revised May 2019.

Is the dog fearful, or crouching?

Does it matter, when you’re training?

The world of animal trainers is divided, and I find that some trainers avoid the subject of animal emotions altogether.

“There’s no need to factor in and understand emotions, just deal with the observable behaviour”, is the gist of what some trainers and animal professionals say.

No doubt their unwillingness to consider emotions stems from the Father of Behaviourism, influential to this day. Skinner said: “The ‘emotions’ are excellent examples of the fictional causes to which we commonly attribute behavior”.

I’m not dwelling on what he actually meant by that (…fictional?).

Anyhow, most modern animal trainers don’t question that animals have emotions. It’s just that when it comes to dealing with animals, many tend to address the observable behaviour rather than the emotion that goes with it.

A simplified description of such an approach may be: “if crouching is an undesirable behaviour, let’s make some changes to the environment so that the animal stops crouching.”

And it works, too. I’m not disputing that. At least in some cases – and I’ll get back to when I think that approach completely misses the target.

I’m just compulsive about looking at everything from different angles.

It works – but is there a better way?

Can we improve wellbeing and reduce suffering of animals in our care by factoring in their emotions – on top of being good observers?

I think so.

Taking emotions into account when interacting with animals in our care could:

- Prevent problem behaviour,

- Make it easier to care for them,

- Improve relationships with them, and

- Improve their quality of life

The secret…:

A pinch of anthropomorphism

Anthropomorphism (the attribution of human traits, emotions and intentions to animals) is a word with extremely negative connotations. For many animal professionals, it’s a no-no.

Or better yet, a spice.

Like… cayenne pepper.

Or tabasco.

Overused, it can spoil everything.

And yet – just a pinch can make all the difference.

I don’t like sizzling hot food, so I use very little. Just to bring out the flavors and add that little extra something.

OK, Karolina, very interesting. But how does cayenne relate to animal emotions and anthropomorphism?

A pinch would be the equivalent of thinking: I wonder what situations could cause this animal to be fearful.

Overuse would be comparable to thinking: I’m afraid of snakes – therefore this animal must be too.

Finding the right balance is important. Don’t project your own emotions or intentions on the animal, but observe closely and think “is there an emotional state that could be involved in producing this behaviour?” or even ‘could this situation trigger some important emotional reaction, and if so, is it a desirable emotion or an undersirable one?”

As an applied ethologist working to improve captive animal welfare, I’m biased to especially considering fearful behaviour, foraging behaviour and social behaviour – all related to different core emotional states.

I’ll focus on fearful behaviour in this blog post. In core emotion lingo, the emotion is FEAR, written in caps.

Prediction.

If we take emotional states into account, we can predict where problematic situations might occur. Different species tend to have different reactions when they’re afraid, for instance.

Zebras run.

Monkeys typically climb a tree.

In addition, prey species tend to be more fearful than predators. They’re generally more easily startled, and respond to a wider range of stimuli – different depending on the species.

Armed with this knowledge, we can prepare escape routes: set up the environment so that the animals get the opportunity of doing what they evolved to do when they’re fearful. I discuss and illustrate this in my senior lecturer’s exam lecture, part 2 about ethology, but here are some pointers:

- Give the bunnies hide-outs. Make sure they have two exits, and that every individual has somewhere to go so that there’s no unfriendly rabbit blocking the entrance.

- Provide the zoo-housed zebras with a big corral so that they can obtain a suitable flight distance from all spectators. If they’re spooked, they can have somewhere to run that’s far enough away from the scary object or person.

- Make sure that the monkey exhibit contains many climbing opportunities, so that they can use vertical space. Monkeys usually have strict dominance hierarchies and the highest ranking individuals tend to monopolize the higher levels. For this reason, there need to be enough levels so that even the lowest ranking individuals have the chance of performing the behaviour of jumping up to an empty spot when someone sounds the alarm.

Before you ask: yes. Dominance is a very important mechanism when it comes to monkeys’ social lives. The dominance concept may be severely misunderstood and misused with regards to dog or horse behaviour, but many species, including most monkeys, show distinct dominance hierarchies, especially in captivity.

Ensuring that animals have opportunities of reducing fear by performing species-typical behaviour is key.

Yes, they may get frightened. Such is life. But if they do, they can do something to reduce that fear. They’re in control, as it were.

