Revised May 2024.

There are two important question to ask before teaching an animal a new skill.

In another blog post, I discussed the first question, one that is extremely basic but often overlooked: “what is the cost/benefit of the behaviour?” Is it useful, useless, abuse or an ethical dilemma?

Once a behaviour has been found to be useful, it’s time to consider how to best go about teaching it.

And this brings us to the second question.

Which is the best technique to teach the animal how to perform a new skill?

You know the old saying “All roads lead to Rome”..?

With regards to animal training, the same is true. There are many ways to teach animals what you want them to do.

Many ways to “get” behaviour, as it were.

Some trainers may say: “this is how you train your dog to sit.”

Or your horse to load in the trailer.

Or your parrot to step up.

Many novice trainers don’t realize that what their guru is teaching is but one way out of several.

And perhaps it’s the best way. The most efficient. The fastest. The one that facilitates future learning.

Or perhaps it’s not.

Perhaps it’s just what that particular trainer was taught. And that trainer’s predecessor. And so on.

What bothers me with this way of learning about animal training is not that inefficient techniques get maintained. That’s unfortunate, but not alarming.

To me, it’s the fact that unethical techniques get perpetuated that’s really disturbing.

Like the use of prong collars for dogs.

Doesn’t that look a bit like The Collar in “26 Medieval Torture Devices to Haunt Your Nightmares”?

Do I have a problem with this type of collar? Yes, I do.

Will I go on a rant? No, I won’t.

I’ll stay detached. Though I did write a blog post about the dangers of dog collars at one time.

So, I won’t rant.

For now. But beware of ranting below – I’ll give fair warning though.

Back to the prong collar. This device was designed to keep dogs from pulling on the leash. It accomplishes this by providing discomfort and pain when the leash is taut. So, pressure on the leash is uncomfortable or painful, and the dog will avoid it.

Actually, as long as he’s doing anything but pulling the leash taut, he should be “safe” – whatever prong collars feel like when pressure isn’t applied. Don’t know, I’ve never tried one of those – they’re forbidden in Sweden. But Grisha Stewart tested one in this video, and said that to her they were uncomfortable / painful even when there’s no pressure on them – and that the presence of fur probably wouldn’t reduce the discomfort.

On a walk, the dog might be behind, in front of, to the left or to the right of the person. As long as the person doesn’t jerk on the leash, all these positions would be equally acceptable to the dog – and the dog would have no further information about whether any of these positions would be preferable to the person walking the dog.

When the dog performs an undesired behaviour, something nasty happens, so the dog stops doing the unwanted behaviour in order to avoid the aversive stimulus. In other words, when the dog pulls on leash wearing a prong collar, the leash becomes taught, causing pain – so the dog stops pulling in order to avoid the pain.

That is actually the modern definition of punishment. In semi-technical terms, pulling is punished. In fully-technical terms, pulling is positively punished. Incidentally, walking-on-a-loose-leash is also negatively reinforced. More on this later.

Punishment is a useless way to get behaviour

Punishment is a lousy way to teach desired behaviour. By definition, it only teaches the animal what not to do – any number of different behaviours can stop the aversive stimulus. Punishment has a huge list of unwanted side effects too.

Do I have a problem with punishment? Yes, I do.

Will I go on a rant? No, not yet.

I’ll just drop this topic for today. Though I did write about the 20 problems with punishment here.

You want the dog to walk nicely by your side when you go for a walk?

You need to communicate this to your pooch.

Don’t use punishment when he doesn’t do what you want. As counterintuitive and strange as it may sound, “stop pulling” is not what you should be communicating.

Rather, reward him when he does what you want. “Walk next to me” is the message you want to convey.

To get desirable behaviour, we need to focus on reinforcement.

Wanna get behaviour? Use reinforcement!

There are several ways of getting behaviour through the process of reinforcement.

The key to reinforcement is giving the animal something he values – contingent on the desired behaviour. You reinforce when the criterion for that behaviour is met. He will then repeat that behaviour in order to get more of whatever you’re offering that’s valuable.

For instance, say you want your… cow-dog… to lie down on a towel.

Reward her for doing it –and she’ll do it more. This is what reinforcement is all about. It renders behaviour more forceful. Re-enforces it. Behaviour becomes stronger, more intense, more frequent.

Actually, technically, we’re not giving rewards, we’re giving reinforcers – because of the effect that reinforcers have on behaviour: the animal works to get more of them. Rewards may sometimes reinforce behaviour, but sometimes not.

