Updated June 2024

I finally finished reading a book.

It took me three years to read.

Three.

Years.

And it’s not because I’m a slow reader. I plowed through Brandon Sanderson’s 1100-page brick The Way of Kings in less than a day. So why, then, did this particular book take me so long?

Well, before I tell you, let me frame the context.

It’s a book that’s getting a lot of traction amongst animal trainers lately, specifically amongst the behaviour analytic crowd.

The book is called How Emotions Are Made, and it’s by Lisa Feldman Barrett, a professor of Psychology and a neuroscientist. In the book she makes a big, and in many peoples’ eyes, compelling, case of emotions being constructed rather than innate.

So, many behaviour analysts love the book, and I feel like a complete dissenter in that crowd, because while they’re all nodding in agreement, I shake my head thinking that some of the main conclusions in the book are seriously flawed.

We’ll get to my objections in a minute, but let’s start with: what is the central idea behind the Constructed Theory of Emotions?

What the Constructed Theory of Emotions (CToE) is all about.

The case Barrett makes is that rather than being innate, emotions are constructed.

According to the CToE, emotions are not our reactions to the world, they are our constructions of the world. The theory suggests that our past experiences guide us in making sense of incoming stimuli, and emotions would then be actively constructed from sensory input, previous learning, and language.

In the book, Barrett goes on a quest looking for what she refers to as “fingerprints of emotions”; looking for evidence that humans would have innate facial expressions indicating different emotional states, or that these different emotional states would be processed in specific parts of the brain; in a “fear center” or an “anger center”, for instance.

Her conclusion is that we do not have innate facial expressions related to emotions, but rather, we learned for instance to smile when happy by watching others do it, and she also rejects the notion that categories of emotion such as sadness, fear or anger would take place in a distinct brain location, or brain blobs, as she jokingly calls it, but rather she leans on a body of research that proposes that each instance of emotion is a whole-brain state; emotional processing taking place throughout the whole brain at once.

She rejects what she refers to as the “classic” view of emotions being innate.

“Human beings are not at the mercy of mythical emotion circuits buried deep within animalistic parts of our highly evolved brain: we are architects of our own experience”.(p 40)

Human infants don’t feel emotions, according to Barrett, because they lack the rich set of concepts required to construct them. They do feel affect, though: pleasant or unpleasant sensations, but not fear, sadness or joy.

Barrett also suggests that if someone doesn’t have a concept to describe an emotion, they won’t be able to perceive it. They might still feel the bodily sensations associated with the experience, but won’t be able to label them precisely.

In other words, according to the CToE, the range of emotions a person can experience is limited by their emotional granularity – the ability to construct and identify more precise emotional experiences. And language is crucial here – without language, there would be simply pleasant or unpleasant feelings (affect), and specific emotions concepts are not constructed until we start labelling them, using language. According to Barrett, a person with low emotional granularity may experience a stomachache in a particular situation, in contrast to a person with a more granular emotional vocabulary, who might experience anger in the same context.

That is, animals don’t experience emotions, according to the CToE: they simply feel affect. Since they lack language, they can’t categorize emotions, and they go through the world experiencing pleasant and unpleasant situations, and reacting with different degrees of arousal – but not emotions as such. No fear, anger, sadness, joy.

The reason why we think animals feel emotions, according to the CToE, is because we feel emotions, and we anthropomorphize and project. To paraphrase Lisa Feldman Barrett, humans might perceive a dog crouching with ears back and lip licking as fearful, when in fact all he’s feeling is an unpleasant experience, not “fear”.

Barrett suggests that we think animals have emotions because we make the mental inference fallacy: we unknowingly apply our own emotion concepts to the behaviours we observe in the animal, and we wrongly attribute emotions to those behaviours.

“Construction views of emotion are frequently misinterpreted as saying “dogs don’t have emotions”[…] Such simplistic statements are meaningless because they assume emotions have essences so that they can exist, or not, independent of any perceiver. But emotions are perceptions, and every perception requires a perceiver. And therefore every question about an instance of emotion must be asked from a particular point of view.” (p 272)

So, in Barrett’s view, emotions are the concepts we make up when we think about how we feel in situations characterized by some type of affect – but those affects themselves are just somewhere on the scale from pleasant to unpleasant, or characterized by a certain degree of arousal. There’s no such “thing” as fear, rage or happiness, neither for humans, nor for animals.

This, in short, is my understanding of the central themes of the book and the conclusions relevant for those of us interested in animal behaviour and welfare.

And I have major problems with these conclusions. In fact, when first reading the book, I finished chapter 1 and thought “this is clearly wrong”, and so I put the book aside, waiting for someone to debunk it – so that I wouldn’t have to.

And then I waited a couple of years, but I never came across any such critique – and yet I see parts of the world of animal training accepting the teachings of the CToE as absolute and irrefutable; I’ve even attended a conference where a leading Behaviour Analyst suggested that we throw out all our old literature on emotion from our bookshelves, more or less hailing the CToE as the new gospel.

So, since there seems to be no critique forthcoming, I finally bit the bullet and sat down to read the book – so that I could write one, at long last.

I chose to write it in blog form rather than a formal scientific paper, because then a) I don’t have to provide academic references for every other statement, and b) I can easily edit and revise any of the no doubt numerous mistakes and misinterpretations I’m about to make.

So, fair warning: this blog post may evolve as my understanding of these concepts change.

After all, that’s what science is all about. Trying to make sense of the world through observation, experiment and civil discussion – and our scientific ideas and theories changing over time as we learn more.

One reason I suspect that there will be revisions of this blog post is that I’m no neuroscientist or statistician. A lot of the information in the book is simply beyond my area of expertise, and I don’t know enough about the subject matter to assess whether experiments were well executed and actually measured what they claimed to measure.

But those shortcomings won’t stop me from writing this post, because I do feel confident and competent enough to raise objections to the CToE from one particular area, and that is the evolutionary perspective. Being an associate professor of ethology, I’m on reasonably solid ground here.

And from the evolutionary perspective, the Constructed Theory of Emotions is plain wrong.

And here’s why.

The evolutionary perspective.

Whenever we come up with a theory that might explain behavioural or morphological traits in humans or other animals, we must start by doing a quick check whether it makes sense from an evolutionary perspective.

Sort of like a litmus test. Does our new theory make sense? If yes, then we can move on and try to figure out the details.

If the novel theory doesn’t make sense from the evolutionary perspective, then we need to throw it out and start over.

And let’s be clear: everything in biology must make sense from an evolutionary perspective. Unless we’re counting on divine intervention or extraterrestrials to have played any role in how the human condition came about, our biological world, and humans within it, evolved under the unforgiving rule of natural selection.

Generally speaking, only the best adapted individuals survive, over time.

Typically, one way that we evolutionary biologists tackle this topic is by asking a very simple question.

“Would someone with this trait do better, or worse, than someone without this trait?”

In this particular case the question would be: “would someone who constructed emotions do better, or worse, than someone who didn’t construct emotions?”, or perhaps rather “would someone who constructed emotions do better, or worse, than someone who had innate emotions?”

Which strategy is the most effective?

To answer that question, let’s do a little thought experiment.

Let’s say we live in a group of pre-historic humans.

And let’s say that, within this hypothetical group, there are, thanks to some random mutations, two main strategies with regards to emotions: a number of individuals who have the strategy of Innate Emotions, such as fear, anger, sadness etc. And one subset of the group has the strategy of Constructed Emotions: they learn through experience what to do and how to name the affects they experience in different contexts.

Now, imagine belonging to the second group, and you’re standing there on the savannah, digging for some yummy roots, and all of a sudden there’s a pre-historic big cat with huge fangs rushing towards you.

The theory of constructed emotions would then suggest that you may experience an unpleasant reaction, and perhaps get increased arousal… and then what?

Without any previous experiences of being ran at by huge-fanged cats, the theory suggests that you experiment to see what works best, and learn from your actions. Perhaps try running. Perhaps try yawning. Perhaps freezing in place, immobile. Perhaps keep digging.

A thousand options. Take your pick.