Animals in control have higher welfare.

Prevention.

One of the reasons why core emotions are so powerful is that they have tremendous survival value.

An animal that doesn’t respond with FEAR to danger will likely not survive long. So, animals need to come prepared to respond fearfully to relevant stimuli.

There are innate fears. Almost all mammals and birds, regardless of species, will respond with a fear reaction to the following triggers – without prior learning:

- Pain

- Sudden movement

- Loud noises

- Certain smells

- Lack of control

- Novelty

In addition to these innate fear triggers, there are learned fears.

The cat learns that the transport box predicts going to the vet to get a shot, which includes exposure to loud noises, novelty, lack of control and pain. The transport box thus predicts innate fear stimuli. A whole bunch of them. Trigger stacking, so to speak.

So kitty starts fearing the transport box.

Is there anything you can do about these fears, innate or learned?

Yes.

Consider what type of stimuli or situations that may occur that could potentially trigger fear reactions, and make sure to teach the animal (through for instance systematic desensitization and counter conditioning) that they’re not harmful – before they even show fearful behaviour.

In other words, by carefully and gradually presenting stimuli that could trigger innate FEAR, you reduce their power as triggers and you eliminate the learned fears that could otherwise be associated with them.

Animals who are not overly fearful have higher welfare.

Problem solving.

Animals who are fearful may show a whole range of behaviour. The fearful crouching dog may tremble, shed hairs, blink, lift a front paw, and so on.

Also, as FEAR escalates, behaviours change. If the animal is cornered, FEAR may switch over into RAGE, another core emotion.

You don’t want that. That’s when things could get dangerous. That’s when animals desperately try to break free using the weapons at their disposal.

By focusing your attention on the emotional state rather than on individual responses that may or may not be shown for any length of time, you can cut to the core of the problem.

By helping the animal change his emotional state, you will change the behavioural manifestations too.

Let me re-phrase that sentence, because it carries some extremely important implications.

When emotions change, so does behaviour.

Behaviour can change, not because the animal learned something, but because emotions changed.

See what I’m getting at?

I’m getting at the fact that people may be fooled to think the animal has learned something, when in fact, all that has happened is that the animal has changed emotions, for instance, by becoming fearful.

This is one of the main problems with punishment as a learning tool.

Say that the dog pulls on the leash. The owner punishes the dog, say, by kicking him and saying “tsssst!” as some dog trainers on TV advocate. The dog stops pulling, and the owner thinks it’s because he’s learned that pulling leads to unpleasant consequences.

That may be so. The owner will likely find out on the next walk.

Or, it could simply be that the dog is now frightened and no longer in that SEEKING mode (another core emotion!) that lead him to pull in the first place.

That’s a double whammy, by the way.

SEEKING is a wonderful feeling, FEAR sucks.

The problem with FEAR is that as arousal escalates, learning goes out the window. The animal may stop responding to known cues, become frantic – or flip into RAGE.

It’s vital to recognize when there’s a FEAR component in a behavioural problem.

Problem solving is facilitated by considering emotional states.

Precision (nerd warning).

Skip this part if you’re not a training nerd.

Still here? Well, I did warn you.

Ever wonder why a VR2 is the optimal Variable Ratio Schedule to keep an animal engaged? In other words, delivering a reinforcer on average on every second response?

Because that ratio essentially implies the maximum amount of unpredictability. There’s 50% chance of getting a reward, and 50% of not getting one. That’s as unsure as it can get.

That type of unpredictability of appetitive stimuli completely hijacks the dopamine system involved in the SEEKING response, that other core emotion. Professor Robert Sapolsky talks about this in this brilliant TED talk – start looking at 26.30 and keep going for about 5 minutes. Then try to stop watching.

If I were a dude, I’d want a beard like that.

Woops. This was going to be about FEAR, not SEEKING. Or beards.

Sorry for deviating, I’ll get back to the subject.

Priorities.

One of the tenets of captive animal husbandry is to allow animals to express species-typical behaviour.

Animals in the wild show an enormous number of different behaviours, easily numbering the thousands if detailed.

How do we prioritize? Which of all those are important?

I would argue that behaviours associated with core emotions are important. Core emotions are tightly linked to behaviours necessary for survival and reproduction.

