Revised February 2023 – original written in 2016 .

Recently there was a video post in my Facebook feed that caught my attention.

Typically, on Facebook, I’m a bit of a lurker. I’m not very active, and when I do watch videos I often don’t share, like or comment – even when perhaps I should.

This time, I watched, feeling my jaw gradually dropping in disbelief, and then I actually left a comment.

I wrote:

“I’m speechless”.

And that was it.

I know, kinda lame.

But I didn’t have time for an essay, and then I was flooded by the rest of the FB flow, so the film slipped to the back of my mind – where it’s been festering.

A few weeks ago, I wrote that I was speechless. But in the time that’s gone by, I’ve realized that I should do the opposite.

I should speak up.

I figure, if people don’t realize that using punishment in animal training has the potential of being extremely problematic, they need to be informed.

Jump straight to the 20 problems.

I am by no means the first to voice my concerns, but this obviously needs repeating.

The video I watched proposed an automatic correction feature of an “on-collar training and tracking device” for dogs. Apparently, it’s a thing that you attach to a collar that can track your dog’s activity and also deliver electrical stimulation (a euphemism for shocks), noise or vibrations.

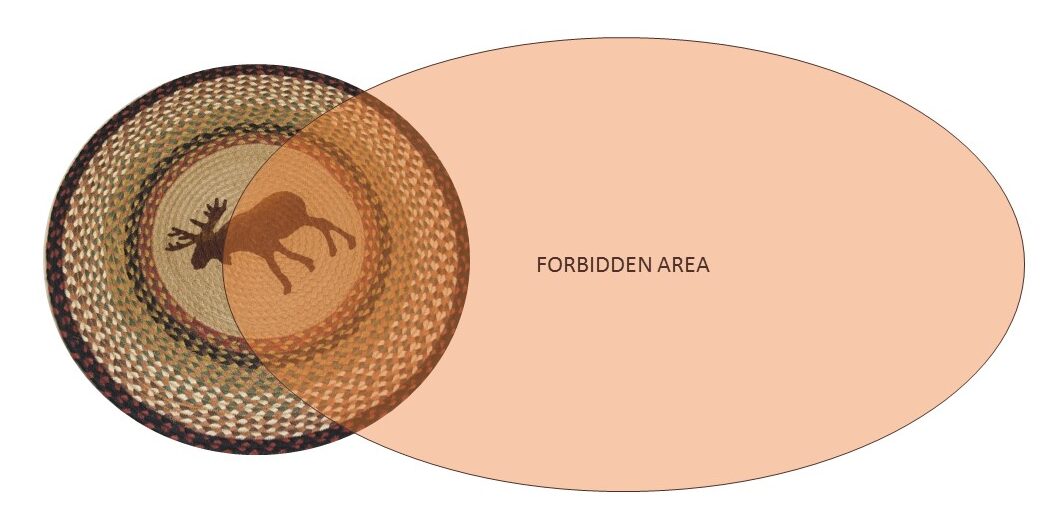

What was suggested in the film was that when the dog does anything that we don’t like, such as barking or trespassing in forbidden areas, it can be zapped, automatically, without us even being present. And so the dog would stop barking or trespassing, allegedly.

In the ad, this was referred to as the New Standard of Dog Training.

For me, it’s Completely Outdated Not to Mention Potentially Harmful.

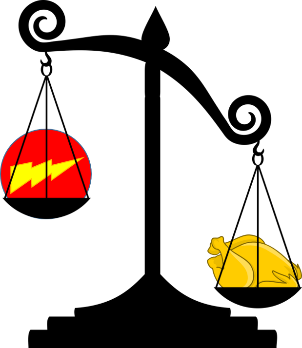

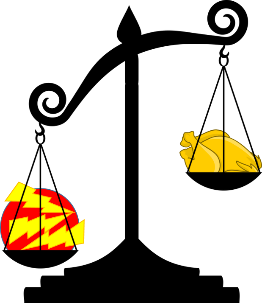

The thing is, punishment works – unwanted behaviour is eliminated. At least sometimes. So people keep using punishment.

But, here’s another thing.

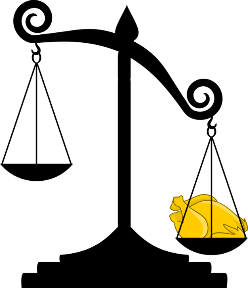

There is a price to be paid for using punishment. It may be a very small price, almost imperceptible. Or it may be very large.

It is the potential for serious fallout that worries me.

Using punishment in animal training is the equivalent to taking medication that only works sometimes and has humongous, not to mention common, side effects.

And if you’ve ever read the little well-folded leaflet that comes along with your prescription medication, you’ll know that some side effects are common, affecting almost everyone, and some are extremely rare.

Some are benign, and some are excruciating or even lethal, ranging from dry mouth to kidney failure, perhaps.

And often, those side effects are like Russian roulette, you never know whether you’re in for black urine (Flagyl) or serious birth defects in your unborn child (Thalidomid).

Frankly, I wouldn’t risk it unless there were no other option.

At the very least, people should be aware that there are potentially serious side effects, rather than stumbling blindly into a punishment scenario.

Also, people should be aware of the alternatives, so that they can make an informed choice.

And yes, in a way I’m living under a rock. I’m not a dog owner, and such gadgets are not allowed in Sweden. I realize that in many other places they’re the norm, and nobody raises an eyebrow, let alone drops a jaw.

Perspective shift

Let’s take the animal’s perspective for a minute.

Imagine you’re a dog.

Come on now. I know you want to.

Medium-sized, brown, long hair. Goofy ears. Not being a dog persion, I’m unfamiliar with the different breeds, but the dog that’s in my mind’s eye looks sort of like Lady in that old Disney film. You know the one.

Imagine Lady’s standing on the doorstep to the kitchen, and there’s a chicken on the counter, as depicted in the video that caused the jaw-dropping.

The smell is delicious. And it’s within reach, too.

OK Karolina, but why are we doing this?

Bear with me. We’re imagining that we’re Lady so that we can get an understanding of her:

- Conflicting motivations

- Learning experience when zapped

Below you’ll find two main sections:

- The 20 potential problems with punishment.

- A few suggestions of how to get rid of counter surfing without resorting to punishment.

This is a long blog post, and in case you want to return to it later, it’s also available as an e-book. Just click the button below, and I’ll see to it that you get it! I’ll also keep you posted on future blog posts, silly experiments, free webinars and Masterclasses as well as when my full online courses are open for admission. Oh, and you’ll get the infographic, too..!

