(revised Jan. 2019)

Is your dog or cat offered treats during the visit to the veterinarian?

I can think of two reasons why this might not happen.

- The vet is unfamiliar with how extremely useful treat feeding is in preventing, reducing and eliminating fear in the veterinary clinic. After all, it’s typically not something they learn in vet school (although thanks to organizations like Fear Free, that’s now rapidly changing!)

- The vet doesn’t dare feed treats in case the animal needs to be sedated, thinking that “animals need fasting before sedation”.

For several years, I’ve been teaching about fear, anxiety and stress (FAS) in pets during veterinary visits. Among several topics, I’ve spoken about why treat feeding is such a powerful technique to reduce and eliminate – and prevent – fear and fear learning. This is called counterconditioning.

But in the various groups of veterinarians and vet technicians I’ve lectured to over the years, I’ve kept hearing the same objections over and over again:

“That sounds great”, the vets would say. “But if we need to sedate them, we can’t feed them so soon before we put them under”.

That got me curious, and I started asking questions:

- How soon before sedation can we feed, then?

- What if you just feed a teeny weeny little tidbit?

- How about broth – liquids surely must have really short gut passage time?

- How big is the increase in risk if you do feed before sedating?

- How dangerous are the complications, anyhow – would the benefits be worth the risk?

As a scientist, my knee-jerk reaction was to look for the article that addressed those questions.

I didn’t find one. There wasn’t any. Nobody had looked at that!

For me, it was really frustrating to realize that treat feeding at the vets was often avoided based on some notion that it might be dangerous – but that notion wasn’t based on any solid data: the risks hadn’t been properly examined and discussed.

Two treatments: feeding treats versus not feeding treats.

Essentially, the veterinarians I met (and yours too?) were avoiding feeding treats during vet visits because they considered it a “treatment” with allegedly dangerous side effects if for some reason the animal had to be sedated. So they would choose not to use treats and counterconditioning. That’s problematic if those fears turn out to be unfounded (hint hint: they sure seem to be).

And they didn’t seem to realize that not feeding treats at the vet’s is also a choice, albeit a passive one – it’s also a “treatment” with potentially huge unwanted side effects! Only these side effects are well documented, and involve increased levels of distress, risk of defensive aggression, potential difficulties in diagnosis, unhappy owners and risk of injury to everyone involved in restraining the stressed-out animal. That’s highly problematic too, and paraphrasing veterinarian Karen Overall on the failure to recognize that FAS (fear, anxiety and stress, remember) in pets during the vet visit should be a major concern in veterinary medicine: “We’re causing severe irreversible damage in the way we’re handling them.”

The veterinarians I was speaking to were facing a choice between two rather terrible options, or so it would seem.

- On the one hand: successful counterconditioning – contented animals that, according to general consensus (but with no apparent scientific support) risk dying from complications associated with anesthesia because they’ve eaten minutes before being sedated.

- On the other hand: miserable and potentially dangerous animals that run no particular increased risk when sedated (… actually, my findings challenge that assumption, as we will see below).

Talk about catch 22 – neither option is particularly enticing!

But – were those the real choices? Is there truly a catch 22, here?

And, would it be possible to get the benefit of the treat “treatment” – but without the risk of side effects? A happy animal that doesn’t run any increased risks when sedated?

Well, I don’t know about you, but me, when faced with an intriguing question like that, I tend to dig in and do some some research.

This time, I ended up publishing a scientific paper in the Journal of Veterinary Behaviour.

Relevant findings about gut content, regurgitation and aspiration pneumonia

I plowed through every study I could find on risks associated with feeding and sedation. Most studies are on dogs or people, by the way. And yes, the complications related to sedation are potentially extremely dangerous, even lethal.

Surprisingly, I found nothing in the scientific literature supporting the decision to stay away from treats – I could even argue the opposite: it might be more risky not to use counterconditioning before sedation (and through no less than three mechanisms). Sedation is always a risk, but there’s nothing to indicate that it would be riskier to countercondition the animal using small amounts of treats even close to the moment of sedation – if you do it right.