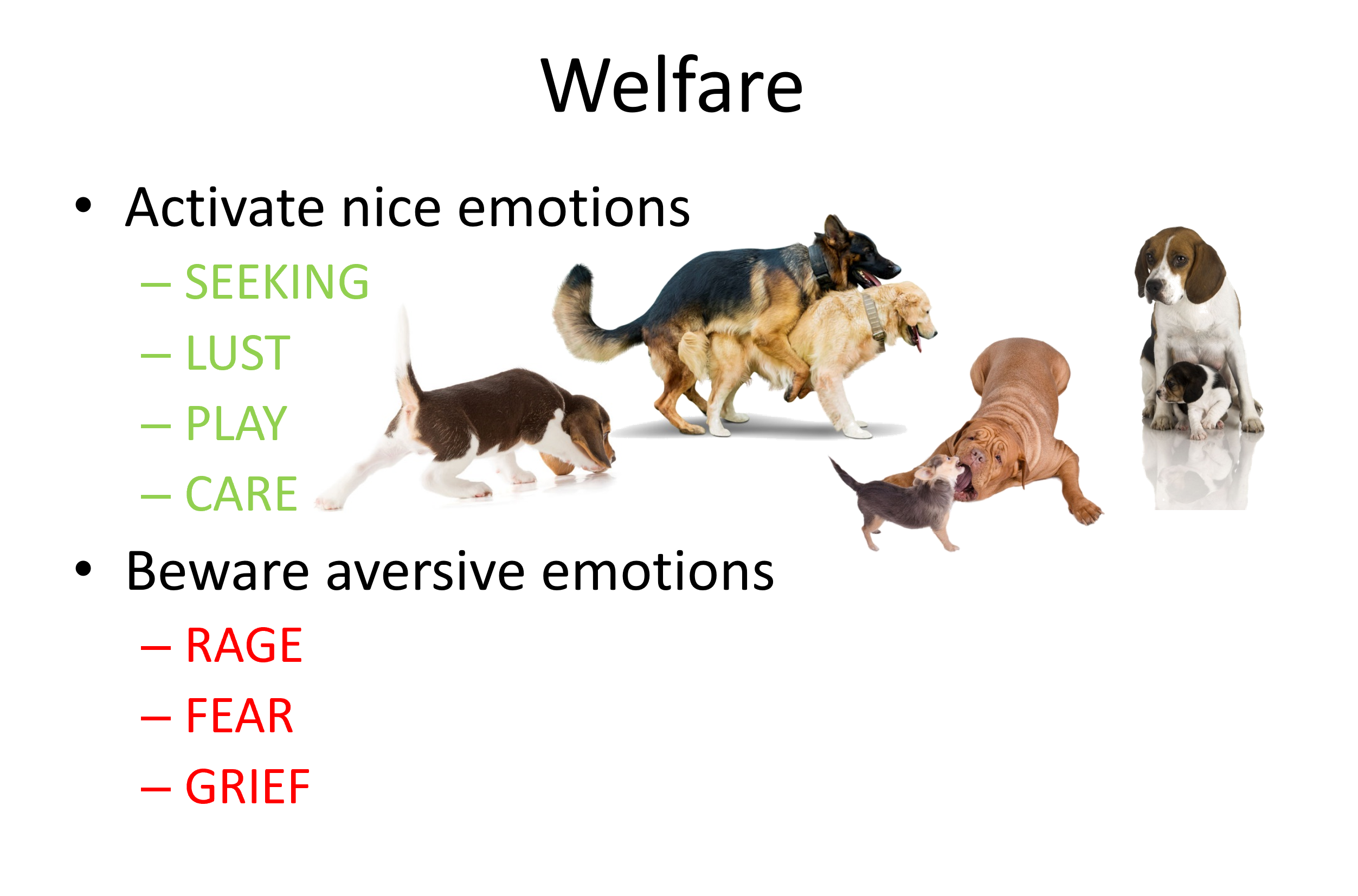

Which are the core emotions, then?

Well, renowned affective neuroscientist Jaak Panksepp has identified seven of them (and he writes them all in caps). Four of them lead to improved welfare, and three of them may have negative impact on the animal’s long-term health.

Perils.

What are the risks of addressing emotions rather than behaviour?

By assigning an emotional state, we move away from observing and start interpreting. The main risk (among several) in doing so is that of misinterpretation.