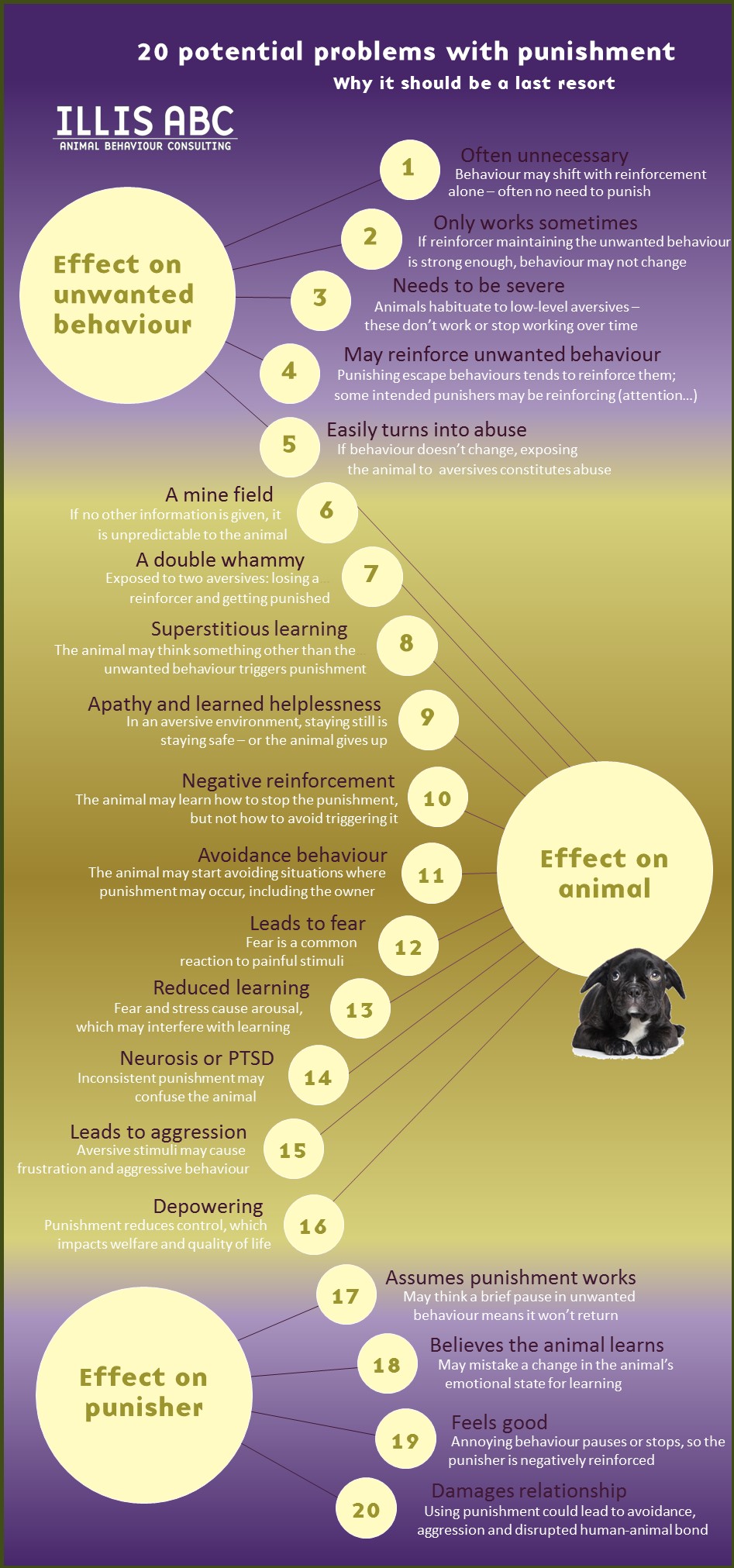

The 20 problems with punishment

If no other information is available to the animal, such as being fitted with a remote electronic collar, these are the potential problems that have been identified when using punishment to stop unwanted behaviour.

Effect on unwanted behaviour.

1. Punishment is often unnecessary.

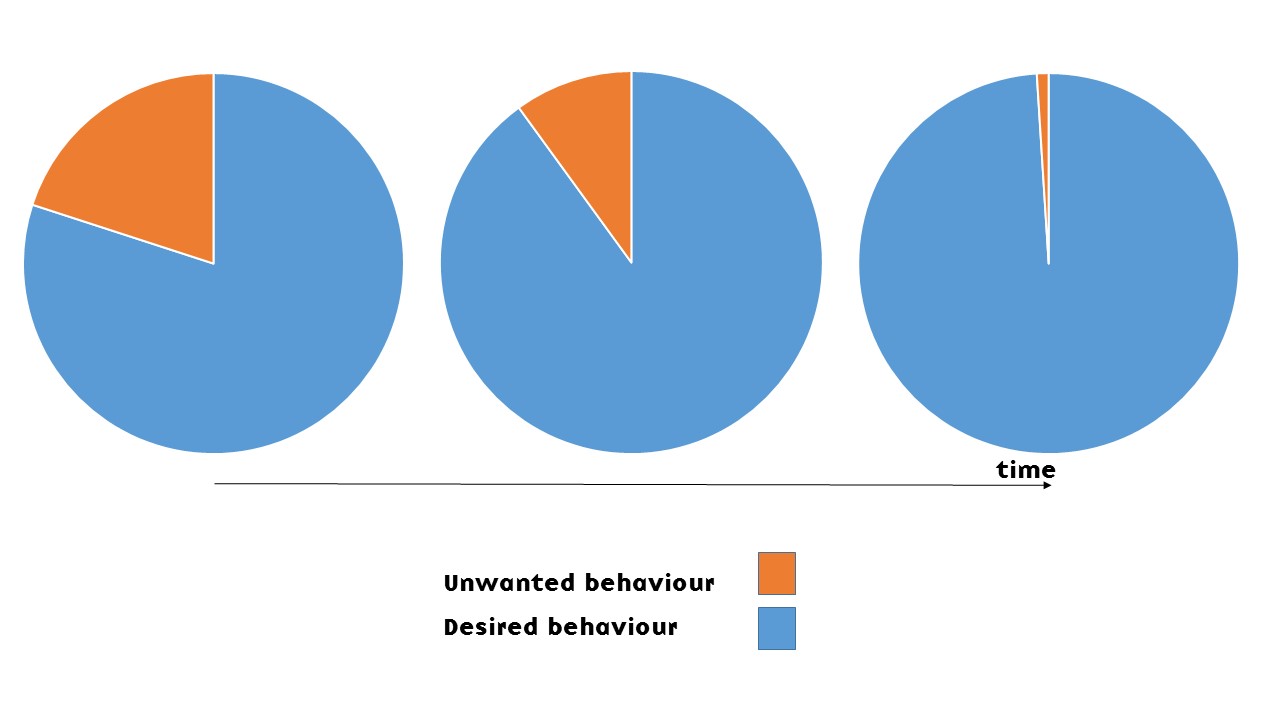

There’s this misconception amongst some trainers that to get desired behaviour, we use reinforcement, and to get rid of undesired behaviour, we need to use punishment.