And the outcomes of those options will be decided by trial and error. Sometimes you choose a good option, and succeed.

Only, and here’s the problem, in some situations, such as when a big fanged cat is sprinting towards you, the errors will get you killed. Out of the four behaviours I listed, only one is likely to lead to survival in this context – running.

But let’s say there’s another human in that pre-historic group, one that has a propensity of showing innate emotional responses, such as running-in-the-face-of-danger. Another strategy.

So, whenever that person sees a big kitty rushing towards him, he’ll get not just an unpleasant feeling, but a fear reaction, and start running. Or show another behaviour that’s part of the cluster of fear-related behaviours.

And so, the person-who-shows-fear-related-behaviours-such-as-running-from-cats is much more likely to survive a random cat attack than the person-who-experiments-and-learns-from-trial-and-error.

And in the next generation, the genes from the one-who-runs-from-cats will be more prevalent than the genes from the one-who-experiments.

Until finally, the one-who-experiments has gone extinct.

This is natural selection at work.

And that’s why I first stopped reading the book How Emotions Are Made after the first chapter, because the theory of constructed emotions violates some basic tenets of evolutionary theory: the concept of learned emotions is simply not an Evolutionarily Stable Strategy (ESS). The moment a more effective alternative strategy, such as having innate emotions, is introduced, it will start invading and eventually replacing the unstable strategy of learned emotions, over evolutionary time.

And again, if we want to understand behaviour, we must bring in the evolutionary perspective; the theories that we formulate must make sense when seen through the evolutionary lens.

But in How Emotions Are Made, the adaptive perspective is completely lacking. Nowhere does Barrett discuss which adaptive value emotions might have.

And that is my main concern with that book, and the theory of constructed emotions: it doesn’t make sense from the evolutionary perspective; it doesn’t even discuss adaptation in any way that makes sense.

Indeed, when Barrett mentions Darwin, it’s for two reasons:

- Either she points out that one of the central tenets of the theory of evolution is variability. And that’s true: thanks to mutations, novel genes, novel behaviours and traits are slowly and constantly being introduced into the population.

- She also argues that Darwin’s book the Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals is essentialist (claiming traits having defined properties), stating that “natural selection is completely absent from Darwin’s thinking on emotion”. In this statement, Barrett exposes her own lack of understanding of evolutionary processes. What she fails to mention is that the other central tenet of evolutionary theory is natural selection: that only some of the above-mentioned novel mutations survive over evolutionary time. And that most often, natural selection is not an arbitrary killer, but actually favours adaptiveness: selecting traits and behaviours that increase the likelihood of survival and reproduction of the individuals who carries certain gene variants in comparison with individuals who lack those gene variants. And, as we saw above, any mutations leading to Constructed Emotions wouldn’t stand a chance in the evolutionary race against mutations leading to Innate Emotions.

Because of natural selection, certain gene variants will replace others within a population. Indeed, traits critical for survival get locked into the population; they become evolutionarily stable. Yes, there may still be variation, but that variation is around the new mean, the trait that currently survives the best in the current ecological niche. So, I would argue that Darwin’s book on emotions is not a reflection of essentialism, but rather, adaptionism. A set of emotions evolved because they had tremendous survival value for the individuals who carried those genes – at the expense of those who didn’t. That’s not to say that every single emotion felt by modern humans has tremendous survival value, but the ones put forth by Jaak Panksepp (see below) certainly do.

Also, I believe that the variation that we see in the expression of emotional behaviour in different animals shows that it’s not a case of essentialism, but rather behaviours with similar function adapted to different ecological niches. And naturally, these behaviours will also change through learning, too. Those innate predispositions will be refined through each individual’s unique learning experiences.

Barrett completely misses the significance of the adaptive value of emotions, and indeed, she doesn’t discuss how and when they arose, evolutionarily. Given that she argues that language is a prerequisite for emotions, would it be during the Cognitive Revolution, when the cave paintings started showing up, about 70.000 years ago? Or would it be when the first Homo sapiens appeared, some 200.000 years ago? Or perhaps during the time of Homo erectus, a couple of million years ago? Or how about H habilis?

And how did it all evolve, which came first? The sensation and concurrent action, or the ability to name the sensation? Without both, we wouldn’t have emotions, according to Barrett. I would argue that the sensation/action came first, and the ability to name it came second. Why? Because the action associated with the sensation has clear adaptive advantage, the ability to name it doesn’t to the same degree, if at all.

In “How Emotions Are Made” none of this evolutionary perspective is present. Barrett almost exclusively discusses modern humans, humans for whom emotions serve to consider things like meeting a friend, receiving a gift, hearing favourite music, or arguing with the significant other. She discusses whether stomach butterflies are a sign of infatuation or a viral infection, or that “being angry at the boss” may take the form of silently plotting, yelling or whispering threats.

So, these are Barrett’s examples, from the human experience in the 21st century. And I would argue that these types of examples are completely irrelevant when discussing how emotions evolved. These everyday modern low-stake experiences don’t explain why emotions evolved – in high-stakes situations.

And again, we can’t understand behaviour without the evolutionary perspective, and so in order to understand how emotions came about, we can’t look at the lives and woes of modern humans, but rather we must understand human behaviour from the evolutionary perspective and ask ourselves under which circumstances emotional reactions would be adaptive, that is, save lives.

Humans evolved as hunter-gatherers, and even during most of the 10.000 generations we’ve enjoyed as Homo sapiens, life was incredibly hard: it’s been estimated that half the children born did not survive beyond their tenth birthday, and life expectancy was about 30 years. I propose that under such conditions, we were not “architects of our own experience” as Barrett puts it, but rather seeds to the wind.

We can’t understand how emotions came about by looking at modern humans; I firmly believe that emotions evolved to have some type of function that saved lives in some prehistoric Environment of Evolutionary Adaptedness (EEA), and the crucially important emotions all lead to some type of physical action:

- Running or hiding from predators (FEAR)

- Fighting if caught by a predator (RAGE)

- Caring for offspring (CARE)

- Finding and securing a mate (LUST)

- Vocalizing and actively trying to find companions if suddenly alone (GRIEF)

- Exploring the environment and searching for resources (SEEKING)

- Rambunctiously tumbling about and having fun with others (PLAY)

The actions listed above are just examples from a cluster of potential behaviours that may be displayed for each of these contexts. The seven core emotions listed above (using Jaak Panksepp’s terminology in caps) all make sense from the evolutionary perspective: having these innate responses kick in in response to challenges will help the animal (or human!) survive and reproduce more effectively than an individual who doesn’t show these innate responses, which makes Innate Emotions an Evolutionary Stable Strategy (an ESS) – which, again, the Theory of Constructed Emotions is not.

Emotions serve to launch actions – and these actions are the difference between life or death. This, in my opinion, is how we should attempt to understand and unravel emotions. We won’t understand emotions by talking about how happy we get when we meet Uncle Kevin, or how nostalgic we feel when we remember Grandma’s baking.

Barrett writes: “An instance of emotion, constructed from a prediction, tailors your action to meet a particular goal in a particular situation, using past experience as a guide.”(p 139)

This is the key misunderstanding, in my mind: that sometimes there is no past experience to serve as a guide! That approach will likely get you killed when attacked by a fanged big cat – it’s maladaptive. In contrast, the adaptive response includes some innate predisposition to behave emotionally in a certain manner in a certain context, and then over time, as we learn and acquire experience, we may then tailor our actions to meet that particular goal even more effectively in the future.

Barrett doesn’t discuss Panksepp’s work in any length in her book, other than saying that “some scientists still presume that all vertebrates share preserved, core emotion circuits to justify the claim that animals feel as humans do. One prominent neuroscientist, Jaak Panksepp, routinely invites his audiences to see evidence of such circuits in his photos of growling dogs and hissing cats, and in videos of baby birds “crying for their mothers”. It is doubtful, however, that these proposed emotion circuits exist in any animal brain. You do have survival circuits for behaviors like the famous four Fs (fighting, fleeing, feeding and mating); they’re controlled by body-budgeting regions in your interoceptive network, and they cause bodily changes that you experience as affect, but they are not dedicated to emotion. For emotion, you also need emotion concepts for categorization.”(p 279)

I must confess I am puzzled by these statements. For starters, she dismisses Panksepp without discussing his findings that emotional responses can only be triggered subcortically in specific locations (is she saying he falsified his data, then?). Also, she acknowledges the four F – types of behaviours but claims that they’re associated with “affect” but not “emotion” without any further explanation – which in a way suggests that this whole discussion is about semantics rather than whether or not specific behavioural systems evolved to resolve different types of critical situations.