If you’re not seeing behaviour change, you are, by definition, not using reinforcement.

OK, great – but let’s say that the cow-dog isn’t on the towel?

How do I get her there so I can reinforce her in the first place?

So, how do you get from what-you-have to what-you-want?

Actually, there are a bunch of different ways.

Again, don’t punish your cow-dog for not doing what you want. Rather, communicate what you want using one of the 7 techniques discussed below. As you’ll see, I like some better than others.

Seven ways of getting behaviour.

Generally, it’s important to choose a good, comfortable learning environment and set it up so that it’s easy for the animal to learn the intended response. Minimize distractions. Make sure there are no scary things around. Choose reinforcers carefully.

Below you’ll find an extremely condensed summary of how to use the main operant techniques. Some techniques work well in some contexts but not in others – and may be used in different ways than what’s described here. It’s beyond the scope of this blog post to go into the details, but I have an online course that does all that – and more..! 😉

Also, in this post I’m just discussing how to “get” the behaviour to the point of the animal offering it, not how to maintain it or put it on cue (more about how to teach cues here, though). That needs to be considered too…!

Shaping:

- Reinforce a response that the animal is already offering

- Behaviour will change as the animal tries to figure out exactly what earns reinforcement

- As behaviour changes, slowly shift the criteria towards responses resembling the goal behaviour

- Gradually stop reinforcing “old” responses

Targeting:

- Present the animal with an object (what animal trainers call a target)

- As the animal reaches out to investigate the target, reinforce

- Repeatedly reinforce the animal for touching the target in the same location

- Present the target in a new location (this is called generalization)

Luring:

- Show the animal food – slightly out of reach – the animal moves to eat it

- Repeat – present food slightly out of reach, allow the animal to move and eat

- Present and move the food item to move the animal in the direction that you want

- Beware of frustrating the animal by moving the food item too far without allowing access

- Gradually fade the lure so that the animal moves without seeing the food beforehand.

Scanning/Capturing:

- Observe your animal carefully (scanning)

- Don’t stare, which might be disconcerting

- When the animal just happens to perform the desired response, reinforce it (capturing)

- Wait for the animal to repeat the response that just earned reinforcement – reinforce again

Mimicking / Social learning:

- Cue another animal (the model) to perform a response that is familiar to both animals – in front of the learner. Reinforce. Then give the same cue to the learner – again, reinforce the response

- Ask the model for another response that’s familiar to both, then cueing the learner for the same one

- Cue and reinforce the model for performing a behaviour that’s familiar to him, but unfamiliar to the learner

- Give the unfamiliar cue to the learner and hope that he’s understood the game – reinforce it, even though it may look crappy initially. You’re reinforcing “copy your friend”, not just “perform the right response”

Moulding:

- Manually form the animals’ body into the position that you want, using for instance your hands

- If the animal likes body contact and relaxes into position, keep touching and stroking (positive reinforcement)

- If the animal dislikes body contact or is tense, remove your hands (negative reinforcement)

Releasing pressure (a type of negative reinforcement):

- Give the intended cue and give the animal a very gentle but firm static push (the “pressure”)

- As he starts to lean away from the pressure (technically this is called an escape response), release the pressure

- Keep giving the cue immediately before adding pressure

- Allow the animal time to respond to the cue without having to add the pressure (to get avoidance rather than escape)

The elephant in the room.

I know you’ve been waiting for it – and without further ado, here it is:

The Rant.

It covers the following section, and is a bit too technical for beginners, perhaps. Skip to the next section if you’re not consumed with curiosity.

I should warn you that when ranting I often revert to my scientific background rather than becoming foul-mouthed. So, expect 3-4 syllable words and bureaucratic, long-ish sentences.

Here we go.

I was hesitant whether to include pressure-release (a type of Negative reinforcement) on this list. It’s a problematic technique, but exceedingly commonly used – especially among non-trainers.

I could have just omitted it.

Instead, I chose to include it. Why?

- Negative reinforcement is arguably the most misunderstood term in the whole of psychology: the majority of animal trainers don’t even know how to define it. I have the data to back up that statement, in case you’re wondering (in my sample, 60% of trainers gave a faulty definition).

- It’s got a bad reputation so nobody hardly talks about it, or teaches how to do it properly.