Don’t lose track of what the animal is actually doing. It takes a keen experienced observer to know the emotional state associated with a specific behaviour for a particular species. For this reason, it’s often a good idea to keep track of actual behaviours (crouching, ears back, large pupils, wide eyes, weight distribution) in addition to the probable core emotional state – and of course, the context in which they occur, and whether they diminish or intensify as a result of changes in the environment.

Why addressing observable behaviour isn’t enough

Getting back to why I think it’s not enough to just look at observable behaviour – to me it’s problematic in several ways:

- When prioritizing, we may focus our efforts on observable behaviour that is troublesome to us (such as a barking dog), even though the situation may be troublesome to the animal (for instance, the dog may be quiet but still very uncomfortable).

- We don’t realize the importance of certain core emotional states (SEEKING and PLAY, for instance) with regards to brain development, personality, stress coping abilities and social competence – and even stifle them.

- We may fail to notice subtle behavioural signs; the early indicators of unease, unless we’re specifically looking for them.

Conclusion.

It is my firm belief that as trainers we can be inspired by different scientific disciplines – and the field of emotions is one of them.

By taking core emotions in animals into consideration, animal trainers may better predict responses, prevent undesirable behaviours, problem solve more efficiently, increase precision in their training, and prioritize more effectively.

Oh, and about that leash pulling – what to do then, if punishment is out of the question? I cover that here.

***

I teach about all aspects of behaviour management – and my online courses are wildly popular. They’re only available occasionally, though – sign up and I’ll notify you! You’ll also learn whenever I offer a free webinar, masterclass – or publish a new blog post.

Panksepp (1998). Affective neuroscience: The foundations of human and animal emotions.

Skinner (1965). Science and human behavior.

Wow, to the blog as a whole and the TED-talk! Impossible to stop watching!

I have come from working with small animals for years as a veterinarian. I wish had had more of these insights during many of those encounters over the years. Often time was limited but I got to know some animals with frequent visits. Certainly many were fearful and some fed off the anxiety of their owners I think. Getting the owners to relax and let go of the animal was often my first task.

Things have changed a LOT in the veterinary industry in the last decade or so… hopefully these are ideas that are actually taught in vet school today!

One of the primary reasons I love sharing my life with animals is because they exhibit emotions that I can both relate and respond to, making our relationships more interactive and alive