Indeed, Panksepp distinguishes three levels of emotional processing, primary level processing (the 7 Core emotions listed above and originating subcortically), secondary level processing (learning, expanding to other regions in the brain) and tertiary level processing (thoughts about emotions; involving the cortex). It would seem that Barrett only considers the tertiary level “emotions”, calling the rest “affect”..?

So, how we define “emotion” matters. In my understanding, evolution granted us some core affective reactions that have survival value and that can’t rely on words to be effective, since they are shared by all mammals. These primary level affective reactions must therefore occur without words, and perhaps then also without concepts. I choose to call these primary level affective reactions emotions, Barrett does not.

And you may think of emotions as subjective experiences, feelings. Sensations in the body and mind. The elation of joy, the pain of loss, the terror of fear. In our day-to-day modern lives, that’s often how they make themselves known, through subjective sensations.

That’s how we primarily experience them, so that’s what catches our attention. But that doesn’t explain why they evolved.

Emotions didn’t evolve so that we could just feel them.

They evolved to spur us into life-saving action. Emotion is “energy in motion” and the word is derived from a Latin verb meaning “to move.” Emotions came about as innate responses to challenges. Which is why I believe that those four Fs that Barrett dismisses as a result of affect would also be involved in emotion.

Thus follows that we should be able to find out how these Core Emotions, crucial for survival, are processed in the brain. Since they must be innate, we expect there to be different areas of the brain dedicated to dealing with these crucial challenges. We expect a blueprint that can spring into action without any prior learning – we expect Core Emotions to involve specific brain regions.

We don’t expect every single emotion that’s known to mankind to involve specific brain regions, but specifically those with tremendous survival value.

I can think of seven, identified by Jaak Panksepp and colleagues: CARE, GRIEF, PLAY, LUST, SEEKING, FEAR, and RAGE: the Core Emotions.

And again, Panksepp identified these 7 Core Emotions by sending small electrical currents through subcortical brain regions of multiple species of animals including humans, and noting that they all responded with similar reactions indicating similar emotional responses, each originating in a distinct area in the brain. His human subjects would show specific emotional facial expressions and report corresponding emotional reactions when each specific area of the brain was stimulated.

Note that what he found typically involved emotions being triggered in the different subcortical areas, and then rapidly spreading throughout other areas in the brain. This is in contrast to the so-called “classical” view that Barrett purports in her book: as far as I understand she suggests that the “classical” view would view emotions as localized only to specific areas in the brain rather than spreading from specific areas.

Note also that Panksepp could only trigger emotional reactions in the subcortical areas, the most ancient parts of the brain whose structures are roughly similar in all mammals and birds. He couldn’t trigger emotional reactions by stimulating the cortex.

Panksepp also found that several of the core emotions are active when animals are young, and diminish as they grow older: when higher brain functions take over, and become more dependent on learned behavioural strategies.

In the book The Constructed Theory of Emotions, Lisa Feldman Barrett completely ignores Panksepp’s and his coworkers’ 30+ years of data. She does not refute it or point out if and why it’s erroneous – she simply ignores it.

Rather, she says that there’s no evidence that specific emotions are processed in specific regions of the brain, and she bases most of that assertion on a big meta-analysis.

Meta-Schmeta.

Fair warning, I’m leaving safe ground now. I’m an ethologist, not a statistician, and even though I did study statistics as part of my phD, it was never my strong suit. So what follows could be wrong in several ways, and I’m counting on you, my statistics-minded reader, to set me straight.

A meta-analysis is a way to combine and analyze data from multiple studies. In this way, effect estimates are obtained with greater precision due to the increase of the sample size, and it’s considered the pinnacle of scientific evidence, the type of study that can decide a controversial issue once and for all. Meta-analyses carry tremendous weight and are the highest level of evidence, because they consider all the available data and pool results to summarize a whole body of research.

And that’s what Barrett and coworkers did:

“So, my lab set out to settle the question of whether brain blobs are really emotion fingerprints once and for all. We examined every published neuroimaging study on anger, disgust, happiness, fear and sadness, and combined those that were usable statistically in a meta-analysis. […] Overall, we found that no brain region contained the fingerprint for any single emotion. […] For me, these findings have been the final, definitive nail in the coffin for localizing emotions to individual parts of the brain.”(p 21-22).

So, if a meta-analysis pooling “every study” together draws the conclusion that there are no specific brain regions involved in any specific emotions, that must be true, right?

Nail in the coffin, right?

Well…

I’m having huge doubts, for a couple of reasons.

One of the limitations of a meta-analysis is that in order to be able to include data into the analysis, the data need to be similar, and measure the same thing in the same way.

The data must not be heterogeneous, as it were.

If it’s heterogeneous, the variability in the data will obscure any true findings, and we risk a false negative outcome.

Apparently it’s one of the more common mistakes people make when conducting a meta-analysis: combining heterogeneous data. One study suggested that about 3,75% of currently published meta-analyses are decent and clinically useful, the other 96,25% being flawed beyond repair, misleading, decent but useless or redundant.

Chew on that for a bit.

96% of meta analyses lacking in some way. So we should always be critical thinkers when faced with them, even in peer-reviewed published papers in prestigious journals.

So, rather than taking Barrett’s meta-analysis at face value, I questioned it. After all, it only had 3,75% chance of being decent and clinically useful.

And after reading through the abstracts of the 60 first references of the studies included in the meta-analysis, I quickly discovered that the data included were not measuring the same thing, and they were also not collected in the same way; rather it was extremely heterogeneous.

Here’s how emotional reactions were triggered in some of the studies in the meta-analysis, using either fMRI or PET (measuring blood flow versus blood oxygenation):

- Film-induced sadness/amusement

- Looking at neutral and negative scenes

- Looking at angry and fearful faces / sadness

- Looking at happy/fearful faces and hearing happy/fearful voices (or mix)

- Passively viewing emotion words

- Matching emotional face with words

- Viewing photo of beloved while being in love

- Watching a filmed bank robbery in which they had been the victim.

- Recalling emotional situations that they have lived through: (sadness, happiness, anger, fear, disgust)

- Listening to an autobiographic narrative meant to cause anger

- Listening to angry prosody in meaningless speech

- Olfaction / tastes and core affect space

- Pairing faces to neutral, pleasant and unpleasant odors

- Listening to music that produces the chills

- Mentally preparing a speech to be presented to a panel of professors and experts

- Comparing depressed / healthy people viewing sad film

- Comparing panic disorders/ controls viewing anxiety-inducing images

- Comparing borderline / controls viewing aversive and neutral images

In other words, the data was all over the place, both with regards to measuring technique (fMRI versus PET), which purported emotion they were measuring, how that emotional reaction was triggered, which sensory system was involved in processing the trigger, whether the study involved primary, secondary or tertiary level emotional processing, whether the studies looked at emotion experience, perception, memory or categorization, as well as the emotional baseline state of the person when the experiment started.

Not to mention that all of these were carried out on humans who were aware of being part of an experiment, so one might question perhaps how authentic the purported emotional reaction would be to, for instance, listening to an autobiographic narrative meant to cause anger in such a highly contrived scenario. Might we expect “real” anger to be triggered and processed differently in the brain? And is a social evaluative threat, fear of giving a speech in front of an audience, really fear – or some other emotion, such as embarrassment?

In other words: garbage in – garbage out.

Meta – Schmeta.