That’s a misunderstanding.

The animal can only perform so many behaviours, as there are but 60 seconds to a minute. If one behaviour increases, then by default, something else needs to decrease – whether that’s resting, running, doing unwanted behaviour – or something else.

In fact, this phenomenon is often where the solution to unwanted behaviour lies – as discussed in the last section of this blog post. Punishment is often unnecessary – reinforce something else and the unwanted behaviour might diminish, especially if what you reinforce is incompatible with the unwanted behaviour. The choice of which behaviour to reinforce is important, since some behaviours are likely to be affected by certain others – and others aren’t. Incidentally, I discuss this in great detail in my Resolving Challenging Behaviour course.

2. Punishment only works sometimes.

One situation where punishment is often very ineffective is when the unwanted behaviour has become an established habit. Animals behave for effect, at least initially. At first, Lady may have started counter surfing because she found interesting things to chew on in that location, so the behaviour was maintained by the consequences of finding the forbidden food. She learned “when-I-enter-the-kitchen-I-jump-up-on-the-counter-and-find-interesting-things-to-eat”. And what we know about habit formation is that over time, behaviour tends to shift from being more or less consequence-driven to being more or less cue-driven. So in Lady’s mind, as the behaviour becomes habitual, it’s turned into “when-I-go-into-the-kitchen-I-jump-up-on-the-counter”. So she’s not so much jumping up on the counter to get the chicken, she does it because that’s simply something you do when you’re in the kitchen, without conscious thought – in this context, the counter-surfing has morphed into being on autopilot. Which means that established habits can be 1) really hard to change, and 2) punishment is often now quite ineffective, since punishment is a consequence, and consequences are no longer what’s driving the behaviour.

But animals don’t always perform behaviour out of the blue, on autopilot – and certainly not the first few times! If Lady is barking, we can assume that she’s got a reason to do it. And if we’re leaving a chicken on the counter, we’re asking for trouble.

So, unless the behaviour is habitual, we can assume that animals do behave for effect. For instance, Lady may bark so that the scary person goes away (negative reinforcement). Or Lady may steal the chicken because it smelled darn good and tasted even better (positive reinforcement).

The thing is, reinforcers maintain behaviour. Having found a chicken on one lucky occasion, she will likely steal the next chicken too if there’s an opportunity. Lady will start counter surfing, looking for tidbits. The counter has become interesting. The behaviour is consequence-driven.

Which means that when you’re introducing punishment into the equation, it’s a consequence competing with the available reinforcers – whatever they might be. In turn, this means that unless the punishment is annoying enough, the delicious chicken may trump being zapped.

Lo and behold. Lady may choose to steal despite being zapped.

What does this mean?

It means that sometimes, punishment doesn’t work, even when the behaviour is still consequence-driven.

What have we accomplished here? We’ve caused Lady discomfort, yet taught nothing that’s useful to us. She’s stolen the chicken and gotten a bit used to aversive things happening – which incidentally leads straight to one of the other problems, discussed below.

Regardless of the intentions, that actually qualifies as abuse in my book – as I discuss in this blog post. I’m defining abuse as anything that causes suffering to the animal and has no benefits to the trainer. The abuse may be mild or severe depending on how unpleasant the zapping is.

At that point, many people increase the level of zapping.

At some intensity level, the zapping will likely be annoying or painful enough to actually discourage going for the chicken.

Do you see why this is a problem?

In order for punishment to actually work it needs to be severe enough.

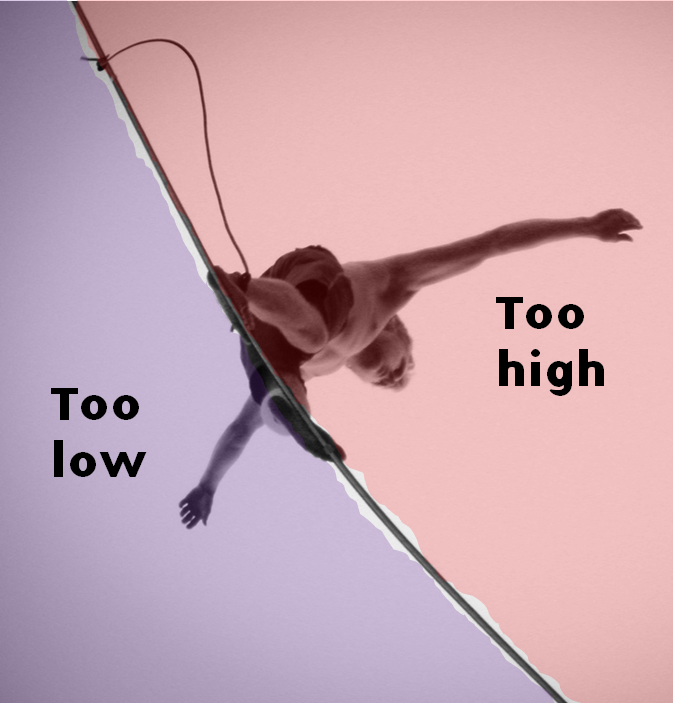

3. In order to work, punishment needs to be severe.

How much is “severe enough”?

Level 3 on some scale? Or level 7 perhaps? Level 42?

How do we know?

One major problem of punishment is that we can never know how much is enough to trump the available reinforcers, and how much is too much.

Using punishment is like walking a tightrope. Staying balanced on the rope is the equivalent of effective punishment that diminishes the target behaviour.

But there are two ways of falling off the tightrope, and the path is very narrow.

- Too low intensity – and we’re being abusive: causing suffering without the animal changing her behaviour.

- Too high intensity – and we’re also causing Lady needless suffering – she would have changed her behaviour even at a lower level of intensity.

To make it even more difficult, this balance of available reinforcers and intensity of punishers will look different for each scenario – it’s a moving target! Chicken might be very popular and warrant a huge zap, whereas yesterday’s cheese sandwich only requires a small one. A hungry Lady may make another decision than a full one. She may make another decision in the kitchen than in the living room. Or depending on whether anyone’s present or not.