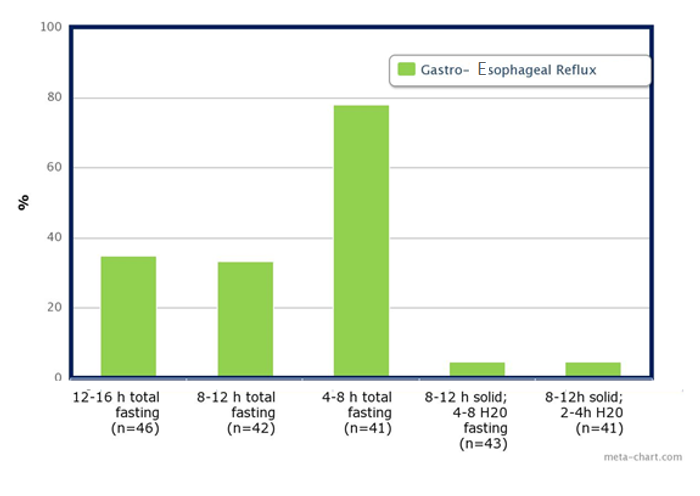

According to the diagram above, there is no apparent relationship between how long the animal has fasted and how big the risk of GER is. Indeed, the lowest risk of GER is seen in dogs who have received water up to 2 hours before anesthesia. Note that this study didn’t cover any treatment involving fluids or small food amounts offered right up to the moment of sedation, so we lack data on that interval.

Still, if the animal regurgitates, things could get really serious if gut content ends up in the lungs – Aspiration Pneumonia (AP) could set in.

Also, the risk of AP correlates with how much content is in the stomach at the time of regurgitation, so the major issue is not when the animal last ate, but how much is in the stomach.

Now, you may think that there’s a correlation between those two – “if the animal ate recently, he must have more food in the stomach” – but when the animal last ate is not at all as important as what the animal ate.

Also, when the animal last ate is not as important as has there been any recent gut motility?

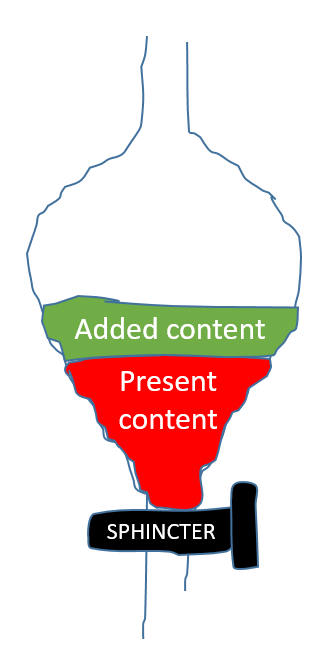

Stomach content volume depends both on how much was in the stomach to begin with, how much is added, and what is going on at the lower end – is the sphincter releasing stomach contents to the intestines?

It turns out that if you’re not treat feeding or doing other forms of low-stress handling, most animals (about 80% in dogs) get stressed at the vet’s. One of the most well documented effects of stress is that it inhibits gut motility, so whatever was in the stomach is likely to stay in the stomach if the animal is stressed.

In contrast, if you’re successfully counterconditioning, gut motility should be up and running. If you’re feeding small, fluid amounts and keeping fear, anxiety and stress at bay, it could be that the stomach is actually emptying faster than it’s being filled.