- Negative reinforcement is often used unintentionally to get behaviour, so many animals are inadvertently exposed to it (hint: if your dog is on a leash, he has been exposed to negative reinforcement – regardless of whether he’s wearing a harness, a flat collar or a prong collar).

- I see negative reinforcement misused very badly to intentionally get desired behaviour – probably because of the prevailing ignorance.

- Many people don’t realize that negative reinforcement can in some cases preferentially be used (in conjunction with other procedures) to get rid of unwanted behaviour by giving increased distance to a trigger contingent on specific behaviours (CAT and BAT come to mind). This allows the animal to control the exposure to the aversive stimulus, and is often more effective and humane than the alternatives, even those involving positive reinforcement.

- Negative reinforcement is heavily stigmatized, so these highly specific and useful applications are not given a fraction of the attention they deserve.

And who is suffering because Negative Reinforcement isn’t discussed?

The animals, that’s who.

So, animals suffer, because animal trainers don’t teach about, or discuss, negative reinforcement.

Negative reinforcement is the elephant in the room.

It’s big, it’s awkward, it’s knocking over all kinds of furniture and expensive ornamental vases, and many trainers are looking the other way, saying “I only use Positive reinforcement – I wouldn’t ever stoop to that!!”

I agree that positive reinforcement is the best way of training animals, when the objective is getting desired behaviour.

But negative reinforcement is really useful and humane in a sub-set of contexts when we’re aiming to get rid of unwanted behaviour.

And – we don’t help animals by not talking about negative reinforcement.

I’d even go so far as to say that not discussing it is a disservice to animals, pet owners and animal professionals.

So, I think animal trainers have the obligation to discuss negative reinforcement training. At the very least so that people come to realize that they are perhaps unknowingly using it to get behaviour – and learn to minimize its potential harmful effects.

Here are my two major concerns (out of several) when seeing how negative reinforcement is commonly applied when attempting to get behaviour:

- People use way too aversive stimuli – frightening animals into a flight response rather than teaching them to move away from pressure. “Pressure” can be anything from gentle almost imperceptible touching, to presenting a toy crocodile at a distance, to shouting, waving arms, and spraying water. I see people unnecessarily going for the big guns right off the bat.

- People don’t remove the pressure when the animal starts responding. This implies potentially punishing the correct response.

Remind me, what term did I use, again, when discussing punishment of unwanted behaviour as a learning tool for teaching new behaviour? “Crappy” I think. “Lousy” comes to mind, too. Or perhaps it was “Inferior”?

That was when punishing the unwanted behaviour.

But punishing the correct behaviour?

That’s … Exasperating. Not to mention unnecessary and potentially abusive. One reason I’m ranting.

One reason animal trainers need to talk about Negative Reinforcement.

Incidentally, I teach about Negative Reinforcement in my Advanced Animal Training course, discussing both the problematic versions (typically inflicting negative emotional states on the animal, with all the potentially serious repercussions involved) as well as the under-used, humane applications (involving positive emotional states that lead to diametrically opposite effects, empowerment and resilience).

I’ll try to stop ranting now. After all, this is “7 ways of getting behaviour”, not “Pontificating about what Animal trainers should be teaching”.

Considerations when choosing technique

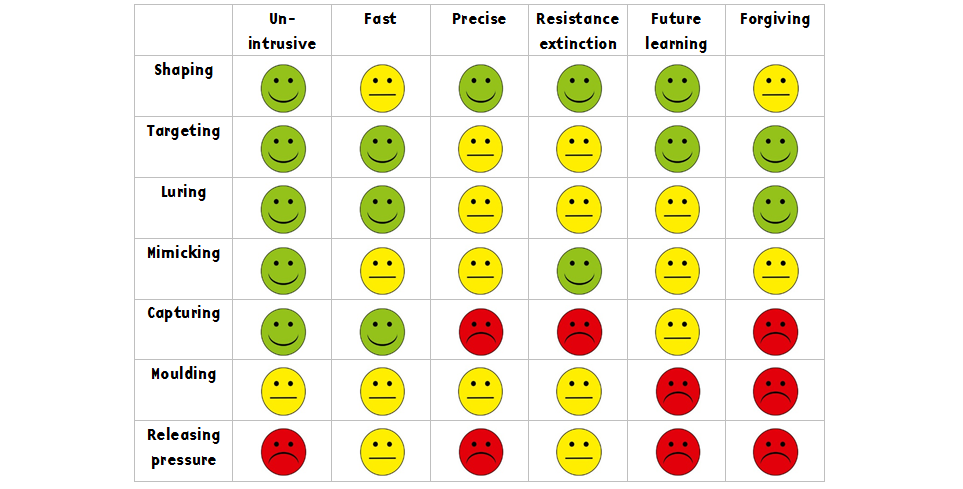

The road you choose when getting behaviour can be more or less:

- Un-intrusive. How much control does the animal have of the learning and performance? Does he have choices? Is the technique potentially aversive to the animal? Will it impact the quality of the relationship? This, to me, is the single most important factor when deciding what technique to use. I realize others may prioritize differently, though.