Another problem I have is that the findings of a particular meta-analysis may be valid only for a population with the same characteristics as those investigated in the study. In other words, the results of Barrett’s meta-analysis would be valid for people undergoing this type of contrived experiment, where “emotions” (if that is indeed what they are) are triggered by images, video, odors or sounds while strapped into a laboratory apparatus. We can’t extrapolate to real-life situations, because that’s not what they studied – and we don’t know how well biologically meaningful situations correlate with these artificial experimental set-ups.

Also, due to ethical reasons, truly distressing emotions are never evoked in these types of experimental studies included in the meta-analysis – so we simply don’t know what goes on in human brains experiencing intense negative emotions.

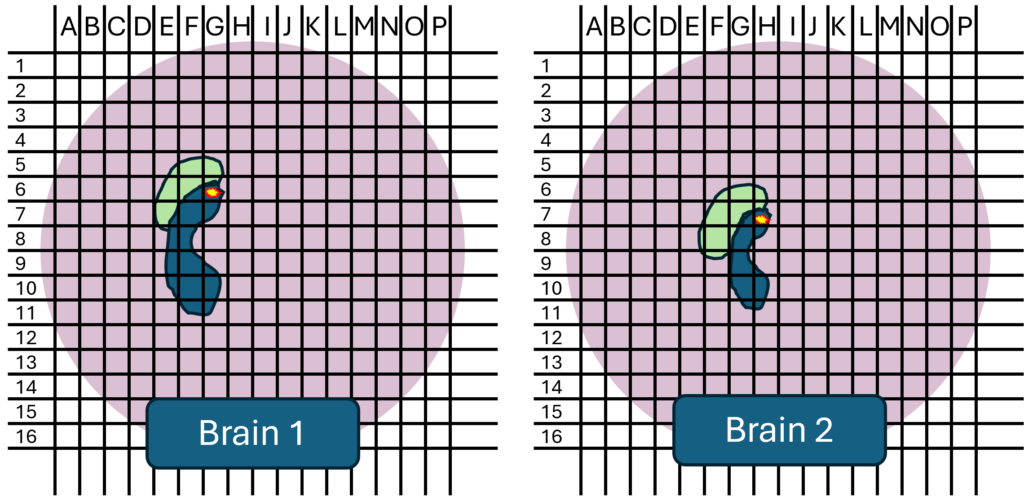

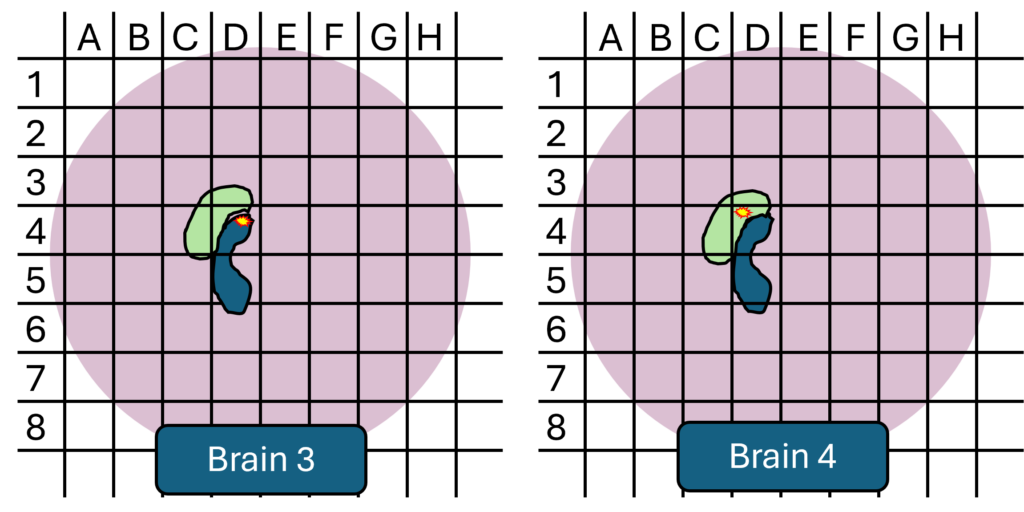

Another issue with Barrett’s nail-in-the-coffin meta-analysis that makes no sense to me whatsoever is that Barrett and coworkers chose to virtually divide the brain into tiny 3D-cubes (voxels) to analyze the data:

“For every voxel in the brain during every emotion studied in every experiment, we recorded whether or not an increase in activation was reported.”(p 21)

And here’s my problem: when looking for brain blobs (or localized networks dedicated to processing different emotional states), the voxeling approach can lead to either false negatives or false positives depending on the chosen voxel size.

Let’s look at two hypothetical scenarios to illustrate my objection.

First, since no two human brains are exactly similar in structure, a specific voxel, if small enough, may be located in different structural regions in two brains. So, even though the same brain region were activated in both brains, different voxels would be activated – a false negative.

The risk of a false negative is increased with reduced voxel size.

Indeed, in chapter 11 Barrett writes: “No two brains are exactly alike. They generally have the same parts, roughly in the same place, connected together in pretty much the same way, but at a fine-grained level, in their microcircuitry, they have vast differences” (p 230). This statement, to me, completely invalidates the voxeling approach.

But we’re not done yet – there’s also hypothetical scenario two – when voxel sizes are too large.

The risk of a false positive is increased with increased voxel size.

I would argue that the choice of voxel size for this study is thus most likely biased: if one wishes to prove that brain blobs don’t exist, one is more likely to choose small voxels and obtain a negative result that proves one’s thesis – so that one can triumphantly proclaim that one has successfully hammered the final “nail in the coffin”.

Even if we assume that we could find a balanced voxel size that would yield neither false negatives nor false positives, that would probably only be true for some emotions and some brain blobs in some brains. Other emotions might involve other brain blobs, requiring a re-calibration of voxel size – and we would have no way of knowing if we had found that balance unless perhaps we also look at whether our voxels align with defined neurological structures that might house such brain blobs, such as amygdalas, hippocampuses (or is it –campi?) and whatnot. However, I doubt that those balanced voxel sizes even exist since no two brains are structurally identical – we will either fall into the false negative or the false positive error, and our biases will predispose us to choosing one or the other.

Meta-analyses are a controversial tool, because even small violations of certain rules can lead to misleading conclusions. Since multiple decisions when designing and performing a meta-analysis require personal judgment and expertise, there is a substantial risk of personal biases or expectations influencing the result.

Indeed, in his scathing critique of the current Meta-analysis fad, John Ioannides writes: “Ideally, people who have no stake in the results should perform systematic reviews and meta-analyses, excluding not only those with financial conflicts of interest but even those who are content experts in the field.”

In this case, omitting Panksepp’s data altogether (they were indeed missing despite the claim to include every published neuroimaging study) while throwing in a heterogeneous bag of other studies is a way of cherry picking data that concerns me, and I think that the findings reflect the biased selection of data, the heterogeneity, and the overwhelming risk of a false negative result obtained through voxeling.

Also, in the meta-analysis they tested the assumption that each emotion is processed only in one specific brain area, calling this the classical, locationist perspective, and they took any failure to find such associations to mean that emotions would be constructed, rather than innate. An alternative explanation may be rather that emotion processing is not limited to a single location but rather part of specific networks connecting several regions, extending throughout the brain – which in fact is what Panksepp has suggested all along. Brain regions do not function in isolation, but rather in the context of the networks to which they belong.

Others have criticized Barrett’s and coworker’s meta-analysis, and one of the most convincing arguments that I found was put forth by professor Andrea Scarantino:

The authors “…are open to the possibility that there may be “widely distributed” networks for discrete emotions, but argue that their existence “would be consistent with a psychological constructionist … view” (sect. 6.1, para. 4). I strongly disagree. Constructivism posits that discrete emotions are not causal entities in their own right, but rather, effects of more basic psychological processes. The existence of networks for discrete emotions would strike at the heart of this idea, vindicating instead the natural kind proposal that discrete emotions have ontological status as causal entities and are driven by distinctive, though distributed, neural mechanisms. [The authors have] built their argument such that if criteria for the locationist argument are not met, it is assumed to be support for the psychological constructionist perspective. This is misleading, and fails to recognize other possible explanations.”