When the cat’s away the mice will play. Which takes us straight back to “punishment only works sometimes”.

4. Intended punishment may reinforce behaviour.

Say that Lady vocalizes out of fear and gets zapped. Unexpected or intense zapping often leads to fear, so fear-related behaviours increase.

Hence, Lady vocalizes more, rather than less.

Whenever fear is involved, we risk that intended punishment increases that fear and leads to more fear-related behaviour, some of which may be annoying to us. Attempting to punish such annoying behaviour would then be entering a vicious circle.

And the problem of course is that it’s hard to predict whether the animal will find the zapping unexpected or not: scientific studies have shown that if the animal learns under which circumstances zapping occurs, he’s less likely to become fearful and stressed (1).

Another example of punishment inadvertently reinforcing the unwanted behaviour: Lady vocalizes, and gets scolded. This negative attention is intended as punishment, but attention happens to be reinforcing to Lady, so vocalizations increase.

Often we don’t realize what’s reinforcing to animals – or children for that matter.

I see this so often in misbehaving children. They’ll do anything to get their parent’s attention – even when it’s getting yelled at. “no, stop that, don’t do that, I told you a thousand times…!!!”.

Which brings us to the third example.

Don’t think of a yellow car.

No, I said don’t!!!

You didn’t think of a yellow car, now did you? I told you not to!!!

You’ll get one more chance. Don’t think of a red car.

What!!! Again!!!! I thought I made myself very clear…?

This phenomenon is called the ironic process theory and it suggests that when we focus our attention on unwanted behaviour, we tend to perform them. A practical example might be “I’m not going to do any shopping today” – and then you end up buying a lot of stuff you don’t need. This example may not be so useful when discussing animal training, but certainly when raising kids.

“Stop hitting your brother!!!” could be rephrased as “try talking to him instead” to avoid the risk of accidentally reinforcing the unwanted behaviour.

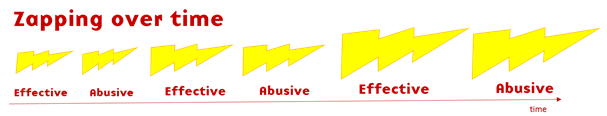

5. Abuse often becomes part of punishment regimes.

Back to counter surfing and dogs.

Set the zapping level once and be done?

Mostly, not.

Often, we can’t calibrate the intensity of the aversive stimulus for a particular context once and be done. There’s a phenomenon referred to as “Punishment callous” – Lady may build resistance to the punishers; she may habituate, or desensitize, to aversives. After a while they might not work any longer, so the trainer has to increase the level of zapping in order to retain effectiveness. And then the higher level stops working too. So we’re back at abuse, only we’re now causing much more discomfort or pain than originally (2).

Punishment easily becomes a vicious circle, ranging from too much, then becoming effective, then abusive, as the frustrated trainer tries to find the zap level that “works” – and all the while the intensity of the zapping is increased.

I realize that not all punishment scenarios look like this, but it’s plausible that some do. And since I’m discussing techniques that could potentially harm animals, we need to discuss the worst case scenarios rather than effective punishment with a minimum exposure to aversives.

My concern is the potential for harm these techniques and gadgets could cause in the hands of unexperienced trainers and pet owners.

Sounds like “the New Standard of Dog Training”?

Leaving a chicken on the counter. Perhaps slipping into the vicious circle of increased zapping.

To me, that is setting Lady up to fail, and then abusing her for doing so.

Punishment can be delivered in a way that reduces the risk of falling into the vicious circle of abuse. But I’m not going to discuss how it’s done in this blog post.

Why? Because I sort of get queasy just thinking about it, I would only use it as a last resort, and I don’t think anyone should use punishment without being aware of all the possible ways that things could go wrong.

Let’s move on to how being exposed to punishment could potentially impact Lady.

Effects of punishment on the animal

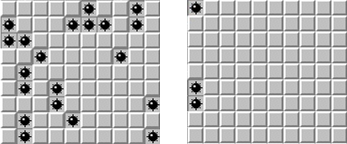

6. Being punished is like walking a mine field.

Back to being Lady.

Imagine scampering into the kitchen, following a delicious scent. And suddenly, out of the blue – zap!

You startle and take a step back. Move sideways. Zap!

Step to the left. Zap!

Step to the right. Oh, that was safe. One more step. One more. Zap!

Zap!

Zap!

Zap!

See what I’m getting at?

When punishment is first introduced, Lady has no clue what’s going on. For her, it’s like moving across a mine field. Sometimes you get zapped, other times not.

This raises some interesting questions.

What is the density of “mines”? How many ways of doing wrong are there? Are there any safe “areas”? Are there any warning signs?

How will she learn to navigate the mine field?

The distribution and intensity of the zapping will have profound effects on how well the animal learns what’s going on, and her subsequent behaviour, as we’ll see below.

Punishment doesn’t tell the animal what to do. With no further information, all the animal can do is try to avoid the mines.

Again, unpredictable shock is stressful (1). If the mines seem completely random to Lady, learning will not occur – and she will become stressed.

7. Punishment is a double whammy.

Yesterday, Lady was stealing chickens – counter surfing was being reinforced.

Now she’s being zapped instead – plus she’s no longer getting any reinforcement.

That’s not one aversive experience – it’s two.

A double whammy, as it were.

8. Punishment could lead to superstitious behaviour.

Let’s say that Lady was doing several things when the zap occurred.

As in, putting the foot on a kitchen rug at the same time as walking into the forbidden zone in the kitchen.

So, Lady got zapped for trespassing into the zone, but what was most obvious to her was the change in texture underfoot. Lady could start to associate zapping with the stepping on the rug. So she might start avoiding the rug – which may have completely different dimensions than the forbidden zone.

She might think she’s solved the problem. Avoid the rug – avoid being zapped!

So we’ve unintentionally punished Lady for something other than the unwanted behaviour. She might not have learned anything about the perimeters of the forbidden zone, but she is now avoiding the rug.

9. Punishment may lead to apathy/learned helplessness.

Another solution, for many animals, is not doing anything. If moving results in seemingly random zapping, then there’s safety in staying still.

Some animals that are routinely punished will not volunteer many behaviours; we risk that they becoming apathetic.

In the face of inescapable shocks, Lady might slip into a serious stress syndrome called learned helplessness, related to clinical depression (3). Lady may stop even trying to avoid being zapped.

And one problem with an animal in a state of learned helplessness is that the animal isn’t actually doing much of anything. To the untrained eye, the animal may even seem relaxed.

And also, of course, this general suppression of all behaviours might include behaviours that could potentially be of interest.