- Fast. How quickly does the animal become proficient when learning the behaviour? How many repetitions does it take until the goal behaviour is shown?

- Precise. If you were to take pictures of the animal performing the newly learned behaviour several times, to which degree would they be similar? How close to the final goal can you get using only that technique?

- Resist extinction. How quickly does the newly acquired goal behaviour fall apart if you for any reason can’t provide reinforcement?

- Future learning. Has the animal learned something that will make future learning, using the same or other techniques, easier? Is the animal savvier? Does he understand the “training game” – and is he willing to play it again?

- Forgiving. If you make a mistake during the initial training stages, will this slow down or muck up training this behaviour – or future behaviours? And what about your relationship with the animal, is it unaffected, improved or worsened through your choice of technique?

Skilled trainers often combine these techniques, thereby avoiding some of the downsides of using a single approach. In fact, the table below is probably completely useless to a skilled animal trainer, because they generally don’t perform the “pure” versions of these training techniques. They mix and match. Also, one hallmark of a skilled trainer is flexibility: the mix of techniques will depend on circumstance.

For a beginner, though, combining these techniques might be difficult, and it’s useful to know how they compare when using “pure” versions of basic techniques. So, if you’re serious about learning about animal training, I recommend that you master these techniques – and become mindful about the contexts in which they might be useful. This blog post doesn’t cover even half of it, but it’s a starting point.

As seen below, there are many reasons to gear your training to positive reinforcement.

I’ve been debating with myself whether I should actually include this table, since the little happy and grumpy faces imply that there’s solid data behind these.

There’s not.

What’s even worse, I am biased – so I’ve likely been unjustly harsh on methods that I dislike or am less familiar with. Also, a skilled trainer may use these techniques in a way that tweaks a certain procedure so it’s actually better than portrayed here. And an unexperienced trainer may do the opposite.

But I really liked the idea of smiley faces illustrating this concept – so I included it anyway.

Ha!

That’s the perks of publishing on a private blog rather than in a scientific, peer-reviewed journal. Not only can I go off on a rant, but I also don’t have to back up every single one of the smiley faces with data.

I can be speculative.

But.

Regardless of whether the smiley faces all have the right colour, or even if we should make these relative comparisons at all, the intended take-home message of this blog post is really to look at how your choice of training technique affects your animal, his learning journey and your relationship, given the place you’re currently at.

Look at the animal in front of you and try to determine how he feels about your chosen procedure.

Keep in mind that other factors will also influence how useful the chosen technique is, such as:

- Your skill level with each technique.

- The species you’re working with.

- The animal’s prior learning.

- How well you set up the environment before starting (the presence of distractors and aversives might affect certain procedures more than others, for instance)

- The complexity of the behaviour you’re training.

- Your timing.

- The value of the reinforcers.

- Where reinforcers are delivered.

- The interval between repetitions.

- And so on…

Still, I’m arguing that irrespective of these other influential factors, there are some innate differences in how these techniques tap into the animal’s learning mechanisms. All else being equal, outcomes should be slightly different if you’re going with just ONE technique.

Which road will you take – and how can you shift it towards “greener smiley faces”? Let us know in the comment’s section, below!

If you found this intriguing, I explain in detail all these seven techniques, including video examples of multiple species of animals, in the Getting Behaviour course. For more information about my online courses about animal emotions, learning and welfare, just sign up below! I’ll also keep you posted on free webinars and Masterclasses, new blog posts and silly experiments.

Reading list:

Fugazza et al. (2015). Social learning in dog training: The effectiveness of the Do as I do method compared to shaping/clicker training.

Hendriksen et al. (2011). Trailer-loading of horses: Is there a difference between positive and negative reinforcement concerning effectiveness and stress-related signs?