❤️

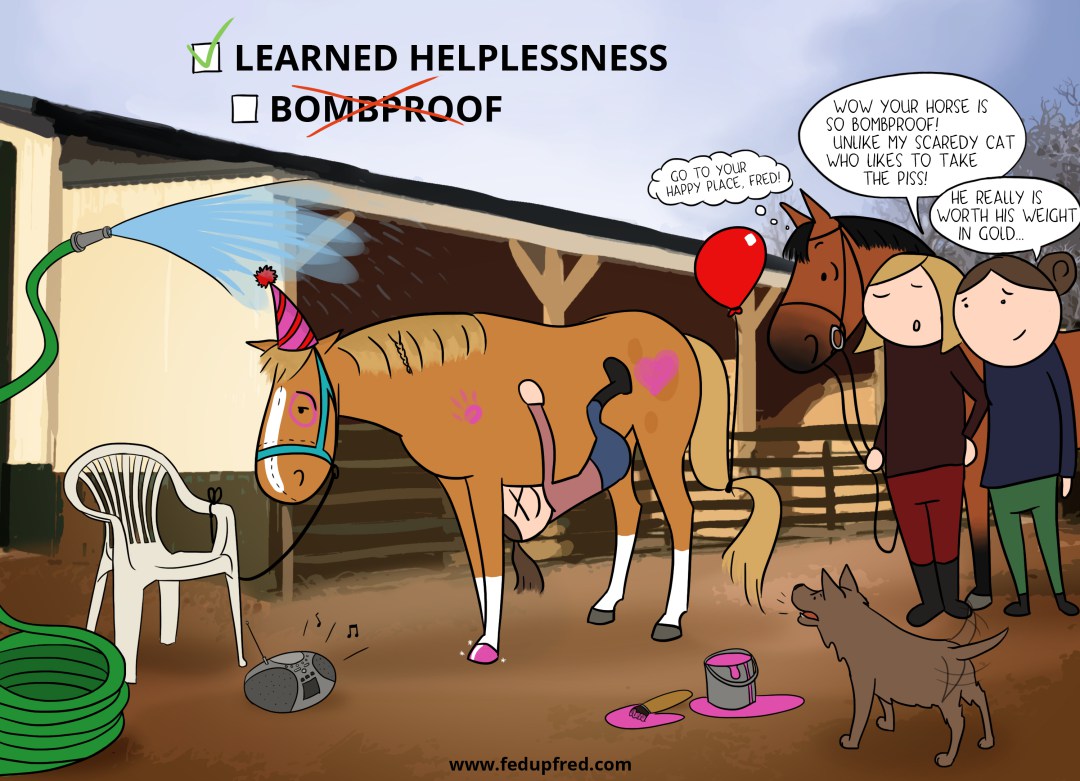

My mind is blown every time I read a new chapter. As a horse trainer, I learned a long time ago about learned helplessness but was always encouraged to avoid anthropomorphisms. What a light bulb moment you have triggered with quite a few cases I have dealt with in the past!

I have also read the blog on dogs pulling on the lead and never considered the debate regarding a standard collar. I’m now going to go and buy a correctly fitted harness today!

Hi Bev – so glad that these posts resonated with you! 🙂 Best of luck with the harness! 🙂

Wow things in here keep giving me a new discomfort to deal with. I practically preached to people how terrible anthropomorphism is. However I did seem to do it correctly. It’s mostly when people apply it too much that I tell them how bad it can be to do so. But I have always told people how important an animals emotional state is in every situation. Of course animals have emotions. We CAN observe them in real time. Because every behavior has an emotion attached to it. What a wonderful way of being able to tell clients the importance of taking their animals emotions into consideration. It’s about how THEY feel, not how we assume they feel. I often see pictures of animals wearing sweaters and people will caption “my dog just loves wearing their sweater!” But in The picture the animal doesn’t necessarily scream the emotion of enjoyment. The general pet owner anthropomorphizes these types of things so much. I’m not sure I would use the term “a pinch of anthropomorphism” so much as just explaining that we should take our animals emotions into consideration and think about how they may feel in a situation. Many of the terms used have unfortunately been poisoned and leave a bad taste in the mouth when trying to explain it to people that aren’t trainers but just regular pet owners. I don’t want anyone to misinterpret or misunderstand what I’m trying to say. I tend to avoid using any words I think they may take and run with. The important thing is that I agree with this entirely and I understand what it’s saying. Using “a pinch of anthropomorphism” to better understand how our animals feel can absolutely help us to make sense of a situation, prevent negative outcomes and set our animals up for success! The five P’s is a wonderful set to come back to in every session. An animals emotional state should always be the first thing considered.

It can be terrible, for sure – but I think it’s been unnecessarily vilified..! 😉

I have several emotionally sensitive dogs. I like thinking about what is triggering their issues, so i can help them.

This does not help with what I wanted to try and understand. “Don’t question that animals have emotions?” I want to learn about it. What even is the point of this then? The way these people worded it is very, VERY, confusing. I hope you can get back to editing this. Not the best site, but decent in my opinion.

Unlike Shigure-nii, (sorry about his attitude toward the editing) I think this really helped with my life. I have three dogs, one who is struggling with getting yet ANOTHER puppy. I’m just watching her, and I’m thinking, “Wow, this dog is struggling.” I just feel a ping of guilt in this. Thank you so much for helping me deal with my dogs emotions.

-Kiri (Kiki)

Thanks Kiri – glad you found it useful! 🙂

Hi Shigure-nii, sorry this post didn’t resonate with you..! I talk a lot about how emotions influence behaviour, and what to do about it, elsewhere – not just in this post. 🙂

I am glad I found this article. I train service dogs and horses. I have been so successful until now. I have a horse, a dog and a cat that are very emotional and I am struggling. That cartoon brings TEARS to my eyes. That is this horse. I have worked with several trainers and I get behaviors but he still is in the state of learned helplessness. It breaks my heart. I would love to learn more about your program.

The dog was a super confident dog until she had emergency surgery and almost died. I was away for work and I came home to this terrified girl. I have tried all the things but she kinda presents like she internalizes at some requests on some days and anytime else I see the dog I specifically picked out as a puppy.