Another shortcoming of the study was that fMRIs typically only capture the initial response to an emotional stimulus, and we know nothing of what happens over time; this type of measuring technique doesn’t capture the development of the emotional experience beyond the first second or so. Panksepp typically used PET studies rather than fMRIs, much for this reason if I’m not mistaken.

To summarize, it’s not surprising that the meta-analysis found nothing, or rather, it found a huge variability in how emotions are processed in the brain, given that the included data was too heterogeneous; despite the heterogeneity there was still cherry picking with critical studies omitted; the use of voxels rather than comparative anatomy may obscure any real findings and further increase the chance of false negatives, and we don’t know how well the contrived experimental set-up translates to real-life emotional reactions.

So, there’s no way of distinguishing whether those results were a false negative or a true negative result.

For me, Barrett’s meta-analysis was by no means any nail in the coffin with regards to how emotions are processed in the brain.

Indeed, using Ioannides’ classifications of published meta-analyses, Barrett’s nail-in-the-coffin one would classify both as flawed beyond repair (see the Catch 22-reasoning below) as well as misleading. Yes, that’s a harsh judgment coming from someone who doesn’t know much about statistics. I’ll grudgingly change my mind if you prove me wrong, though!

And even if I didn’t have these glaring objections to Barrett’s meta-analysis, I would still be concerned.

Why?

Because I would expect the brain to be involved, in some way. Since in the previous section we discussed the need to run from big fanged cats, that needs to be choreographed by the brain, without prior learning, somehow.

Yes, I would expect learning to occur, naturally, but I’d also expect innate emotional reactions orchestrated by different sections in the brain.

In other words, I’d expect to see what Panksepp actually did find.

Barrett writes: “I sometimes hear comments from emotion researchers who subscribe to the classic view: “what about these other 50 studies with these thousands of subjects, that show incontrovertible evidence for emotion fingerprints?” Yes, there are many such confirmatory studies, but a theory of emotion must explain all the evidence, not just the portion that supports the theory”. (p 22)

She makes a valid point that all evidence must be explained by a theory of emotion. But the studies of emotions in the brain carried out to date simply don’t lend themselves to a relevant meta-analysis, since they’re too heterogeneous, and any selection of studies to include into a homogeneous meta-analysis would be biased one way or another and contain only a fraction of the studies carried out.

Meta-analyses for emotion studies are a catch 22, as it were:

- If we try to do a rigorous meta-analysis and only choose a homogeneous sample of studies measuring the same thing in the same way, the selection would have to be only a fraction of all emotion studies – with a huge risk of selection bias: choosing studies that prove one’s point.

- If we try to include all studies (as Barrett and co-workers did), the selection will be heterogeneous – and there’s a huge risk of false negatives due to the noise in the data.

Damned if we do, damned if we don’t. There’s simply no way to thread that meta-analysis needle, as far as I can tell.

Not sure why we would need one, though? Rather than insist that all emotion studies should obediently line up in a huge meta-analysis, couldn’t we flip the burden of proof and say: if emotions were truly constructed, how come those 50 studies showed evidence of emotions being processed in the same parts in those thousands of brains? Wouldn’t we expect complete variability within each of these studies if emotions were indeed constructed?

Also, one disturbing omission in the book is a discussion on neurotransmitters. Barrett searches for, and dismisses, “fingerprints” on emotions related to facial expressions, and brain areas involved in emotions. But she doesn’t address what we know about neurotransmitters associated with emotions (oxytocin, dopamine, endorphins, and endogenous cannabinoids to mention a few), how they are involved in emotional reactions or how the synapses where they take action are distributed throughout the brain. How well do these findings reconcile with a Constructed Theory of Emotion? I suspect not well at all, but I could be wrong.

Let’s leave the brain behind and move on to another topic: whether facial expressions are innate or rather learned, as suggested by Lisa Feldman Barrett and the Theory of Constructed Emotions.

Facial expressions

In the book, Barrett shows snapshot images of partial facial expressions, making the relevant observation that we can’t reliably decode an emotion from seeing an image of a part of a facial expression.

Barrett then goes on to make the case that we can’t tell emotions from facial expressions because they’re too variable, and it’s only in context that we understand what the person might be experiencing, and on top of that it’s only if we share similar learned expectations about what facial expressions should mean (smiling means happy, frowning means angry, etc) that we can interpret them.

I disagree.

Rather, I would say that we didn’t evolve to decipher emotions from snapshots of partial facial expressions, so we shouldn’t expect to be able to do that. We evolved to understand a subset of facial expressions unfolding in real life and over time in relevant contexts.

Again, everything in biology must be understood from the evolutionary perspective.

So, the crucial question is: when would innate facial expressions be adaptive? If we look at what type of situations that we would expect to result in adaptive stereotypical facial expressions or body language signals, it would be in some social contexts, such as to signal intent (benign or malign), as well as to realign the face or body to better deal with environmental challenges (the scrunchy nose face that’s often associated with disgust for instance, may serve to close the nasal passage protecting it from dangerous fumes, and squinting our eyes shields them from damage).

And in my understanding, the human smile doesn’t necessarily mean “happy”, but rather it’s a social signal of benign intent. From the evolutionary perspective, it’s highly adaptive to be able to recognize if a person has benign or malign intent even from a distance, and so we would expect that there would be a selection pressure favouring that type of signaling.

But again, the adaptive perspective is completely lacking in Barrett’s book. She simply concludes that decades of studies of facial expression are faulty, that we learned to smile by watching TV, and so she rejects the notion of innate facial expressions altogether.

In Barrett’s words, according to the classical view, “emotions are supposed to have universal fingerprints that everyone around the world can recognize from birth”. (p 43)

I’m not sure who claims this – who makes that argument? Over and over while reading the book, I get the feeling that much like Don Quijote, she’s tilting at windmills. She’s attacking a straw man, one that doesn’t exist. The simplistic “classical view of emotions” that she attacks isn’t actually argued by anyone, as far as I’m aware. There are more than 92 definitions of “emotion” in the scientific literature – which is the “classic” one?

As to her quote above, from the evolutionary perspective, I would neither suppose that every single emotion is matched by a specific facial expression, nor that we could necessarily be able to recognize those expressions from birth. There’s no adaptive reasoning that would suggest that any of those two statements would be true.

I won’t go into much detail of Barrett’s arguments here, but Paul Ekman defends his research on facial expressions here, and a Nature paper summarizes much of the controversy here.

Here’s a passage that I had to read several times, though, feeling my jaw drop.

“The historical record implies that ancient Romans did not smile spontaneously when they were happy. The word “smile” doesn’t even exist in Latin. Smiling was invented in the Middle Ages and broad toothy-mouthed smiles […] became popular only in the eighteenth century as dentistry became more accessible and affordable. The classics scholar Mary Beard summarizes the nuances of the point: “This is not to say that Romans never curled up the edges of their mouths in a formation that would look to us much like a smile; of course they did. But such curling did not mean very much in the range of significant social and cultural gestures in Rome.” “ (p 51)

I’m not sure on which data this classic scholar rests the conviction that Romans didn’t smile, and although I’m fascinated by the idea of time travel, in my mind the only two relevant sources might be literature, or art.

I would not take the lack of discussions of social smiling in the Roman literature to necessarily mean that people didn’t smile: the absence of evidence is by no means evidence of absence.

But even more importantly, I can think of one huge reason why smiling would be expected to be absent from Roman art: because smiling would indicate benign intent. And when you’re getting your formal portrait made, whether you want to come off as powerful or friendly will surely differ depending on the cultural climate. And I can think of no epoch when the projection of power were more important than during the Roman era.

We always need to think about alternative explanations to our observations, and the lack of smiling portraits or sculptures from the Roman era might either mean that people didn’t smile at all, as Barrett assumes, or that smiling wasn’t something that was captured in art during that particular era – which in my mind is a vastly more plausible explanation.

As to the statement that “the word “smile” doesn’t even exist in Latin”, what about subridere? Does it not mean “smile”, or is it not Latin?

Silent bared-teeth displays, signaling benign intent, is shown in gorillas, chimpanzees, orangutans and macaques – our closest relatives. To suggest that smiling in humans came about in the Middle Ages doesn’t align well with these comparative findings. Frankly, it’s preposterous.