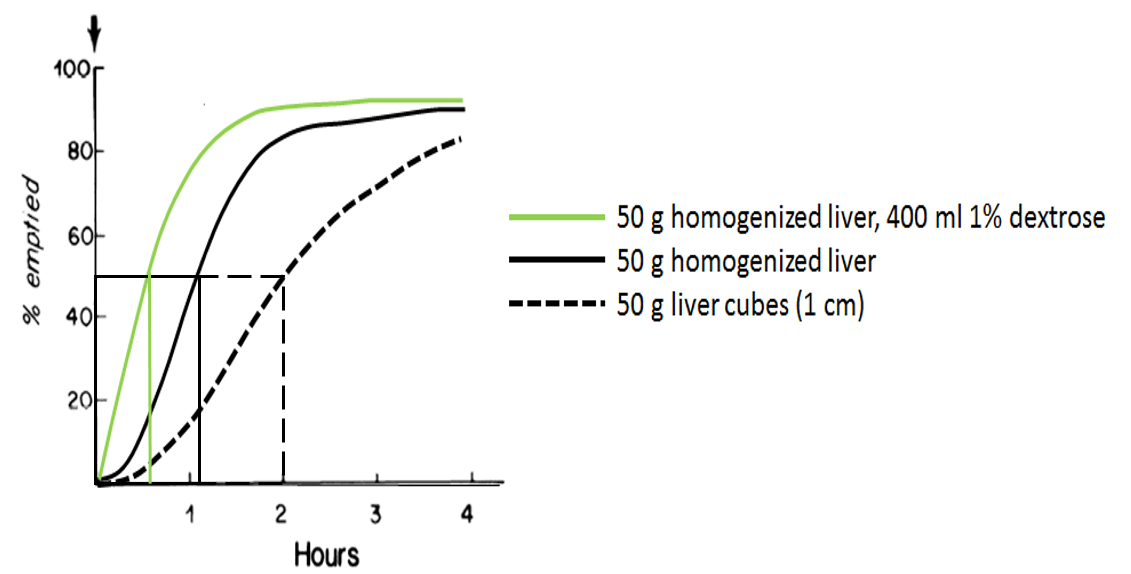

As mentioned, the choice of treats will impact how quick the gut passage is. Half the content may be emptied in 2 hours, just over one hour or in about half an hour depending on whether a dog has been fed liver cubes, homogenized liver or a rather large suspension of homogenized liver.

So, if we need to minimize the stomach content volume before sedation occurs, we should choose liquid or fluid treats, that pass through the gut more quickly than solids. We should also ensure that the animal isn’t stressed, and incidentally one of the most reliable ways of doing that is by strategically feeding the animal – counterconditioning.

This study also revealed that a huge factor in the risk of AP in sedated dogs has to do with the choice of sedative – which drug is used to put the animal to sleep. Some are emetic (causes vomiting), and some are not. If possible (and sometimes maybe it’s not), ask your vet to choose a non-emetic option.

My conclusion is that there are mostly disadvantages with not feeding treats, and mostly advantages with doing so.

So, to summarize: if you’re using small amounts of a fluid treat to reduce fear in the veterinary clinic, there is no reason to assume that there is an increased risk of Aspiration Pneumonia (AP) if the animal needs to be sedated. Potentially, the opposite is true: if you don’t address fear, there might be an increased risk of AP.

There is no catch 22 in this scenario.

There is no reason why vets shouldn’t use treat feeding to countercondition animals during the vet visit, reducing FAS – that’s fear, anxiety and stress, but you know that by now, don’t you? 😉

In fact, I can think of four reasons why veterinarians should ensure that, unless medically contraindicated, animals should be offered treats during a vet visit. Treat feeding will not solve all problems in the veterinary clinic, but is one powerful tool in the toolbox of prevention, planning and low-stress handling techniques available. In my opinion, treat feeding should be the norm rather than the exception in the vet clinic.

If you’re interested in getting a copy of the scientific paper I wrote, just click the hyperlink below to send me an email request (I’m not allowed to share it publicly, but I can send it privately).

… I realize this line of reasoning is hypothetical, at this point. No-one has examined effects of counterconditioning using treats on the risk of Aspiration Pneumonia – AP. What are your thoughts? Leave a comment below!