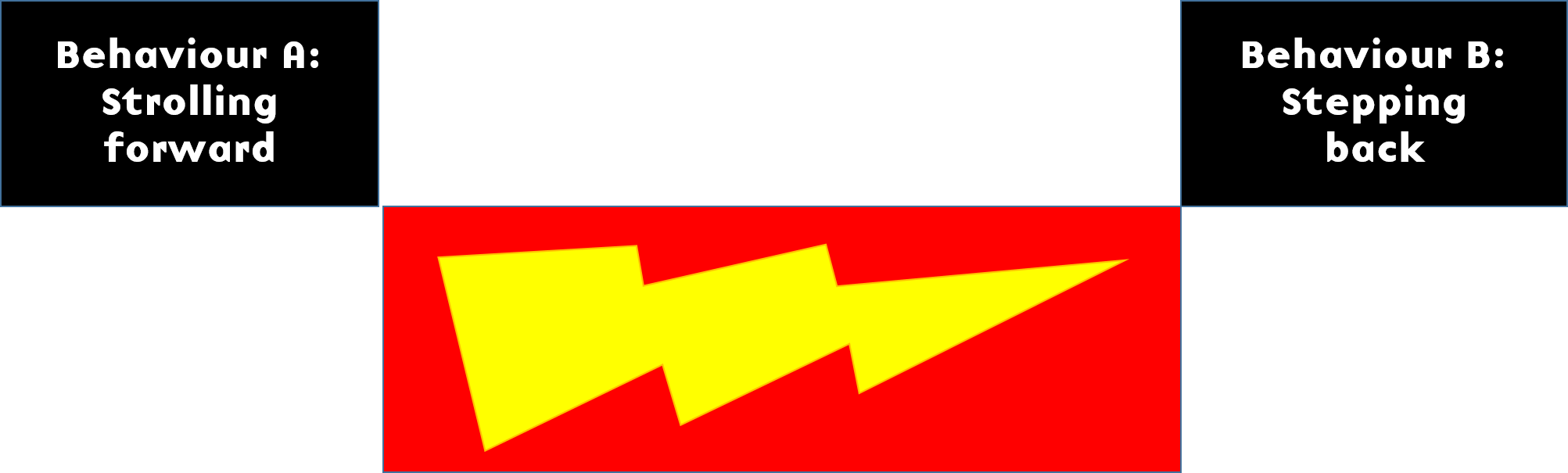

10. Punishment may lead to negative reinforcement.

Consider this:

Everything is fine. Lady is strolling into the kitchen.

Zapping starts. Lady startles, yelps and takes a few steps back.

Zapping stops.

Which of these two behaviours is Lady going to learn from?

Will she learn that strolling forward sets of the zapping? Or that stepping back stops it?

Are we punishing strolling forward? Or are we negatively reinforcing stepping back?

Are we providing a consequence? Or are we setting up the environment, making an antecedent arrangement?

Let’s say that it’s the latter. Lady may have learned that stepping back stops the aversive. Stepping back is negatively reinforced, and the intended consequence (C) has become an antecedent (A).

At first, she performed an escape response: she hadn’t learned the warning signals and got zapped until she happened to take a step back, which ended the zapping. After a while, she’ll likely learn to associate zapping with other stimuli in the context (such as whether she’s wearing the shock collar or not), and will start performing an avoidance response – and can thus avoid zapping altogether.

So, Lady may still go for the chicken on the counter in the absence of the warning signals or if the context is different enough from the original learning context (when not wearing the collar, for instance, or if the chicken is on the living room side table, or if it’s not a chicken but a steak) – after all, the main thing she’s learned is that when zapping starts, she should step back.

11. Punishment may cause avoidance behaviour.

Through negative reinforcement and classical conditioning, Lady might learn to avoid scenarios where zapping occurs.

She may learn to associate anything that was a part of the stimulus picture when zapping occurred to zapping – and start showing avoidance behaviour or becoming very immobile, even in a seemingly different context – as long as the new context shares some defining features with the punishment scenario.

The smell of chicken.

The rug in the bathroom, if it’s in any way similar to the rug in the kitchen.

The time of day.

A specific noise, say the dishwasher.

Wearing a collar.

The presence of the owner.

All of these stimuli might become conditioned punishers through that learned association.

The poisoned cue scenario is closely related to this: cues (or shall we say commands) taught with the threat of punishment tend to be avoided by the animal (4).

There’s an emotional component to this aversive conditioning also. If growling at a friend is punished, Lady will now like the friend even less.

Speaking of emotions…

12. Punishment could lead to fear.

Pain above a certain level leads to a fearful reaction. This is how fear conditioning is done in many animal experiments: by using for instance foot shocks (5).

And since punishment needs to be rather severe to work, fear is very likely a side effect of using these strong aversives.

This could have a few undesirable consequences:

- Fear could transform into defensive aggression, as discussed below.

- Fear could sensitize – so Lady becomes more fearful and responds to low-level-zapping.

- Fear could lead to aversive conditioning and avoidance, as described above.

Many people don’t recognize fear in animals – it looks different for different species but a common theme is moving slowly, freezing, or fleeing, accompanied by various body language signals associated with stress and discomfort.

Also, fear may affect learning in undesirable ways.

13. Punishment could reduce learning.

With raised intensities of zapping, at some point people’s and animals’ ability to think rationally about what is going on will diminish.

Do you know why most doors in public facilities such as theaters, libraries and schools open outwards?

Because in case of an emergency such as a fire, it’s too difficult to solve the problem of How to Open a Door by Pulling.

At a certain level of stress, many people can no longer remember that you can open a door by pulling it towards you. They can still push and claw at the handle, but taking a step back and pulling the door towards you becomes very difficult for many people when stressed enough. Also, there may be a panicked mob pressing at the door, so there’s simply no room opening it inward.

This phenomenon of reduced performance and learning when in high arousal is called the Yerkes-Dodson Law and is well documented in people and animals alike (6).

One concern with indiscriminately zapping dogs is that some individuals could have such a low threshold for when this effect sets in that they simply won’t understand what to do to stop being zapped, and maybe can’t even remove themselves from the situation.

14. Punishment could cause neurosis or PTSD.

One of the potential problems with the idea of using punishment when the owner isn’t even at home is the risk of equipment malfunction.

Zapping occurring in supposedly safe areas. Or no zapping happening in forbidden areas.

Along the same lines of reasoning, sometimes wearing the collar, sometimes not.

Any inconsistencies in punishment criteria is going to confuse the animal. To make matters worse, intermittent punishment can build very persistent unwanted behaviour if it’s maintained by a powerful enough reinforcer.

