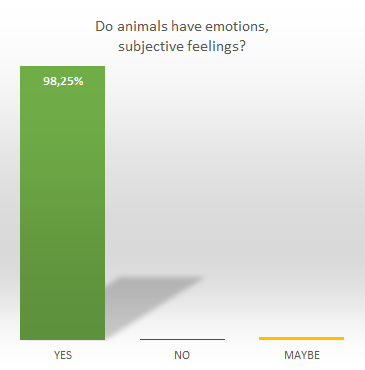

Do animals have emotions: can they experience the same subjective feelings of fear, rage and joy that humans can?

A seemingly straightforward question, and one that I recently asked on Facebook.

Here’s what you answered, Facebookers:

The overwhelming majority exclaimed “YES!”, with a few undecided and even fewer saying no.

3, to be exact.

Interestingly, if this question had been asked, say, 20 years ago, I think the answer may have been very different.

Facebook wasn’t around then, though.

But when Jaak Panksepp (one of the pioneer researchers studying emotions), reported that rats laugh when you tickle them, back in the late 1990s, he was questioned and ridiculed by the scientific community.

“Moahahahaha! That’s preposterous!” they said.

Not so anymore.

Now there are congresses on the topic of Affective Neuroscience, the zone where neurons, emotions and cognition meet. The scientific community is mostly aboard – though some of Panksepp’s conclusions are still debated.

In the Facebook crowds I polled, whether-animals-have-emotions was not a particularly controversial topic, and many even suggested that the issue is resolved once and for all.

However, I’m not sure how representative the responses I got were, considering that I hang out in animal training groups.

What the average pet owner, or people without pets, or people from other cultures, would answer – I don’t know. But I suspect that I’d get more mixed answers from another crowd.

So, I sent Jaak Panksepp an email, asking him. He graciously answered within a few hours, saying that controversy is diminishing except in “people who have much to lose”, such as in the field of human cognitive neurosciences.

What is the issue, then?

Imagine a zebra spotting a charging lion, and dashing away.

Animals run from danger. So do people, and we call the emotion associated with scampering off to safety ‘fear’.

The controversy is not whether animals show responses analogous to ours when exposed to danger (they do), or have physiological reactions similar to humans (they do).

The question is, do zebras have the same inner experience, the subjective feeling of the emotion, which goes with running-for-your-life-from-a-pursuing-lion?

Or are they simply going through the motions, like machines? The high blood pressure, the cortisol release and the glucose increase serving the beast to run faster, without the accompanying feeling of terror and dread?

Some argue that animals have these subjective feelings, others that they don’t, and yet others, that there is no way we can test it to find out.

Not that you’d guess that this was a big issue from looking at my small data set… and I won’t go into the details of their arguments in this post.

Does it matter whether animals have emotions?

I think it does.

I think it matters whether we regard the fleeing zebra as fearful, as opposed to “running-when-exposed-to-lions”.

I think that distinction will help us take better care of them, we’ll all be a bit happier – and the world will be a better place.

Full disclosure: I happen to subscribe to the “of course animals can feel the emotion”-crowd. To me, it makes perfect sense that they should, considering that we share the same evolutionary past.

Emotions are closely linked to behaviours with tremendously important survival value, and such mechanisms tend to be stable over evolutionary time.

I have feelings, I’m assuming my relatives do too.

Including at least my fellow humans, mammals and birds.

That’s how I rationalize my conviction. Also, I happen just think that they do, for no reason other than that I get that impression after hanging out with animals.

The “because.I-think-so” is not scientific, though, and the skeptics would tear that argument apart in no time.

I’m not all that interested in having that discussion though.

I don’t care particularly if I’m right – I often change my mind when I learn new things.

I’m more interested in another question:

What would be the cost of being wrong?

People may be wrong in two ways. In science, we call it the type I and type II error, and I tend to forget which is which. But one error is referred to as the false positive, the other as the false negative.

Let’s play a little hypothetical game.

The what-happens-if-you’re-wrong-game.

Animals either have subjective feelings, or they don’t. And some people believe that they do, and some don’t believe it. Ergo: some people have it all backwards.