In my opinion, Barrett throws the baby out with the bathwater by suggesting that all facial expressions are learned, rather than some being innate. Looking at someone’s face and understanding their emotional state and intention – without prior learning – has tremendous adaptive value. We’re often more honest in our facial expressions than what we communicate verbally. What we say about our emotions is often incomplete, faulty and adapted for the public – censured.

Besides, if emotional facial expressions were truly learned, surely there’d be more variability? Would smiling-when-greeting-a-friend or frowning-when-annoyed be that ubiquitous, seen in all cultures around the globe? If they were truly culturally transmitted, wouldn’t we expect as much variability in facial expressions as in, say, language?

The importance of the discussion climate

So why did it take me 3 years to read How Emotions Are Made? Well, to me personally it was an extremely aversive read, and after the first chapter I put it aside and kept stewing over it for a very long time before I picked it up again, months later. Here are the main reasons why it was so difficult:

- Barrett challenged my core beliefs: I’m a firm believer in emotions being innate, and she kept telling me I was wrong.

- Her tone of voice while telling me I was wrong was extremely condescending, and I’m a sensitive person prone to indignation and affront when patronized. My adrenaline kept spiking, so I kept putting the book down.

- I felt myself disagreeing with many of the scientific studies reported in the book (I’ve only mentioned a few of those disagreements in this blog post, but there’s more!), which made reading on very difficult because I got so biased to thinking that I would continue to disagree. I actually found that I was mostly in agreement about chapter 9, though!

So, rather than convert me, the book did the opposite: I finally plowed through it on sheer willpower (lots of chocolate as reinforcement after each chapter), and put it down being even more convinced that I was right. I realize this might sound like quite the absurd reaction, and part of it has to do with the Semmelweiss effect and the backfire effect, two cognitive biases that both kicked in.

But also, I truly believe that the Constructed Theory of Emotions is flawed. Those cognitive biases merely exaggerated my reaction to the book.

Lisa Feldman Barrett concludes in her book that “based on overwhelming evidence, the classical view has lost”. (p 152)

I’m actually underwhelmed, and remained unconvinced by most of the evidence she puts forth; my paradigm hasn’t shifted. But she doesn’t invite discussion, but rather accuses people subscribing to the “classical view” of the mental inference fallacy, and of being unscientific:

“When mountains of contrary data don’t force people to give up their ideas, then they are no longer following the scientific method”.(p 173)

I find that statement extremely triggering. I am following the scientific method to the best of my ability, and I’m also questioning her theory.

But although I’m guilty as charged, I’m most certainly biased by the mental inference fallacy, that’s not the reason I’m disputing her claims. I dispute them because I don’t think that the Constructed Theory of Emotion is based on any solid science, and that what is needed here is discussion, not polarization and condescension of the opposing viewpoints. Any Theory on Emotions should incorporate all the main findings and still make sense from the evolutionary perspective – without ignoring Panksepp’s and others’ large body of work. I just don’t think that meta-analyses are useful for this discussion since we risk either false negatives, or biased selection of data.

To me, the Constructed Theory of Emotions is about how we think about our emotions, and how we classify them. Not what triggers them, and how we respond to them – which behaviours we show, or what the outcome of those behaviours are; how they were once (and perhaps still?) adaptive. Indeed, Frans de Waal suggested in Mama’s Last Hug that we make the distinction between emotions (objective, measurable, physical, affective reactions resulting in observable behaviour) and feelings (subjective, conscious experiences of those emotions).

Using that terminology, Barrett’s theory might perhaps better be named the Constructed Theory of Feelings.

Why it matters

So, why did I get so tremendously triggered by this book, and by the fact that large portions of the animal training community thinks the Constructed Theory of Emotions is the best thing since sliced bread?

Because it puts humans on a pedestal, and demotes animals to… something else entirely.

I’m no longer in academia, nowadays I spend my time helping pet parents and animal professionals get happy animals that are reasonably well behaved, through online courses, seminars and blog posts. And hands down, I’ve found that the best way to obtain a harmonious relationship with the animals in our care is by acknowledging that they have emotions.

The horse that refuses to load into the trailer is probably anxious.

The dog that shreds the furniture when left alone is likely panicking.

The cat that lashes out at the veterinarian’s table might be terrified.

We can help them by changing their moods and emotions: very often the behavioural manifestations of their emotional turmoil will disappear if we manage to help them regulate their emotions. But if we don’t even acknowledge that they have emotions, we’re left with a much smaller toolbox to help them change those unwanted behaviours.

There’s a more sinister side to it, also.

By putting ourselves on a pedestal and demoting animals to the other, we create a rift between “us” and “them“.

Just take a look around the world to see how we humans treat people that we categorize as “them“, that are not part of our own tribe. We might at best ignore them, and we do unspeakable things to our enemies.

In other words, widening this rift between humans and animals opens the door to sanctioned cruelty.

To quote the philosopher Jeremy Bentham from 1789 on whether it’s morally acceptable to inflict pain on animals: “The question is not, can they reason? Nor, can they talk? But, can they suffer?”

Yes they can. In the last few decades, we have learned that many animals have consciousness and Theory of Mind, they can plan ahead and show cultural learning, and although we can only guess what they’re feeling, we can’t assume that they don’t feel. And yes, they certainly have emotions.

By acknowledging not only their emotions but also their feelings, we can reduce their suffering.

***

I write the occasional blog post, run silly experiments, and give free Masterclasses as well as extensive online courses, all on the topic of animal behaviour, learning and wellbeing. If you’re interested in being notified about when any of these things happen, just sign up below, and I’ll keep you posted!

240 replies on “My problems with the Constructed Theory of Emotions”

Thanks for this. I am in the middle of listening to this book now. I am not a scientist, just a curious person. The Book sounded interesting. Sure, I would love to know how emotions emerge. I had no idea it would be a controversial new theory.

But as I was listening, I was thinking, “Am I misunderstanding her? Because the way I hear this, this can’t possibly be true. That we don’t have emotions unless we have a label for that emotion? What about animals? What about a hypothetical person living in isolation? This doesn’t make any sense. Even if there were no literal “fingerprints”, that just suggests that there is a certain amount of plasticity in the brain.

This also seems like a version of the blank slate, which we know is not the case.

It is nice to see that, at least I am not missing her point.

No, I don’t think you’re missing her point… 😉

A brief follow-up. As you say:

“And that’s why I first stopped reading the book How Emotions Are Made after the first chapter, because the theory of constructed emotions violates some basic tenets of evolutionary theory: the concept of learned emotions is simply not an Evolutionarily Stable Strategy (ESS). The moment a more effective alternative strategy, such as having innate emotions, is introduced, it will start invading and eventually replacing the unstable strategy of learned emotions, over evolutionary time.”

I intuitively had the same reaction; but unlike you I did not conclude that she was mistaken; I concluded that I simply didnt understand what she was saying, because clearly she couldn’t mean that.

This is interesting to me because of the way it illuminates how we create meaning. My strategy for reading is to always assume that the author is in some sense correct, or is at least saying something meaningful; I just need to try to see it from their point of view to understand what they are saying. A strategy founded in empathy you might say (which I would imagine appealing to an ethologist). I could logically justify this strategy, I think, by reasoning that it is really quite difficult to put jibberish into good grammatical form.

Lisa Feldman Barret seems to have somehow managed to write a book not so much on a coherent theory of emotion, but on how to apply (or not to apply) the scientific method; and to have created an environment in which to explore how emotion shapes meaning making strategies.

I understand that your primary interest is in something like creating a better world for our animal relatives, but do you think that if humans learned to incorporate their ability to sort out their emotional responses into their ability to reason “scientifically”, that might prove helpful?

At any rate, your blog post convinces me that you could have some really valuable things to say about it – an entire book devoted not just to scientific method in the abstract, but to what it means to us “subjectively” – why we give a damn.

