I’m not disputing that risk, this study implies that the only way to avoid that tragic outcome would be through shock-collar training – and I assume, the dog wearing a shock collar every time he’s off leash, just in case he no longer responds to the call “banana” – as was the case in 33% of shocked dogs tested in a novel arena.

I would turn the tables and say: rather than discuss the number of dogs who can potentially be saved from getting hit by a car through shock-collar training, the question we should ask is: how many dogs will be relinquished and euthanized because of shock-collar training?

I would suspect that number is on an altogether different order of magnitude. As any behavioural consultant or shelter will tell you, the fallout is huge (there’s probably data out there somewhere, if someone will graciously point me to it I shall incorporate it ASAP).

The trainers conducting this study are renowned in their field and considered highly skilled at shock-collar training (but I must say that I find it really sad and disheartening that the animal isn’t in any way acknowledged or rewarded for aborting the chasing behaviour) – and still, only 67% succeeded in doing a recall in a novel scenario, and all dogs yelped in pain when trained.

I can’t imagine that a novice trainer would do better and achieve a higher success rate – quite the opposite.

Given the limited effectiveness, coupled with the ethical consideration and the documented risks associated with aversive training, I think aversive tools such as shock collars should be banned, not the least because of the risk of malfunction (apparently, it’s not unheard of to find dogs having burn marks despite only having been exposed to the sound setting).

Perhaps if they were banned, trainers using shock collars would actually bother to learn how to go about training a reliable recall using R+ techniques..?

This poorly executed training does in no way, shape or form reflect the approach of a skilled R+ trainer. It’s like pitting a runner against a cyclist in a 400 meter race – without bothering to teach the person how to ride a bike. The comparison is deeply unfair and given how high the stakes currently are in the dog trainer universe, such appallingly inadequate training should not be used to settle the issue.

Finally, the journal in which this paper was published has been flagged as predatory (charging publication fees without providing standard peer-review or editing services). Notably, the time from submission to publication was 25 days, which is extremely short. Given the many problems with this paper, I doubt that a proper peer review was done.

Despite the author’s claims, it didn’t convincingly demonstrate that shock-collar training doesn’t compromise welfare, nor that R+ training is not effective.

This study ought to never have been published – I think it should be retracted.

***

Edit: I’ve had people tell me that although they think reward-based training sounds interesting, they’re concerned that it might be impossible using reward-based training to train especially high-drive breeds- something that the skilled R+ trainer colleagues I’ve spoken to disagree with, saying it can absolutely be done.

Makes me think of that Chinese proverb: “Those who say it can not be done, should not interrupt those doing it.”

Which brings us to Henry Ford’s: “Whether you think you can, or you think you can’t – you’re right”.

So, if you’re among those thinking that it can’t be done, I invite you to suspend your disbelief and give it an earnest chance! ❤️

Sharing a video from Josefin Linderström on some of her student’s dogs, including some of the training and before-and-after, and featuring a beagle/mountain curr, an amstaff and a malinouis/cattle dog among others, all of whom had strong prey drive before training started.

Josefin does a webinar called Tattle Training: turn triggers into cues where she teaches these techniques.

Several other trainers specialize in helping overcome predatory behaviour. You may want to check out Simone Mueller’s Predation Substitute Training, or Alexis Davison from UnChase, also!

If you found this interesting, you might consider signing up for my newsletter. I’ll keep you posted on the odd blog post, podcast, online summit, webinar or Masterclass, all on the topic of animal emotions, learning, behaviour and welfare – and I’ll also let you know whenever one of my full courses opens for enrolment!

36 replies on “A critique of the “banana” shock collar study”

It’s not a comprehensive list by any means. If anyone wants to add to it, I’d be delighted to read more.

Replicability is meant to help confirm study findings. What might happen if the study was repeated with all the same design elements etc? What would happen I wonder? Who would take it on?!

I think it would be ethically dubious to replicate this study down to the last detail since the “food reward” training setup was so bonkers. I would expect similar outcomes. The experimental design would have to be substantially revised.

[…] is a poorly designed study that seems to have passed into publication much more quickly than is normal in the peer-review […]

I cannot see that this study moves knowledge forward in any degree considering that we have at least 20 years of similar papers that compare R+ and P+ effects in learning and training dogs (and other animals).