“OK…. So I’m safe in the kitchen when Mommy’s in there and there’s no chicken on the counter? But not if she’s not there… or wait, what if there’s no chicken? Hey – now they moved the rug, does that mean it’s safe?”

What happens when the learner has no control over when punishment is given? I mentioned learned helplessness above – another potential outcome is neurotic-like symptoms or PTSD (7).

15. Punishment could lead to aggression.

I can see three mechanisms by which punishment could lead to aggression:

- Punishment doesn’t have to be painful to have that effect – if it signals the unavailability of reinforcers it could be frustrating and lead to aggression (extinction / negative punishment)

- Fear very easily switches into aggression, especially if the animal is in any way cornered and there’s nowhere to run.

- The opportunity to attack is potentially a positive reinforcer. As the saying goes, the best defense is a good offence, and the animal may attack anything that moves – which makes sense since something nearby is likely to be the source of the aversive stimulus.

Even with an escape available, many animals still switch into aggressive mode when punished.

Lady may lash out at anything and anyone within reach, including children and other dogs.

If aggressive behaviour is punished, warning signals tend to disappear: for instance, if Lady was punished for growling, she may now bite instead.

I’m sure that some breeds are more prone to this type of reaction than others, but still.

One study, covering a large number of different breeds, showed that dogs that were routinely punished showed more problematic behaviour, including aggression, and were less well behaved than dogs trained with positive reinforcement (8).

16. Punishment depowers the learner.

Choice and control empower animals and promote welfare.

Choice and control is reduced in punishment scenarios, which suggests that punishment techniques are depowering and risk reducing welfare.

Effects of punishment on the punisher

17. The punisher thinks it’s working, when it’s not.

Back to being Lady. Say someone calls your name.

Hey, Lady!

You stop, turn around. What was that?

Ah, nothing. You go back to doing whatever it was you were doing.

You were interrupted, and now you go back to behaving.

This is often what happens when intended punishment occurs, regardless of the level of intensity.

Zapping interrupts ongoing behaviour. For at least a brief moment.

Then, depending on the intensity of punishment, two things may happen:

- Lady goes straight back to doing what she was doing, such as stealing a chicken.

- Lady abandons any chicken-stealing plans

The problem is that many people think that a short pause in the flow of behaviour means that the punishment is working.

It’s not.

Effective punishment stops both current and future behaviour. The behaviour shouldn’t happen again.

If the behaviour happens again, we’re not punishing.

We’re abusing.

But the damage is done – because the short break in behaviour has immediate effect on the brain of the person doing the punishing: that brain gets reinforced (as discussed below).

And that tends to stop the search for other solutions.

18. Fear could be mistaken for learning.

This warrants its own section. I already mentioned that fear is a common effect of punishment, and that learning could be negatively affected by fear.

The problem is that people may interpret any change in behaviour as learning.

Thinking that since Lady is no longer trying to get the chicken, she must have learned that she’s not supposed to steal food.

An alternative explanation may be that Lady has gotten zapped and is now in a fearful state. So rather than learn anything, she just changed emotional states and is now behaving differently.

To the uninitiated person, it looks like she’s learned something.

And in fact, there might be learning going on – just not the type we’re expecting.

We might expect that the animal learns “the bad thing happened because I stole the food” (operant learning), when a perhaps even more likely scenario is that the animal learns that “the bad thing happened in the presence of the five-year-old” (classical conditioning). So rather than no-longer-stealing-food (effective punishment of an operant behaviour) we’re now seeing growling-at-the-five-year-old (fear learning).

19. Doling out punishment is reinforcing.

Just like animals, people behave for effect.

People punish for a reason. Lady is doing something that’s annoying, and we’re trying to make her stop.

And she does. Even if only for a short while.

Sadly, that’s enough.

Something annoying stopped when the person delivered the punishment.

That’s a set-up for negative reinforcement, folks.

And it doesn’t matter that Lady starts doing the annoying thing again 20 seconds later, because the person’s brain is now infused with whatever neurotransmitters are involved with this type of learning. Dopamine, perhaps – it’s seen in some negative reinforcement learning.

All the side effects come later, too – but the instantaneous effect on the punisher’s brain has already predisposed that person to using punishment again. And the “effectiveness” of punishment is typically on a variable ratio schedule so it’s very resistant to extinction.

Punitive behavour is glorified in our society. It’s also easy, requires no training – and is copied by others.

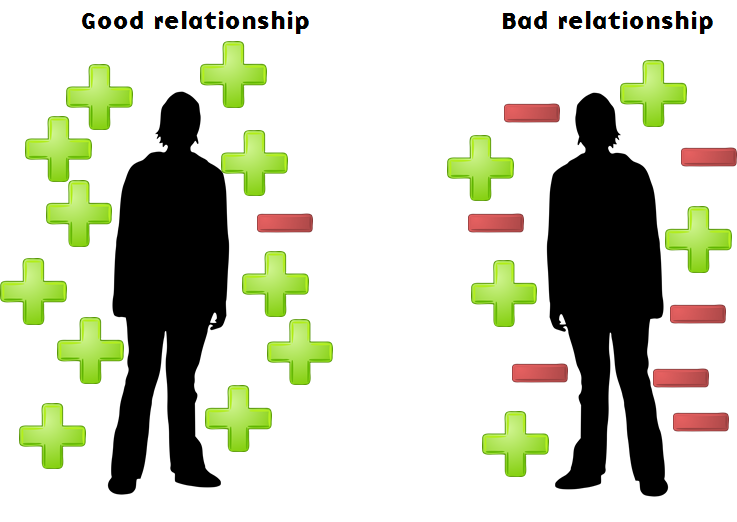

20. Punishment could damage the relationship.

Relationships are built through repeated interactions.

The interactions could be punishing – aversive to the animal.

Or they could be reinforcing – nice to the animal.

Over time, these interactions build the relationship – and the animal learns what to expect.

How often interesting things happen when the person is around.

How often nasty things happen when the person is around.

How predictably the human behaves.

How trustworthy she is, if you will.

Bad relationships don’t necessarily imply that the animal avoids the person. For instance, dogs form attachments to their owners, just like children do to their parents. So even with a bad relationship, dogs may seek out their owners.

The quality of the relationship will still influence their welfare, though.

And in the case of Lady stealing chickens at the kitchen counter: if the owner is around when zapping occurs, or if Lady perceives that the punishment is coming from her human, she’ll associate that person with being zapped.

And so, the relationship will be tainted. She may even avoid her owner or retaliate.

Or she’ll just steal when the owner is not around.