Innes & McBride (2008). Negative versus positive reinforcement: an evaluation of training strategies for rehabilitated horses.

Santos (2009). Limitations of Prompt-Based Training.

Sdao (2008): Advanced Clicker Training (DVD).

Zeligs (2014): Animal Training 101.

37 replies on “7 ways to get behaviour”

Found this training very informative as we come to terms with owning an 11 month old Springer Spaniel . We have struggled with such a high drive dog and it’s very good to start to understand how the dog thinks and the techniques to use. We have used a dog trainer but didn’t seem to make much progress as I think the trainer struggled to understand the dog but also failed to explain to us the what, why and how so we could understand what we were trying to achieve.

Was interested to see the use of targeting with a horse to help get them into its horse trailer. Our Springer hates going in the car, initially would be sick but now resists going anywhere near the car pulling backwards on the lead, real fear emotion.

Question – would targeting be a good approach to help get her into the car ? Using the targeting with positive reinforcement and fun emotion to combat the fear emotion ? Any tips how to help make her happier/less anxious in the Care always welcomed.

Great training, thanks.

Targeting is very useful to help move animals through challenging environments. There’s one caveat though – that the challenging environment becomes too challenging, so there’s essentially a conflict, or the animal suddenly realizes he’s in way over her head. In other words: that challenge needs to be introduced very gradually, and a close eye paid to the animal’s reaction..! 🙂

Thanks Karolina, understand. I think the fear our dog has of the car is deep and perhaps irrational now. I understand the slow approach is the correct approach but I fear we will have a need to take her out in the car before we ever get her ‘happy’ in the car, this undoing any work we do. I appreciate desensitisation or immersion is not a process to be entered into lightly but to be honest I don’t believe we will ever get there with a more positive approach. Will give it our best shot before we have no other choice. Thanks.

Can you provide the source about the origin of the prong collar? I’ve heard that it was invented for another reason, that is to stimulate dogs’ agression in defence training (as it feels like being bitten) and afterwards adapted for other reasons, including loose leash walkig. But I wasn’t able to find resources to prove any of these theses only the name of the guy who patented it.

Sorry, no. That may have been the starting point, but from my perspective the reason why it’s sold today is that it causes pain, and thus can be used to change behaviour.

Thanks so much for this Karolina and everybody else who have shared here.

I was gratified to read that it appears i do actually use a mixture of methods. Both with horses and dogs….no one size fits all…in my experience.

It absolutely depends upon the creature how i go about achieving the desired behaviour…this can change for different behaviours within the same creature …flexibility and imagination used with compassion and understanding. Honestly…children…dogs and horses..I use similar principles for all.

I think the mixed approach is by far the most common – but it looks different for each trainer! 🙂

I love your example about the horse kicking the gate to demand more apples. I gues one would call this “Demand Kicking.” I’m a dog trainer but it’s very interesting to read about training horses using positive reinforcement.

My dog is absolutely attached to his “pillow” because of frequent positive reinforcement there. I have to be oh so careful NOT to give into [infrequent] demand barking while he is on his pillow. He’s so stinking cute! I keep saying to myself ” Don’t do it or you’re going to create a monster.”

As for the primary article it was a great refresher of my ABC training. I use capturing for simple stationary behaviors e.g. capturing a dog who is sitting, standing, or down. It’s a great technique to “get the ball rolling” and keeping things friendly and positive.

glad you found this useful! 🙂

I think moulding is a lost opportunity in building a cooperative relationship and keeping all learning a fun game for the dog that is choice driven. Speed and precision are not important to me. Future learning is very important to me as I hope learning enriches the dog’s life with their person.

[…] understands the task (this would involve criteria setting, good timing, and being familiar with the seven ways of getting behaviour, and successfully teaching cues, for […]

[…] 7 ways to get behaviour […]

[…] really considering the Ethics of Animal Training: if there are several ways of getting behaviour, which should you choose? How will this choice impact current and future behaviour, the quality of the relationship, and the […]

[…] method of training is used? How are you getting behaviour? Are you choosing techniques that give control to the animal, that are unintrusive and […]

Just for fun, here is video showing an example of luring behaviors: https://youtu.be/ppcS6E9hVqc

Happy New Year!

Luring indeed… I would be very concerned with frustration-induced RAGE or the animal giving up altogether: it seems from the film that the animal doesn’t get reinforced too often…!

My understand is:

Positive reinforcement is adding something pleasant to encourage an animal to increase a behavior. (Treating a dog for sitting on cue.)