Quite apart from serious flaws in the study design and execution, I cannot see how any ethics committee could now approve the use of shock collars anymore than they would (I hope) not agree to another experiment like the Overmier and Seligman 1967 one that shocked dogs in order to demonstrate learned helplessness.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts, Charlotte! My view is a bit different: it’s legal to use shock collars in many countries (including where this study was undertaken), and it’s being done; dogs are exposed to this type of treatment every day – indeed, perhaps those very same individuals would have been trained that same way regardless of whether a researcher was observing them (but then there would have been no limit to the number of shocks potentially given).

Sad and outrageous as it is, that is the state of affairs – and I think if we can learn anything from this that will help us get them banned, then those studies should be done. In this one we learned that shock collars hurt and that the effects don’t generalize that well (despite claims often told that it’s “just a little tickle”, and that there’s almost 100% reliability with shock-trained).

see exactly where you are coming from, but surely, after 20 years of studies, most of which are much better than Clive Wynne’s, we no longer need to shock dogs to prove that it hurts. We even have a studies that show that the level of shock from collars is impossible to control, not cited in Wynne’s study and not considered in the limitations. This is the link to the latest such study, in case you have not seen it. (https://repository.lincoln.ac.uk/articles/journal_contribution/The_characteristics_of_electronic_training_collars_for_dogs/24405244).

When a study is this poorly constructed and undertaken with such limited skill, it simply adds fuel to the P+ community. Most people will not or cannot read it with the requisite level of criticism and understanding of the science that underpins R+. I doubt that the people who resort to a shock collar will consider it with nuance but simply regard it as a quick fix. Maybe some as a last resort. This study will support their arguments, not ours. Its conclusion, after all, is that shock collars do have a rôle in training.

Many animals and sometimes humans have suffered greatly in experiments and we too stand on the shoulders of the pioneers who undertook them, but now we have ethics committees for a reason. Would we sanction Martin Seligman’s experiments today to replicate his experiment on learned helplessness? I hope not.

It’s not about censorship or an unwillingness to fight the R+ corner. In a way, this study does provide an opportunity for the R+ community. However, I believe that our efforts are better used in fighting for legislation to ban shock collars – an ongoing battle here in England and Wales where legislation has been kicked into the long grass since 2018. This study supports the legislators who argued, when the legislation was debated in Parliament, that shock collars are the only way to train dogs not to chase livestock and wildlife. It is a significant problem here and we urgently need owners to train with effective methods for the sake of farmers as well as dogs.

I find it extraordinary that there is no cognitive dissonance for Clive Wynne, the man who after all chose to write a book entitled Dog Is Love highlighting the science underpinning dogs’ attachment to man.

I see where you’re coming from, Charlotte – and I will happily admit that I am not that well read on the scientific literature related to shock collars used on dogs. Your argument is compelling…!

I just did a selective literature review on the subject if anyone wants to read further:

Blackwell EJ et al (2008) The relationship between training methods and the occurrence of behaviour problems, as reported by owners, in a population of domestic dogs, Journal of Veterinary Behaviour, V3(5), pp 207 – 217

Casey RA et al (2021) Dogs are more pessimistic if their owners use two or more aversive training methods, Scientific Reports, V11(19023), https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-97743-0

China L, Mills DS and Cooper JJ (2020) Efficacy of Dog Training With and Without Remote Electronic Collars vs. a Focus on Positive Reinforcement, Frontiers in Veterinary Sciences V7:508, doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.00508

Deldalle S and Gaunet F (2014) Effects of 2 training methods on stress-related behaviours of the dog (Canis familiaris) and on the dog–owner relationship, Journal of Veterinary Behaviour, V9(2), pp 58 – 65

Fernandes JG (2017) Do aversive-based training methods actually compromise dog welfare?: A literature review, Applied Animal Behaviour Science, V196, pp 1 -12

Hall NJ et al (2021) Working Dog Training for the Twenty-First Century, Frontiers in Veterinary Science, V8:646022

Hiby EF, Rooney NJ and Bradshaw JWS (2023) Dog training methods: their use, effectiveness and interaction with behaviour and welfare, Animal Welfare, V13(1), pp 63 – 69

Maier SF and Seligman MEP (1976) Learned Helplessness: Theory and Evidence, Journal of Experimental Psychology, V105(1), pp 3-46