Hi Mark, and thanks for sharing your thoughts! For me, the ability to question authority is actually a learned skill. I didn’t use to do it, but I remember vividly how, as I was starting my thesis, I had a follow-up meeting with two senior researchers. I explained how I had been told by an authority to proceed in a certain way, but that I didn’t quite feel comfortable doing it, but since they suggested it, it must be right. The two researchers both leaned forward, at the same time, and interrupted me. “you must absolutely question them!!” “don’t assume that they know what they’re talking about!” they almost yelled at me. It was a defining moment… and since then I find it much easier to question even seemingly well-founded ideas. 😉

Quote: In this particular case the question would be: “would someone who constructed emotions do better, or worse, than someone who didn’t construct emotions?”, or perhaps rather “would someone who constructed emotions do better, or worse, than someone who had innate emotions?”

From an evolutionary point of view only the first question is correct. It is the question, why constructed emotions might have evolved. The second question is comparative and suggests construction as evolvement principle – nature simply uses the better model – but that’s not how evolution works.

And: why did Feldman Barrett develop the theory of constructed emotions? Because she could not find any evidence of innate emotions, quite in contrast, she, her team and many other researchers found evidence, that there are no innate emotions – even so this is in total contrast to all previous theories and yes, very counter intuitive.

I’d say that both questions work: if both strategies were evolutionarily stable (both ESS’s) we might expect that they might find a balance and co-occur – but out of the two, only the strategy of innate emotions is an ESS.

The term ESS itself is very misleading, evolution has no strategy.

And yes: for creating innate emotions, you would need a strategy and a long term plan to make it happen – so devenitely not evolution’s cup of tea.

The term ESS is used by evolutionary biologists to describe how come some mutations survive over evolutionary time at the expense of others. The term strategy doesn’t imply intent here – it’s simply a way to name this well-documented phenomenon.

Exactly 🙂 … and see what happens …

Or can you describe any evolutionary line, along which innate emotions could have developed?

And see, all the evidence for constructed emotions, and no evidence, but just claims for innate emotions.

I am always amused when people say “I see your evidence, but I do not believe it” – and they themselves claim something without any evidence. But for scientists this must be very tiering and anoying, so I really understand Lisa Feldmann-Barrett in her attitude.

Hi there, great blog post, I agree. I would however be careful with the voxel argument. I myself am an ethologist by training, but for my PhD also have done work in neuroimaging, especially with voxel-based analyses. There is a standard size for voxels that is often used, and brains are normalized to a standard brain, so the variability among scans is often not really a consideration, especially with voxels. I hear your argument about false negatives, this is a limitation of the field, but it’s not as crude as you make it out to be. Regardless, I agree that the CToE is largely flawed; I would just be careful with your voxel-based arguments. Also, there are many techniques used in meta-analyses to standardize them as best possible; there is less heterogeneity than you would expect, as scanners, sites, and types of scans are often controlled for (along with many other co-variates). Great article though, thank you!!

Thanks for your input, Alex! A question then, if I may – perhaps you know the answer? is the voxeling (which I suppose is simply some sort of coordinate that’s been calculated and standardized based on head size) also aligned to some type of imaging showing different brain regions? (allowing for recalibration based on whether the actual physical structures deviate from the norm?)

Yes, that is exactly it. You can calibrate it to what a normalized structure would be. It really depends on your analysis and what regions you’re targeting, but if this is important, it is something you can do. It’s not perfect, but there are algorithms to normalize to structure, not just whole brain indeed.

Would you have a guess at the extent to which this is done..? Do most studies calibrate like this – and if so, could it be that there’s a difference between older versus newer studies on that point..? 🙂

Nuance – spatial normalization of different brains to a common template doesn’t work perfectly, and different people may have different functional anatomies. So an additional step of smoothing, or averaging neighboring voxels together, is also usually performed to mitigate the differences in anatomy that persist after normalization. This can have some unintended consequences though, like blurring out small focal points of high activity for example. I’ve also seen it said a lot that subcortical structures are much harder to record from with fMRI (they have a low signal-to-noise ratio), and in this case newer machines (7T scanners) are more helpful.

But, even before that is an issue, I agree with the author that construct validity is more of a problem. Likely, a lot of these studies don’t activate “true” emotional responses since that’s difficult to do in an artificial environment, inside a scanner etc. In my lab we use animal videos and people with subclinical phobias, which seems to do the trick.

Thank you for your post, it was insightful to read that critique of the theory of constructed emotions. For context, I have a background in cognitive neuroscience, and beginning to dip my toes more specifically in the domain of affective neuroscience. It was refreshing to read your post as I think it lays your ideas in a really digestible way (something that is sometime missing in theoritical scientific article).

I still need more reading to properly form my reflexion, but I mainly wanted to add some precision regarding the neuroimaging information you provide in your blog. Maybe others have pointed that out, but I must admit I haven’t read all the comments (amazing the level of engagement that post got!), so please feel free to ignore:

– The “voxeling” approach is unfortunately something that we can’t really work around when we are doing neuroimaging, it’s just the way we acquire the signals. We need to consider a trade-off between spatial resolution and temporal resolution. Usually, the smaller the voxel (better spatial resolution), the worst the temporal resolution (less timepoints acquired for a given time). fMRI studies will often use a spatial resolution of 2mm x 2mm x 2mm to 3mm x 3mm x 3mm, which is quite big if we think about it, and your points are valid. We are getting better at it (technological advances: stronger magnets for MRI apparatus, different acquisition sequences, etc.), but it is a downside of doing neuroimaging on humans in a non-invasive way.

– Also regarding the point illustrated in one of your figure, one of the steps in fMRI preprocessing is taking the brain of all your participants and putting them in a reference space to make sure that we compared the same anatomical regions across all our sample (a step called registration in a reference space). More recent, and exciting, work is not only looking at the anatomical level, but also at the functionnal registration (see hyperalignment techniques) to provide a more robust way to study brain activations across participants !

– The temporal resolution of PET is actually not better than fMRI. Doing PET using oxygen-15 to measure indirectly the cerebral activity is relying of the same physiological principles as fMRI (i.e., the neurovascular coupling). Also PET imaging does not provide a better spatial resolution than fMRI.

So there are some limitations in studying the brain using fMRI (just like any other technique), but it will be interesting to see how the field of affective science evolves, and if advances in imaging and computational techniques improve our understanding of emotion processes in the brain !

Best !

Hi Marie, and thanks for adding your thoughts on this topic! Sounds like the use of a “reference space” would be the way to reduce those two problems with the voxeling approach..?!

As to Panksepp’s preference for PET over fMRI, I don’t quite recall his argument so I might have misrepresented his stance on this (or techniques might have changed/improved since he did his research)…

Hi Karolina,

I’ve got some thoughts I’d like your opinion on. I think Barrett’s explanations might be wrong, but her observations may not be.

Hi Ameet, which observations are you referring to? 🙂

Hi Karolina, my apologies, but I don’t remember what I was thinking when I said that now. It doesn’t matter. What I wanted your opinion on, was a Belief Formation Model (BFM) I’m working on, which I believe might satisfy both sides of this debate. Or at least, provide a bridge that can be built upon by others.

I think emotions are predictive signals, indicating that a belief is being tested. If the belief (the actual prediction) can be changed, the emotion no longer triggers. This is based on my own inside-out thinking (long story) and I’ve started accumulating empirical evidence, starting with myself but that has now spread to others in my early testing and fine-tuning.

I come from a longtime CS background, a more-than-passing interest in psychology (due to an interest in AI and my own cognitive challenges), and my independent research into AI. I’ve concluded, that the training of LLM Artificial Neural Networks is analogous to our own emotional training during childhood. Just like with LLMs, if we don’t update our models when we enter adulthood (inference for LLMs), we run into problems surviving and thriving.

I’m staunchly in the Nature-first camp. I believe that everything a living creature does, revolves around its interpretation of what will keep it safe. Obviously that includes us humans, but in fact, I think Nature is the real one playing this game-of-life, not us. We’re just another dice-roll. If we fail, whatever intelligent life that follows us in 500M years will at least have our cautionary tale in their existential tool-belt.