***

I teach about behaviour management – if you’re interested in learning more, sign up to get info about future blog posts, free webinars, silly experiments and online courses:

References:

Hinder & Kelly, 1977. Canine gastric emptying of solids and liquids.

Shiun et al. 2006. Preoperative fasting in dogs.

Westlund, 2015. To feed or not to feed – counterconditioning in the veterinary clinic.

14 replies on “Why vets shouldn’t avoid treat feeding in the clinic”

I’ve mostly worked with horses, but as a vet-student I worked at a small animal hospital. I was never taught the fasting because of huge risk during sedation/anaestesia, but because the cat or dog often get nauseous and throws up. The more (solid) food in the stomach, the worse the animal in general gets – and they really do look awful!

There is a potential risk of regurgitation when the animal is under anaesthesia, but I’ve never seen it – and I’ve never heard an experienced vet be nervous about it.

……. but I’ve seen animals get less confident at the vet after they’ve puked hard – so I do find it valid to give less treats before surgery and fast at home. But have pockets full of treats the rest of the time 😉

Horses “cannot” throw up. Anatomically it’s because of how the stomach and eosophagus is connected; when the stomach fills up it will close off to the eosophagus(yes, a bursting stomach is a real concern with colic horses!).

We don’t know if horses get nauseous, but I’ve never seen problems with horses who got lots of treats before sedation. Only problem is if you are to examine the teeth and they are stuck with treats – flushing carrots, grass or hay out is okay, but the treats from the stores, jeeeesh, that can take 1/3 of your good sedation time!

interesting – thanks for sharing! <3

[…] often avoid treat feeding during consultations because they fear Aspiration Pneumonia if they need to sedate the animal. Hypothetically, there could be an increased risk of Aspiration […]

[…] assortment of fabulous treats, in order to bring about this important learning. And there’s no scientific support for the old adage “the animal must fast before sedation, so we can’t feed treats in case we need to sedate the animal” – in fact, it […]

Hi!

As a horse owner I wonder if there is a AP risk at all. As long as the treats come before the shot, there shouldn’t be a problem, right.

I’ve got to ask my vet about this, he did get quite upset when I started feeding treats to make sticking the needle in my horse a bit more easy for her (we have done training with needles and candy before the vet visits).

Interesting anyway!

I haven’t seen AP described as a problem in horses – nor does it seem to be in cats. I’m not a vet, through…

I think for horses there could be an immediate hazard (of maybe rather fear of hazard) of treats getting stuck, but the vet could just wait with injecting the solution until the horse has swallowed.

I am very blessed to have vets that keep a freezer full of bowls with a thin layer of peanut butter spread inside as well as peanut butter covered spoons. The small amount of peanut butter takes a long time to lick off by the dogs building a positive association with the vet and the clinic. My dog into the clinic to have fun with their vet friends.

Interesting that we all love peanut butter, no matter the species. Thinking about nut allergies, though?

Hi!

I wanted to read the whole paper “Shiun et al. 2006. Preoperative fasting in dogs.”

But when I search pubmed and google I can not find it, can you help me and direct me to it?

Kind regards

That was a tricky one, I couldn’t find it first either so I wondered if I had quoted it correctly. But here it is:

http://www.veterinaria.org/revistas/recvet/n010106/050106b.pdf

Your arguments are sufficiently compelling that somebody should do a study and collect data. That’s the only way to really find out. It seems worth it!

I’m still getting the “better safe than sorry” type answer. I’m thinking one easy start would be just to score the fear level of the animal at sedation and once you have a couple of thousand sedations see whether there is a correlation between fear level and the risk of AP. I don’t think anyone dares do the actual experiment of giving treats to dogs before sedation – at least not with privately owned dogs. And since the incidence of AP is so low, that’s the only way I think – the sample sizes need to be vast, so a laboratory experiment is out.

[…] to what many vets have assumed, there’s no evidence to indicate that it should be riskier to feed treats with the purpose of reducing fear in animals about to undergo sedation. There may be other reasons […]