***

In addition to the references scattered throughout the text above, numerous studies have also attempted to compare specifically groups of dogs trained with electric collars with groups of dogs trained without. A comprehensive review of the effects of different training methods in the welfare and behaviour of dogs was done in 2017 (12), pointing out that the use of aversive-based methods is correlated with indicators of compromised welfare in dogs, as well as fear and aggression. The authors also pointed out some of the limitations of the early papers, and returned in 2020 with another publication showing that aversive-based methods do indeed compromise the welfare of dogs both within and outside of the training context (13).

***

So, what to do?

It’s easy to gleefully list all the potential downsides of punishment, but how do you actually solve the stealing problem?

Actually, there are several ways of addressing the problem of counter surfing.

Setting up for failure – or success?

Let’s start with: what are Lady’s options?

Currently, the kitchen counter is fun, and the floor is boring.

This set-up is likely what motivates Lady to explore off-limits.

One hugely effective way of shifting that balance is to make the kitchen counter boring, and the floor fun. Ideally before the counter-surfing behaviour has become habitual.

Very likely, Lady will shift her behaviour too – you’re setting her up to be successful.

She’ll have no reason to go to the forbidden areas, because they would be boring.

Shifting the balance of reinforcement requires two (2!) things:

- Thing 1: Remove or reduce the source of reinforcement in the forbidden areas. Don’t leave the chicken on the counter. In fact: don’t leave even a crumb of anything remotely resembling anything edible or interesting. Forbidden areas should be boring.

- Thing 2: Make the allowed areas fun. While Lady probably wouldn’t mind, it’s probably not advisable to put three chickens on the floor. Rather, toys, puzzles, food mazes and whatnot – whatever she likes to engage in and that will keep her occupied.

Teaching impulse control

Also, you may want to do some impulse control training with Lady, so that she learns that by refraining from taking something she wants, something fabulous will happen.

Here are some key pointers on how many people teach a so-called leave-it cue:

- Present inaccessible food (hidden in the hand) – as soon as Lady looks away or turns away from it, she gets a treat.

- Gradually shift the criterion so that Lady gives eye contact rather than focusing on the food in your hand. An intermediate step is to first uncover the food when she looks away, then reward her for staying away from the uncovered food (which is more difficult than staying away from covered food).

- Don’t use any signal to tell Lady when she’s doing the wrong thing such as mugging (many other trainers will say “wrong” or “eh-eh” or the like) – let her work out for herself that mugging gets her nowhere and eye contact gets her something fabulous.

- Don’t pull your hand away when she tries to mug your hand – that could make it into a game, setting of her hunter’s instincts.

- Change the set-up several times (direction, location, food type etc) so that she can learn to generalize.

- Generalize the concept further by putting on a leash and throwing food out of reach on the floor – use a harness rather than collar (reduces strain on Lady’s neck if she lunges for the food). When she looks away from the food – give a treat.

- Gradually shift the criterion so that Lady looks at you rather than the food on the floor.

- Once she is reasonably reliably avoiding mugging, introduce the leave-it cue.

- Work on duration.

- Gradually make it even more difficult – responding to the cue even when you’re not in the room.

Emily Larham (aka kikopup) beautifully illustrates this training sequence in the video below, and explains it in more detail.

Nowadays, modern trainers tend to use an errorless approach when teaching leave-it. Check out Sarah Stremmings’ blog post right here.

The New Standard of Animal Training

To me, a punishment-based remote system is not a New Standard of Animal Training. That approach has too many potentially severe side-effects – it would never be my first choice of addressing problem behaviour.

Rather, when dealing with counter surfing, I would arrange the environment so that the unwanted behaviour is unlikely to occur, and so that Lady has plenty of other, acceptable, options.

I would set her up for success – rather than failure.

I would teach Lady that it’s worthwhile to ignore temptation – reward her for doing something else, such as orienting towards me and giving eye contact, or a relaxed lie-down in a specific location such as on a conveniently placed mat.

Building relationships based on trust and a history of positive reinforcement rather than punishment will result in a more confident, happy Lady.

Yeah – I know, you’re burning to ask this question.

But what if the non-punitive approaches don’t work? Or the scenario is vastly different?

What about life-or-death situations?

Shouldn’t you never, ever use punishment?

When to use punishment

Despite the list of downsides, there might be a place for punishment once in a blue moon – at least in theory.

If Lady was about to get run over by a car, I would do anything to prevent that from happening. That goes without saying. There are dangerous situations where you immediately need to stop behaviour, to save lives or avoid danger.

Also, getting an adrenaline rush is normal in such a situation, which may lead to a harsh tone of voice and forceful behaviour. This might be punishing to the animal, regardless of our intentions.

Still, if that happened, I would consider two things afterwards:

- How badly did I just mess up? Which side effects can I expect to see? Can I reduce the impact of those side effects?

- I wasn’t prepared for this – what can I do to avoid this scenario in the future?

I think many animal owners run into these acute situations at some point, where you need to act quickly and resolutely in a way that’s aversive to the animal, and therefore constitutes a potential punisher.

Animals recover well from the occasional punisher, that wouldn’t worry me too much. After all, that’s life. We stub our toe. Miss the bus. Get rained on.

“The occasional defensive punishment is likely to be treated less as a shock than as a signal that a reasonable boundary has been overstepped” – Murray Sidman (9)

I can relate to that.

But that’s another story. That’s the emergency situation.

To be clear, remote training with shock collars are not emergency situations.

Even if I had a dog, or shock collars were allowed here in Sweden, I would be extremely hesitant to use them. For one, I’d be afraid that I wouldn’t do it right. I’d try solving my training problems in other ways; after all, positive reinforcement is forgiving.

Punishment is not – one mistake might take forever to recover.

Here’s the paradox, as I see it: using punishment effectively to change behaviour in our companion animals without triggering any of the side effects takes tremendous skill and a thorough understanding of learning and behaviour.

And once people become that tremendously skilled, the need to use punishment to resolve any unwanted behaviour all but evaporates: many such trainers have so many other tools in their tool box that they no longer feel the need to reach for the one that involves positive punishment.

But sometimes, in theory, we might imagine running into a problem behaviour that, despite doing – and revisiting – the detective work involved in understanding the function of the unwanted behaviour, despite skillful attempts at resolution and using a battery of well-proven humane techniques, and despite discussing the situation with other experts in the field, we might perhaps imagine that hypothetically, some situations simply can’t be solved through any other means than using punishment.

In such cases, punishment may be a solution while also trying to mitigate the potential side effects – an empowered animal should recover quickly if this is indeed a rare occurrence.