Negative reinforcement is removing something aversive to encourage an animal to increase a behavior. (Moving forward after stopping when a dog ceases pulling on leash.)

Postitive punishment is adding something unpleasant to encourage an animal to decrease a behavior. (Squirting a dog with water to stop it from barking–I present this as an example, not something I advocate!)

Negative punishment is removing something pleasant to encourage an animal to decrease a behavior. (Stopping play when a puppy bites to help extinguish biting behavior.)

By far, I find that negative reinforcement is the most difficult of the four quadrants to define.

I look forward to the remainder of the reading resources.

Loved it! Thank you for these interesting blogs 🙂

Glad to hear it! You’re welcome!

[…] Let’s look at the first of those two questions, as it will help decide whether a behaviour should be trained at all, and identify potential problems. I’m saving the second question for another blog post. […]

I loved this article, particular the photo-essay part, and I reviewed it on my blog: http://synalia.com/2016/09/20/4008/

Best wishes,

Kayce Cover

Kayce, how exciting! Thank you for taking the time to dive into this post – will leave a few comments on your blog!

[…] original article here, by Karolina Westlund, […]

Very interesting. I train dogs and horses and offer a few thoughts as churn this over all the time to make sure I can explain why I do what I do 🙂

1. I am completely “positive re=inforcement” with dogs. I use food, toys, etc, etc. I try to focus on the relationship rather than a series of commands and am moving further and further away from ‘obedience’ modes the more experience and learning that I get.

2. With horse I am a mixture of negative and positive. For example – I use a Monty Roberts Dually halter for encouraging horses to walk with me and not use flight. As you say, is the level of pressure that is important – I use the very least pressure and the horses respond quickly and I release pressure quickly – better still THE HORSE releases the pressure. I use pressure without touch – if I look at horses in the eye it says “go away” – that is pressure; If I look to the floor and turn away it says “follow me”.never ever do I inflict any pressure or any animal that can cause the slightest pain. If the flight response is too high the horse is not learning anything, only confirming his fear. To encourage the horses to come onto the yard without me having to fetch them (very useful when it’s cold and wet!) I reward their presence on the yard with apples thrown on the floor (I don’t hand feed). Once they learnt this (they did so very quickly) I followed the intermittent schedule of reinforcement principles and do not respond to any ‘demand’ for apples (e.g. kicking the gate!)

I have spent a long time considering whether it is different for prey and predators and I am of the opinion that it is but I am always open to having my views changed as more research and knowledge comes out. Why is it different? Well so as not to take up any more space I will say it simply but please understand that my explanation has many facets and nuances to it. However, on a simple level, dogs are pre-disposed to a reward system – chase food, eat it (the food does not come to the dog; only when it’s given by humans). Further, they have evolved like no other animal to be bonded to humans in a unique way to the point of dependence on humans for their survival . Horse have to LEARN a food reward system. They have also retained much of their innate survival instincts and despite the domestication process they have not evolved to ‘need’ humans in the same way. They are grazers, the food is just there they only have to walk around and get it. Teaching horses how to accept food as a reward from the hand (before they begin any training of behaviour/skills etc.) is the very big part that many horse owners/trainers miss out or do not do thoroughly enough and then wonder why they get bitten/mugged/hurt). It changes the fundamental nature of the horses processes. There is another aspect that I am exploring. Horses learn very quickly what is ‘pressure’/predatory and what is not – they have to in order to survive; if they kept on running they would die. This means that using this natural process is quicker but without compromising ethics or dignity whereas teaching some aspects by shaping techniques puts repeated stress and pressure on a horse for extended periods of time. A typical example: I wanted to teach my horse to go up some steps – we have a strong relationship; he did not want to go; I could have spent hours shaping etc. but I went up the stairs first, very slight pressure on his halter, he decided that I had ‘shown’ him it was safe and he wanted to release the pressure he went up the stairs – it took less than one minute. I feel it’s vital as you have so brilliantly explained to have a whole range of methods to ‘draw’ on depending on the need to the animal rather than the need of the human. Sorry, I’ve rambled on longer than I intended!

Dear Vicci,

Thanks for sharing your perspective! Interesting observation you’re making about predators and prey. I think you make an important point: they are differently wired when it comes to how vigilant they are, how responsive to potential threats..! Didn’t realize that horse trainers had a hard time teaching horses to work for food – that’s intriguing.