I’ve developed my model further since I made that first post. I posited that it should be possible to deliberately induce cognitive dissonance events, for which Nature has already provided the resolution tools for in order to reduce the negative effects that result from carrying distorted beliefs; beliefs which were once helpful for our personal survival, but no longer.

In my personal life, I have “graduated therapy” in that I’ve formally ceased my fortnightly sessions with a clinical psychologist, as I can now rapidly process unresolved trauma in a way I don’t think anyone has been able to before (at least, not in a way that I’ve been made aware of). I’ve run them on myself, noticing profound and lasting changes, and I’m currently building a system to make them less manual, so that wider testing can begin. This process is called Engineered Cognitive Dissonance Events (ECDEs), and is based on the BFM I mentioned. It’s important to note that this BFM is just my mental model of how my own brain works. The explanation doesn’t matter anywhere near as much as the ECDEs do, because those now appear to work for more than just myself, and are profoundly more useful, but it would be good to see how it sits for others.

I assume you can see my website or email address. Please get in touch, it’s going to be hard to continue a conversation here! My website has some brief draft papers that explain things a bit more if you’d like to review them before reaching out. I look forward to hearing from you.

Hi Ameet, I’m sorry but at present I don’t think I have the bandwidth or time to delve into another emotion theory, no matter how interesting – unless it would be relevant for my work helping animals..? But if your technique is that promising, hopefully you should be able to get it picked up by someone working with humans. Best of luck! 🙂

Interesting, well my work applies to AI as well as humans…so I’d expect it to apply to animals as well. Anything with a Neural Network brain.

I’ve successfully used a form of ECDEs on my pet cat, who was a shelter cat. Her anxiety has been 95% healed. That was part of how I built the theory, but anyway, no worries.

I see! Can you give the short version of how you helped your cat? 🙂

None of your are studying Humans in a free state. We operate on the basis of memory, cellular memory even before we are born, and we carry on with our lives from the dozens and dozens maybe hundreds of copies, facsimiles, from the contents contained within these memories. Especially the memories that trigger stimulus-response. I don’t care if Lisa Barrett agrees with stimulus-response, we act like we ‘react’ rather than respond to external stimuli when it reminds us of a past unresolved painful incident. Human beings ‘act’ like they are living life, obeying themselves as of the past, not present moments of fear, anger, grief, resentment, etc, not from a current constructed reality, but in response to a past event which can be traced and resolved. Without first studying the effects of memory traces, engrams all else is pointless. So I’m sitting in a group therapy session in the late 70’s and a persons says, why did you just smile it doesn’t seem appropriate for what this other person just said basically hinting that I am a phony, not being authentic, and I didn’t why at the time but now I would say, of course I’m a phony, not authentic, because I’m not operating from my own valence, my own personality, I’m operating from copies of painful memories which create false valences that have command value over my conscious mind.” We think we are living in our own personality, but few of us really are.

Hi David, sounds like these ‘memory traces’ would encompass the concept of emotions being innate (that is, our ancestors survived and reproduced better because they responded appropriately to challenges, including emotional responses)

Jeremy Griffith certainly thinks so. 2 million years ago he claims our ancestors lived in cooperation with one another, non-competitive-and nurturing but when humans became conscious over time our conscious mind conflicted with our natural instincts, maybe our innate emotions, and is why he claims we have become aggressive, UN-cooperative, competitive, angry, jealous, etc, which he calls the Human Condition. That is probably the worst summary of his thinking on this but but to take this a step further, it is not the instincts or our innate emotions that are aberrated, but because the brain/’conscious’ mind has fell victim to being overwhelmed with inaccurate sensory data. No one would ever suspect becoming ‘conscious ‘ would be a problem to human kind, or especially to our innate emotions and instincts, and there is only one reason it is. When we become injured, if sufficiently impacted enough, there goes the conscious mind, and so goes any logic, reason, rationality, gone or greatly reduced. The brains backup system seems to be the creation of a painful memory trace containing the exact of details of the injury. With the invention of language, words, phrases are also recorded so when Little Johnny is spanked, that’s one thing, but at the same time, if he is told ‘he will never learn,’ or will never amount to anything, then these words are taken at face value, internalized, and when the environment reminds Johnny, (sorry Johnny, he always gets it) of his spanking, he will likely also (have a reduction of consciousness) which allows the words and phrases to to rise to the surface and have command value over his conscious mind. In this way, we have a much more immediate problem then Jeremy Griffith realizes. Stimulus-response is the present Human Condition, in my opinion. But, I am not a biologists or psychologists, but a student of the mind, I’ve just had an intense interest in how the brain/mind works and this isn’t all original information from me, but an attempt to articulate the best I can for the average reader because I’m currently trying to write two books. The Crying Brain, and The Trial of the Human Brain. The Crying Brain because I have neurological impairment and confirmed brain damage from exposure to toxins in a past paint business and I realized, mentally I ‘feel’ and sense what my brain must be coping with as a damaged organ. And wondered why I’m getting these symptoms? To the brain is it damaged and cannot process sensory data and that drives my brain crazy. As an organ only capable of insuring survival for the human organism it is really frustrated that it can’t perform its duty. It is designed for survival, and can’t do anything else. It has caused me symptoms of mental illness and damage seems to be the least of its worries. It is more worried it can’t process sensory data accurately. It is almost like it knows the human organism’s isn’t functioning properly and unlike other organs in the body, it is because it has to also operate on accurate sensory data to compute optimum survival for the human organism and it isn’t able to do that. Call me mad, but I believe the brain needs accurate sensory data as much as it needs blood carrying oxygen and nutrients to be healthy. The Trial of the Human brain brings together some of the greatest minds in modern and past history via a time portal to speak about the brain, whether or not we have free-will, whether consciousness is a byproduct of the brain or is separate, etc and will have past Psychologists, and modern neuroscientist and moderated by Chat Gpt with me as the witness that questions both the prosecution and defense. I’m also able to respond to both. For too long our justice system have tried individuals, held them accountable, responsible for their actions, when we can easily see how the brains wiring controls individuals. It’s time to put the brain on trial because I think it is in control more that we realize at this stage of human development, but is also innocent. Capable of horrors and destruction beyond belief and also incredible art, beauty, love, compassion, the human brain is an organ in conflict with itself. Both fiction, satire, and truth, the Trial of the Human Brain will try to answer some of the most profound questions in human history.

I guess we’ll never know when the major changes in the human condition truly occurred, to me it seems that the big shift that truly messed us up occurred much more recently – when we went from being hunter-gatherers to doing agriculture. We tend to think of that as progress (the agricultural revolution!) but seems that our lives became more difficult and unpleasant when we made that transition.

And the industrial age, and now the technological age. Each shift an attempt to make our lives easier, more prosperous more fulfilling, but past human thought and behavior seems to follow us into the next shift, because humans seem to operate similarly to LLM’s- based on the evolution of past ‘patterns’ of thinking, internalized scripts, and something LLM’s don’t have, facsimiles, ‘copies’– recordings, imprints, mental image pictures of moments of unconsciousness-caused from UN-analyzed, UN-assessed sensory data, the gaps, missing pieces, left over from our past painful experiences because small and large traumas are ignored, or not processed correctly when they are addressed.

And yet each new generation, children and young adults seem almost immune to these effects until they get older, then they are repeating the same mantra, “change” “we need change” and those that have a degree of self-awareness will acknowledge “I need to change.” We keep living the same patterns over and over again. It’s a vicious cycle. What are we to do Dr. Westlund?

Epigenetic changes to occur, for sure, and certainly memes (and I mean Dawkin’s original version of it, not the type we’re seeing shared on social media) affect our behaviour as much as do genes… And to answer your last question, right now it seems to me that we need to protect democracy across the world and fight climate change… 😉

I’ve done it. I’ve closed the gap between Lisa Barrett’s theories on emotion (that they re responsible for all our thoughts, behaviors, actions, and Jeremy Griffiths theories on our past cooperative, non-competitive, nurturing instincts before and after the development of the conflict between the developing conscious mind and instincts beginning 2 million years ago resulting in aggressive, angry, competitive, non-cooperative non-nurturing (emotional states.)

The missing pieces.