For me and many others, punishment would be a last (often hypothetical) resort, to be considered when nothing else works – it’s not the first thing to try, or even the fifth.

Actually, following the concept of the Humane Hierarchy (10), and the LIMA (Least Intrusive, Minimally Aversive) approach, punishment would fall about the eight or so, depending on whether we’re discussing negative punishment (removing something desired) or positive punishment (adding something aversive).

And indeed, if we step outside of the Humane Hierarchy and look at how mood states and emotional reactions to ongoing events influence perception, decision making and behaviour, very often simple mood state adjustments or counterconditioning might help change the animal’s overall behaviour, pushing the need for punishment even further down our list of potential useful interventions and tools.

It’s beyond the scope of this blog post to go into details of how to do this, but I do cover it in great detail in my Resolving Challenging Behaviour online course.

When choosing a training approach, remember: Positive reinforcement works, and punishment is potentially dangerous.

It’s not to be undertaken lightly.

I guess that’s one reason that I was indeed speechless when first seeing the remote punishment video: it really set the animal up to fail and didn’t in any way, shape or form mitigate the potential adverse effects of punishment.

***

Edit:

One of my readers reached out and suggested that I stop fearmongering and instead learn from a well-respected balanced trainer how to carry out shock collar corrections safely.

And to be honest, I might well be fearmongering, to a certain extent – I’m not a dog trainer and haven’t seen first-hand any of the side effects described in this blog post. Certainly, with regards to well-educated balanced trainers, it’s possible that they have learned (perhaps the hard way) to balance the risks and reduce the likelihood of most, if not all, the potential fallout detailed here.

But this blog post isn’t written with the skilled balanced trainers in mind. I don’t think it will change their minds, anyhoo.

Rather, it’s written for the unsuspecting dog owner, the one who grabs one of these collars off a shelf, reads the instructions on the packaging, straps it on the dog and start zapping away – and then wonders why their anxious dog started growling at the five-year-old.

Again, I could be wrong about parts or all of the above – perhaps all that research that has come out in later years is seriously flawed in some way or another.

However, one interesting thought experiment is to ask oneself: if there are two ways of being wrong, which mistake would you rather make?

- Would you rather assume that punishment is problematic, when in fact it isn’t? Or,

- Would you rather assume that punishment is not problematic, when in fact it is?

Let’s say I’m making mistake number 1 by publishing this blog post – let’s, for argument’s sake, say that I’m vastly inflating a negligible issue. What’s the worst that could happen?

- In scenario 1, the worst that could happen would perhaps be that the reader would avoid using punishment-based techniques, perhaps buy a clicker rather than an electric collar, and get interested in some of the alternative techniques just barely outlined here. And the dog would keep stealing the chicken on the counter (assuming none of the alternative methods to deal with that particular unwanted behaviour suggested here actually work).

If that’s the worst that could happen, I think the outcome is actually pretty good!

And to continue this thought experiment, let’s say that instead it’s my reader who is making mistake number 2, neglecting the real problems with punishment. What’s the worst that could happen?

- In scenario 2, the worst that could happen would perhaps be that the punished animal responded with fear and aggression, learned to associate the zapping with the family’s five-year-old child and attacked – and had to be euthanized as a result.

In other words, the outcomes of being wrong in scenario 1 versus scenario 2 is nothing short of mind-blowing in order of magnitude. In my mind the issue isn’t so much who is right, rather it’s what is the potential cost (worst-case scenario) of being wrong.

***

Interested in checking out my upcoming courses? Sign up be informed when I update this blog, give free online webinars or when my online courses about animal training, behaviour and welfare are available! Admission is typically only open for a short while, so don’t miss the opportunity!

Reading list and references:

1 – Seligman 1968: Chronic Fear Produced by Unpredictable Electric Shock.

2 – Miller 1960. Learning resistance to pain and fear: Effects of overlearning, exposure, and rewarded exposure in context.

3 – Maier & Seligman 2017. Learned Helplessness at Fifty: insights from Neuroscience.

4 – Murrey 2007. The Effects of Combining Positive and Negative Reinforcement during Training.

5 – Rescorla 1968. Probability of shock in the presence and absence of cs in fear conditioning

6. Nickerson 2021. The Yerkes-Dodson Law and performance.

7. Van der Kolk et al., 1985. Inescapable shock, neurotransmitters, and addiction to trauma: Toward a psychobiology of post traumatic stress

8. Hiby et al., 2004. Dog training methods: Their use, effectiveness and interaction with behaviour and welfare.

9. Sidman, 1989. Coercion and its fallout.

10. Friedman, 2008. What’s wrong with this picture: effectiveness is not enough.

11. Schilder & van der Borg, 2004. Training dogs with help of the shock collar: short and long term behavioural effects.

12. Fernandez et al., 2017. Do aversive-based training methods actually compromise dog welfare?: A literature review

13. VIeira de Castro et al., 2020. Does training method matter? Evidence for the negative impact of aversive-based methods on companion dog welfare

14 replies on “20 problems with punishment in animal training”

[…] is one of the main problems with punishment as a learning […]

shock collars for dogs are banned in the netherlands From January 1, 2022 to.

Nice read i have some things to do 😉

That’s great to hear! 🙂

This is a very interesting read. My husband and I have trained dogs for scent detection and have used a positive reinforcement way for this. Your article helped to put some of our “unknown” details into perspective.

Great to hear that! 🙂

Absolutely, the more the merrier! 🙂

Very helpful post. I trained my older beagle with mild negative reinforcement (tug on collar with release for wanted behavior), my younger beagle with clicker. The attitude difference is considerable. Clicker can appear to take longer in the beginning, until you get the hand of timing and setting the situation for success. I could never go back to negative reinforcement.

PS – the reference link to Friedman (2008) does not work

ah – thanks for alerting me! I changed it. 🙂

[…] check out the leave-it game. It’s under the subtopic “teaching impulse control”, about half way through the […]

[…] is one of the many reasons that you don’t want to use punishment in your training: using aversives could lead to avoidance, aggression and a disrupted human-animal […]

[…] them whether they use corrections as part of their techniques (if they say “yes” without hesitation, move […]

[…] je deze vragen stelt dan wanneer je een straf uitdeelt. Nog niet overtuigd? Lees dan een keer “20 problemen met straffen” van Karolina Westlund. Leuke leestip, en niet alleen voor mensen die dieren trainen, maar ook voor de mensen die zich […]

[…] Punishment often has side effects such as aggression or fear, and potentially damaging the relationship between owner and pet. […]

[…] I’ll just drop this topic for today. Though I did write about the 20 problems with punishment here. […]