Admittedly, I could be among those in the wrong.

Annoying as that would be, it’s a possibility.

In this game, I’m assuming that we would treat animals differently depending on if we think they have emotions, especially when it comes to suffering.

With regards to emotions in animals, what would the two hypothetical misconceptions look like?

- If animals in fact don’t have feelings and thus couldn’t suffer emotionally, the misconception would be to assume that they have feelings. A false positive. If I were mistaken, this would be my error.

- And vice versa, if they do have feelings, then stating that they don’t is a false negative.

To me, the key question is not whether animals experience the feeling of emotions, but which mistake would you rather make?

This is hypothetical, of course. But a sobering thought: what if you’re wrong?

Personally, I can live with being mistaken about animal emotions.

If it turned out that they don’t have emotions, I can shrug off my misguided notion with a slightly bruised ego.

I would have wasted time, commitment and money trying to make life better for animals and minimize their suffering.

Pearls before pigs, in a manner of speaking.

For me, it would be more difficult to dismiss my past misconception if it included neglecting suffering. If I had treated animals as if they had no capacity to be frightened or happy, and later found out I was wrong, I’d be very distressed.

I would thus encourage skeptics to give animals the benefit of a doubt, if for no other reason, to reduce the pain of potentially being mistaken.

Act so that animals in your care don’t suffer, regardless of whether you think they could.

While you’re at it, try to make them happy, too. The absence of suffering does not equal high well-being, after all.

But being able to live with yourself in case you’re wrong is not the only reason to be nice to animals. It certainly isn’t the most important reason.

Connecting emotionally to animals feels good.

People have an emotional need to connect with animals. We cuddle, play and confide in our animal friends. A huge chunk (if not all?) of the human-animal bond is emotional, and we tend to get more attached to mammals and birds than to fish.

I would guess that the significance of an animal in the lives of the people caring for her depends at least in part on how well she attunes to her owner’s emotional needs. And it’s my conviction that part of that attunement is because mammals and birds behave as if they have emotions, too.

Indeed, the human-animal attachment involves the feel-good hormone oxytocin, among others, which has been shown to increase in both humans and dogs during positive interactions.

So, not only do dogs behave as if they have emotions, their hormonal system mirror ours, too.

Health benefits of pet ownership includes reduced worry, depression and pain.

How much of this effect is due to the emotional involvement?

A great deal, it seems.

Does someone who thinks animals have emotions have better relationships with their pet than someone who doesn’t?

Are they more helped by a therapy dog visiting the hospital?

That hasn’t been specifically studied, as far as I can tell – but it’s not implausible since bonding involves emotional connection.

But feeling-good-by-bonding-with-your pet isn’t the most important reason for being nice to animals.

How assuming that “animals have emotions” benefits kids – and society.

It’s been known for some time that it is beneficial for kids to have pets at home. However, studies have shown that it’s not the being-close-to-pets that’s relevant, it’s the forming-a-relationship-with-animals that makes children more socially competent and empathic.

We know that improving kids’ kindness and caring towards animals have beneficial effects on children’s prosocial skills.

How does this relate to whether animals have emotions?

Again, relationships involve emotional connections.

Now I’m going to be speculative: I think the quality of the human-animal bond improves if one assumes that animals have subjective feelings, too.

I think it’s more difficult and unlikely to become truly attached to a Tamagotchi or a toy animal than a real puppy.

In other words, I’m arguing that assuming that animals have emotions could improve the human-animal bond, produce more socially competent youngsters, who then grow up to save the world from war, famine and climate change.

Sort of kidding, but I’m on the verge of singing a teary-eyed “we shall overcome” too.

The most important reason to be nice to animals and behave as if they have emotions is that kids mimic adults.

If you behave nicely towards animals, your kids will too. In doing so, they become more socially competent, and empathic – toward people.

In short, assuming that animals have emotions makes the world a better place, for people as well as animals.

A note of caution. “Being nice to animals” is complicated.

Over-feeding pets is a big problem, as many vets will attest. And although anthropomorphizing is sometimes a great shortcut to understanding and caring for animals, it carries some major caveats too. A topic for another day, perhaps. Actually, I wrote a bit about that in this post. If you’re an aspiring animal trainer, you should read it.