What a lovely blog post. And great table with training methods analysis. I keep thinking about the last column – forgiving.

I’ve seen many animals who are a living proof that pressure release, even if applied timely, is an unforgiving method, at least when it is the dominant training method. But would you say the degree of ‘unforgiveness’ of this method varies among animal species, or is it rather an individual thing?

Ewa, so glad you liked it – and I added that column last, as it occurred to me when I was preparing this post. But I agree – it’s very important!

Interesting question – I would expect that certain species would be more forgiving than others. For instance, it’s very often used with prey animals – and misused. As in: easy to trigger a flight response. I would expect predatory species to be less affected by pressure release training – but perhaps more risky too: easier to trigger a fight response.

Big individual differences too, some individuals would be easily sensitized by that approach to training, others not.

One thing I see a lot with negative reinforcement is simply that people see the word “negative” and assume it means “bad” when really in terms of the Skinner grid it’s a purely technical term. It often seems to conjure a very strong emotional response purely to the words.

My experience is different from a lot of people because I train horses and over the last ten years or so I have gone out of my way to learn with some of the best trainers in the world. One thing they all have in common is that the training starts from negative reinforcement and that combining it with very refined timing and understanding of how horses feel about the world you can fairly quickly get to a point where horses are comfortable and relaxed in their lives- it often affects the way they feel about the world when they aren’t interacting with humans. There is also a degree of subtlety available with horses that means once you have established a relationship with one you are unlikely to need to think much in terms of reinforcement most of the time- it becomes something more like a conversation, albeit an entirely non-verbal one. If anything that is where things get interesting for me.

Obviously different animals respond in different ways – I doubt what I know about horses would transfer well to many other animals – and with all techniques there are probably only a handful of people who are dedicated enough to have mastered them to an outstanding degree, but I thought this perspective might be interesting to you.

Ben, thank you so much for sharing – that sounds really interesting! I agree that a lot of animal trainers get very emotional when the subject of Negative Reinforcement pops up. Unfortunately, so many people use it in ways that are unnecessarily harsh on the animal – or don’t even know what they’re doing. Glad to hear that you’ve been exposed to so many good examples.

As always, complexity made simple, thus powerful. Shared with gratitude.

Claire, thank you – glad you liked it! 🙂

I found your chart very interesting! Could you say a little about the red faces under capturing for precision and resistance to extinction? It seems like since the behaviors we capture are behaviors the animal already performs, as opposed to, for instance, performing weaves in agility, that they would be very resilient in the face of extinction. But even putting aside the nature of the behavior, why would the capturing yield poor resistance to extinction? The capturing part is only the very beginning of the training, after which we reinforce the behavior like any other.

I also don’t understand about precision–capturing is one of the few times I use a clicker and I’ve gotten extremely precise behaviors that way. You have trained lots more animals than I have though, so am interested to hear your experience and reasoning.

Hi Eileen – great questions!

OK, here’s my reasoning: Capturing implies pinpointing a moving target. Depending on how quickly the animal is moving and how often the behaviour is repeated, chances are that the “captured” response will be a crude version of what you really want (in reality often a starting point for future shaping) – but a skilled trainer may have exquisit timing… So, from that perspective the response would typically be imprecise – though the animal might repeat it faithfully at that same criterion if you’re lucky. When you got really precise behaviours when capturing, did you do a little shaping, or was the behaviour perfect at once? 🙂

I agree that once established, captured behaviour would be resistant. But after the very first reinforcement it’s typically not. If the animal wasn’t paying attention, not in “training mode” or didn’t fully understand what was being reinforced, chances are that you won’t get the opportunity of a second reinforcement even if your timing was excellent the first time around. So, in these early phases of training, the response has no reinforcement history and is thus sensitive to extinction. Once repeated, reinforcement history builds and all that changes.

An excellent enjoyable and thought provoking blog.

thanks! 🙂

Oh- did I ever enjoy this piece!! My friend, Ann has taught me the values of +R training- dogs, donkeys, mules…even my 15 year-old cat has learned a thing or two! In a way, it’s the way we (should) teach our children…”wow- what a great job!” followed by a happy face, a treat- wouldn’t we all do more for these rewards? Food, praise, attention…I know my dog thrives on “good boy” and extra-exhuberant rubs. Will be passing this along. Thank you.

Glad you liked it, Pamela – and you’re absolutely right: this is how we all prefer to learn! 🙂