Maier SF and Watkins LR (2005) Stressor controllability and learned helplessness: The rôles of the dorsal raphe nucleus, serotonin, and corticotropin-releasing factor, Neuroscience and Biobehavioural Reviews, V29, pp 829–84, https://www.uvm.edu/~shammack/Maier%20and%20Watkins%202005%20review.pdf

Murray A (2007) The effects of combining positive and negative reinforcement during training, MA Thesis, University of N Texas, https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc3636/m2/1/high_res_d/thesis.pdf

Palman D (undated) Negative Punishment, Maine Warden Service, https://pawsoflife-org.k9handleracademy.com/Library/Learning/negative_punishment.pdf

Pryor K (2002) The Poisoned Cue: Positive and Negative Discriminative Stimuli, Karen Pryor Clicker Training, http://www.clickertraining.com/node/164

Reisner I and Serpell J (2016). The learning dog: A discussion of training methods in The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behaviour and Interactions with People, pp 211 – 226

Seligman et al (1968) Alleviation of Learned Helplessness in the Dog, Journal of Abnormal Psychology, V73 (3), pp 256-262

Udell MAR and Wynne CDL (2008) A review of domestic dogs’ (Canis familiaris) human-like behaviours: or why behaviour analysts should stop worrying and love their dogs, Journal of Experimental Animal Behaviour, V89(2), pp 247- 261

Vieira de Castro A et al (2020) Does training method matter? Evidence for the negative impact of aversive-based methods on companion dog welfare?, PLoS ONE 15(12): e0225023. https:// doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225023

Ziv G (2017) The effects of using aversive training methods in dogs – A review, Journal of Veterinary Behaviour, V19, pp 50 – 60

Great list – thanks so very much Charlotte! 🙂

I am very surprised that this paper passed the reviewers. Though I have not red the paper, it seems from your description that such a study would be rejected.

Thanks for this blogpost, very intersting and informative to red.

thanks Pia! 🙂

Retraction for conflicts of interest will be an interesting one to watch. CoI statements are declarations made by and about the authors. Per COPE guidelines, a retraction for CoI has to be undisclosed by the authors, and unduly affect interpretations of the work or recommendations by editors and peer reviewers. Ivan is not an author, and is not listed in the mandatory “author contributions” statement. His involvement and expertise are described in the paper itself, and he’s then identified by name in the paper’s acknowledgements (very unusual in a research study). His involvement was not undisclosed to the editors or reviewers – or to readers.

We shall have to see – I’ve never been involved in a retraction process before (though I’ve written two critiques).

Thanks for your incredibly knowledgeable and thorough post. I’m new to the field but not new to scholarly research . I’ve followed publishing ethics (and Retraction Watch) closely for decades and can say this case will be very, very interesting to follow.

I appreciate the long review and I agree with may of your points. On a personal level, I would never consider using an e-collar and I support a force free approach.

Having said that, I strongly disagree with your claim that due to its limitations, the study should never have been published and should now be retracted. Most studies are not perfect – far from it. The authors acknowledged many of the points that you’ve made in their paper. This is one study that looked at one specific comparison, with all of its limitations, and it has value by contributing one more piece of information that we need to consider. Much much worse studies than this are published all the time, and sometimes even evoke a lot of positive interest, because we like their results better. No one ever calls for them to be retracted (even though some of them are much more methodologically flawed and their limitations are not always acknowledged). We can only move forward and promote FF training (or other causes that we may support) by being honest and engaging with the arguments based on the data. And we also need to acknowledge that a lot of people choose to use e-collars or other aversive methods because it looks like a quick and easy fix, whereas FF methods can be much more complicated to apply (which, by the way, also makes it much harder to include properly in a study, since you would need a clear and consistent method that can be replicated by others – it is possible, but you’ve just described yourself how complex this is).

Maybe the best take-home from this study is that comparisons between FF and aversive training should be conducted differently – fair enough. But the data has already been collected – it would be much more helpful for everyone to look at it and understand it, and – indeed, argue about how to interpret it. Calling for it to be buried and ignored does not help anyone.

Hi Dana, thanks for adding your thoughts on this!

Yes, I’ve been very conflicted about this. I think if this were any other paper on any other topic I would absolutely agree with you. The discussion would then stay in academia.

My fear is that the balanced community will take these results and run with it, shouting from the rooftops – and that all our critizism will just be interpreted as whiny and unfounded. And that if we do the other thing we can do, which is publish a formal critique in the same paper, that those papers won’t be linked, and that we will constantly have to tell people who come into the field and see the study for the first time that it’s not good. I often see the “it’s been published, how can it possibly be wrong” stance among people who are not scientists.