***

Want to learn more? My online courses are wildly popular but only open for admission occasionally. Sign up to be kept in the loop, and I’ll keep you posted on upcoming free webinars, masterclasses, silly experiments and new blog posts, too!

References:

Ascione & Weber (1996). Children’s attitudes about the humane treatment of animals and empathy: One-year follow up of a school-based intervention.

Odendaal & Meintjes (2003). Neurophysiological correlates of affiliative behaviour between humans and dogs.

Poresky & Hendrix (1990). Differential effects of pet presence and pet-bonding on young children.

12 replies on “Why you should behave as if animals have feelings even if you don’t believe that they do.”

just look into their eyes, feel the affection they show when they approach you and how they ask for safety and love. No doubt in my mind…

No doubt in my mind either… but I don’t think everyone agrees with us..!

“is there a core emotion that could be involved in producing this behaviour?”

I have been asking this question with my introverted horse for a long time and often can’t figure it out. It is often very subtle. I think I need to make a chart.

Maybe you already have? A figure with the core effect space overlaid with operant quadrants , core emotions, and the neurotransmitters associated with each core emotion? If so can you tell me where it is? That might help me sort out what he is feeling.

… nope, no such figure at present! 🙂

[…] weaned too early, and whether hyperflexion in horses should be considered abuse. I’ve argued that we should assume that animals have emotions, if only because that makes the world a better […]

Gregory Berns is a Neuroscientist and in 2012 he trained his little dog to lay still in an MRI this was the first time a dogs brain was studied while the dog was alive since then numerous dogs have been trained to accept an MRI. One of the studies showed that while a dog was under the MRI and the dog’s owner entered the room the part of the brain that controls the love emotion so to speak, lit up like a Christmas Tree. This proves to me what I knew all along that dog’s do have emotions and are capable of feeling love.

nice! 🙂 Thanks for sharing!

Hello Karolina

I love this. I am lucky to have just found your seminar still available and watched this morning – now sent the link to all my animal loving friends! As an animal communicator sharing my home with many animals, I’m always being asked and challenged on the emotions issue. Out with my four dogs after watching, one ran full speed into a telegraph pole, too busy watching his playmate. His fear response (and pain!) was tangible, as was the comfort he gained from me and the other chaps fussing over him. Then he was invited to play once more and soon forgot his discomfort. So many emotions at play! I will keep watching for more from you, keep up the good work, and thank you!

🙂 Thank you so much for reaching out, so happy to hear from you! What a lovely scene you describe, recovery after minor trauma… have a great week! //Karolina

[…] most modern animal trainers don’t question that animals have emotions. It’s just that when it comes to dealing with animals, many tend to address the observable […]

Good article. As an aside, I answered your survey, and I believe I answered, “no.” Not because I don’t believe animals have emotions, or even some which are similar to ours. It was the way you worded it. As I recall, you had also used the term, “rage,” in the question. As a behavior modification trainer, who often goes to work with dogs, horses, cats which are acting aggressively, I run into so many owners who blame the behaviors on jealousy, anger, rage, etc. I find that often they are wrong in their “interpretation.” While the fact that they believe animals have these emotions is not bad, I try to explain to them that assuming the animal feels the same way they would in the situation is not fair to the animal and can lead to problems. It is not that the animal does not feel emotions, just don’t assume it’s your emotion in a specific circumstance. (just because this situation would make you feel jealous, don’t assume that IS what the animal is feeling). The rage word is what really made me go with my no answer. I really feel animal rage is different from what most people would describe to be rage in humans (which is mostly attached to feelings of extreme anger). So, maybe I was being too picky about how it was worded, but If that word had been omitted, I would have answered yes.

Hey Denise,

Thanks for taking the time to comment! I realize that people had different motivations to select “no” or “maybe” to that question – and you certainly raise a valid point. Do animals experience the emotions in the same way as we do…? I think we may never get to the bottom of that question. We do know whether they appreciate the emotions or not. Then again, I’m not sure that two people experience an emotion the same way…! 🙂