The cat is a rescue that I have no idea what happened. I have created a trust relationship but I can’t seem to help her loose that “scaredy cat” behavior to the other cats. I would LOVE to help her free herself of that burden.

I would love to help all of them loose that burden.

I would love to hear from you.

Thanks

Stephanie, thanks for sharing your story! It can be heartbreaking for sure when we don’t know how to help our furry friends. Hopefully you can find some insights in some of my other blog posts and trainings..! I know lots of people are using Nose Work with their insecure dogs to great effect – not much research done yet, but anecdotally I hear really good things, perhaps worth exploring?

A really useful article- in my studies of body language it was stated tome & time again to look at only observable signals & avoid interpreting these as how the animal might be feeling. I understand why i was being told this but i think i may have taken from it that trying to interpret how the animal is feeling is something we’re better off avoiding as much as we can (always!).

I think this blog has allowed me to really understand that the times where i do actually interpret the body language signals and label the animal with having particular emotional states etc is not a lapse but rather something that is appropriate at that particular time.

And of course in dealing with dog owners as clients alot of what we’re trying to do is give them the opportunity to empathise with their dog in different situations by helping them read body language signals in order to understand their dogs emotional state! Its only the behaviour geeks of us that actually want to list observable signals in isolation to block out the tendency to interpret when that may cloud what we’re trying to see or understand in the animals behaviour !

Great point. I truly believe it depends on the hat you’re wearing whether the main focus is on observable behaviour or on emotional states. Both perspectives have their merits, for sure! 🙂

Pulling on the leash is often a big problem for dog owners. You write in the blog post “The owner punishes the dog, say, by kicking him and saying “tsssst!” as some dog trainers on TV advocate.” I agree this seems wrong. However, how can you instead solve the problem with pulling on the leash? I would be very interesed to hear your opinion which does not appear in the text.

I cover that here! I’ll make sure to link to that page! 🙂

https://illis.se/en/on-the-danger-of-dog-collars/

Hi Everybody, so interesting. Thank you very much. Kind regards

So interesting! You confirm my intuition about animal emotions and help me develop my training ractices.

I was at a horse clicker training clinic last year. The clinician was a former marine mammal trainer with decades of positive reinforcement experience. She had said that changing behaviour is easy, changing emotion is the difficulty. So glad to be in this course actively considering and learning the impact of emotion. Your example of learning vs change in emotional state Was insightful for me!

Glad to hear that you found it useful! 🙂

Hi, I’ve really enjoyed the introduction! Lots to say but I’ll let it ferment till I have learned a bit more. Thank you!

Glad to hear that! .-)

This was very helpful, I have always explained to clients that while in a state of fear or over arousal their dog cannot respond, it is not that they are being disobedient. I liken it to asking someone to stop having goosebumps because they are cold, it doesnt matter if you offer something good, punish them, shout at them louder they cannot change a physiological responce to cold. What we can do is prevent them getting cold in the first place, or build up their tolerance to the cold gradually.

I also didn’t know VR2 was the best ratio for reward, I thought it just had to be unpredictable. When shaping behaviour I often will ‘jackpot’ when I get the final behaviour I was looking for rather than an increment, as a clear indicator of ‘that’s what I was looking for, keep doing this’, is there a better way?

The goosebump example was great! About VR2s, it’s simply the ratio where there’s the most unpredictability, not necessarily the best.

Jackpots are tricky in that they can be overused – most people use them for significant breakthroughs, not just achieving what the trainer decided is the final behaviour..!

LOVE the goosebumps analogy. I’ve often heard analogies based on human phobias, but this purely physiological comparator is genius!

I love the ‘pinch of anthropomorphism’! So far I have struggled to explain that whilst dogs experience some emotions like fear, they don’t experience guilt for instance. My clients sometimes look at me in disbelief as if I am making it up! I also find the idea of changing an emotion to change or modify a behaviour extremely useful!

🙂 At least, what people most often interpret as guilt, seems more commonly fear-related… brought on by a punishment history in that context.

I am so glad to read this. I really like the “a pinch of anthropomorphism” section. The way that you are explaining makes so much sense to me. I have struggled in the horse world dealing with trainers who continually told me not to anthropomorphize my horse. I would get so upset because I have always taken his emotions into consideration. How could I not when I see them clearly. This is so refreshing!

Thank you, I’m really glad you found this useful! 🙂

Thank you for sharing