But yeah, still conflicted!

There has been strong disagreement about this for a long time. I don’t like to argue the pro’s and con’s of ‘shocking dogs’ anymore. Dogs don’t deserve that kind of treatment any more then people or little children do to learn a lesson. The most most important thing a dog can learn is to come when called by owner. When shock collars are SOLD as some kind of ‘magical communication device’, some inclined (ignorant) people just shock the hell out of poor dog. It is just a fact. ….. they don’t deserve it!!!

Thankyou for this incredibly informative blog – you’ve perfectly put into words what I was thinking/trying to say when discussing this with others.

I did email one of the authors with some of these points. The answers were not enlightening at all (though I didn’t expect them to be, I thought it fair to ask directly rather than just assume).

I honestly think someones lost their marbles, the whole thing is so badly flawed and outrageous its as if its been done by someone with barely more than a high school education!

I actually think that the authors acted in good faith but were duped by the trainer, who fooled them into thinking that he knew what he was talking about.

It’s what I am clinging to… mm!

Sadly I didn’t think so. One of the authors actually mentioned in a blog after he knew many of the issues and failings of the study.

Seems improbable they were unaware of Ivan’s work – he’s high profile and publishes a lot in podcasts, books, blogs, courses, etc.

But even if true, the named authors are fully responsible for the study protocol. That’s a basic rule of academic research, and they would’ve confirmed it at multiple stages through the first author’s doctoral studies (e.g. in the initial proposal, the application to the IACUC, the dissertation approvals), and then again as part of the manuscript submission to “Animals” (the Author contributions statement).

Prof Wynne also confirmed it in a FB post.

Thank you for writing and sharing your review of what Maria calls a “trainwreck of a study”.

As you pointed out it is incredibly flawed and should never have got to the point of publication.

It is really worrying that dog owners not in the know will see this as good evidence to use shock collars on dogs particularly those that have been badly trained to get the the behaviors they want.

Trainwreck is an apt description – you can’t look away!

Thanks Karolina for your thorough review.

25 days between submission and publication is a red flag when it comes to the time it normally takes to get a paper published in a reputable journal. Other peculiarity is the following: “This article belongs to the Special Issue Advancements in Dog Training: Techniques, Welfare and Human–Canine Interactions”. The article is actually doing the opposite and is a setback in dog training techniques, compromises welfare and damages human-canine interactions (to say the least)

I totally agree on the necessity of retraction of this paper.

I’m sharing your blog post in my network.

omg, a special issue! Didn’t realize that – how unfortunate!

I’ve seen comments about this all over social media but hadn’t had the chance to read the paper. Thank you for (as usual) your brilliant and clear assessment of it. Sad to see that such prominent name in the dog world is part of the study, that will carry a disproportionate weight especially amongst pet parents who will have read his book.

Thanks Michelle – and yes, I agree it’s very unfortunate. I feel the authors have been duped by the trainer.

Thank you! I have difficulty reading actual studies due to learning disabilities. This summary is more in depth that the others I’ve read and points out additional flaws with the study. I really hope it’s retracted.

Thanks Cindy!

Seems not. We’ll simply have to point out the bad R+ training as well as point to the fact that the e-collar training was not particularly effective in novel situations – contrary to what’s often being touted.

Thank you for writing and sharing this Karolina

You’re welcome, Cessi! 🙂

Thank you! As I read the study I was flabbergasted. Especially the R+ dogs not being taught which behavior resulted in reward confused me, as well as the delivery of the rewards. My whippet wouldn’t stop chasing something either if I dropped a treat in a bowl 23 meters away while he was already engaged in the chase sequence. Another thing I noticed was the grouping of the dogs: group A has Malinois, German Shepard, Doberman and a single Labrador, overall working dogs with a small action radius and a tendancy to need few repetitions. Group B has more hunting dogs, with high prey drive and a larger action radius and group C has a weird mix of races, many of which are very independent and may not be interested in 120 repetitions. Again, with my own dog I can repeat an exercise about 4-5 times, then he loses interest. Again thank you for your take on that trainwreck of an article 🙂

Hi Maria – and thanks for adding that extra piece to the puzzle! Not being a dog person, I’m not that familiar with the different breeds! 🙂