It took me years to realize this, but there are some approaches that really propelled my learning about animal behaviour management in general, and animal training specifically.

Here are the four tactics or concepts that I’ve found most useful:

Learn from many teachers

I still remember the goose bumps I got when I first came across a professional animal trainer and got to see her in action. I saw a monkey change his behavior over the course of a short training session, and I was hooked. As an ethologist interested in animal welfare, the implications were enormous – and it looked like great fun, too!

I started reading. Attending courses and training conferences, watching DVDs and discussing with like-minded people. Training animals myself. One of the greatest insights I have from these early exploratory days is this: as I learn from different people, their perspectives, theories and experience come together synergistically.

They each give me their pieces of the puzzle, and then my brain fills in some of the blanks between neighboring pieces. I still don’t have all the pieces, and some of them are likely wrong, but still.

I sometimes meet people who have met influential, charismatic animal trainers, and looked no further. They follow them faithfully, put them on the proverbial pedestal and take pride in putting all others aside. These devout followers read their books, attend their seminars, and defend them vehemently if their training approach is criticized.

While this dedication is admirable in a way, it’s also disadvantageous in that even the most determined trainee won’t learn everything that their teacher knows. Also, they have no way of identifying weak points in the guru’s approach to interacting with animals, nor get the epiphany of connecting dots between different perspectives.

By having multiple teachers, many of those weak points become blindingly obvious.

Not all, because we tend to be steeped in the same views on animals, living in the same 21st century paradigm – sharing the same cultural fog (a favourite topic of behaviour analyst Susan Friedman), as it were. At the very least, by having many teachers and sources of inspiration, you start seeing where different trainers agree – and where they disagree.

Learn from many individual animals

The animals you train are your teachers, teaching you the skills needed to be a successful animal trainer. As humans, we’re creatures of habit, we’re superstitious (seeing patterns, assigning meaning and correlation where there is none) and we generalize what we learn.

I hate to shatter your illusions, but having excelled at training one individual animal does not automatically make you a good animal trainer.

I recently spent 3 months cat-sitting. Before our new guest arrived, I was confident that it was going to be a breeze: after all, I grew up with a cat who was with me for 20 years. I understood her every meow, I knew her favourite scratching places and her dislikes. On top of all that cat experience, I’d earned a phD in ethology, taught university level learning theory and behaviour management.

Cat-sitting wouldn’t faze me.

Or so I thought.

Needless to say, it was a sobering experience. Much to my surprise, getting to know a new cat took some hard work, mostly because many of my expectations of living-with-a-cat weren’t met.

This cat doesn’t like to be touched, but my childhood friend loved being petted.

This cat doesn’t flinch when my kids holler and run about; my old kitty would have run off to hide.

This cat talks to me, and I don’t quite know what she’s saying.

Animal training is all about flexibility. It’s changing your own behaviour so that the animal will do the same.

If you’re only training one individual animal, you’re not stretching your wings enough and it’s my warmest recommendation that you look around for some other trainee.

Which, incidentally, brings us to the next topic.

Learn from several animal species

Did you ever train a cat? Many cats will lose interest in a training session very quickly: the first clicker training session that I attempted with my feline guest was less than a minute and, if I’m not mistaken, involved 6 or 7 repetitions.

Then she walked off, tail high.

In contrast, training undomesticated animals such as primates, the first training sessions often involve gaining trust. Addressing safety issues, avoiding eye contact, moving slowly, finding the best treats to encourage cooperation. Forget the clicker, get them to take food from you.

Cooperation was not a problem the first time I trained a dog. Nevertheless, I managed to mess it up completely. The small Papillon gave eager eye contact, started offering her whole repertoire of tricks, anticipating my next cue. My timing was off, my plan went out the window, she barked and danced and my fellow trainers who witnessed the sorry affair probably snickered inwardly.

Some things that influence the outcome of a training session will be the animal’s temperament and personality, the quality of the relationship, the presence of distractions and potentially aversive stimuli.

If you don’t have time to work through a whole menagerie, which species is the best to learn the skills of the trade from?

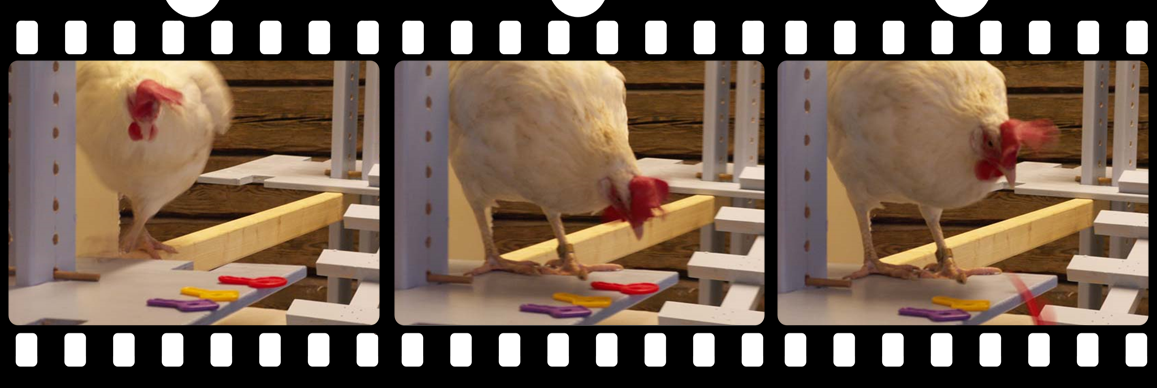

Well, Bob Bailey, one of the animal training gurus I’ve had the privilege to learn from, having trained tens of thousands of individual animals and several hundred species, suggests chickens. They’re motivated, active, not all that distractible, and their behaviour is generally not influenced by social cues from you.

Although my practical experience is but a fraction of his, I agree.

Keep an open mind

Each animal trainer has her own journey, but typically something triggers the urge to learn more about how to train animals.

Someone may see a dog agility show, get instantly fascinated and want to learn more.

Another may learn that there are other ways of weighing a bear in a zoo than darting it with a sedative.

A third may search desperately for ways of resolving the screaming habit of the new parrot.

Here’s my journey.

As an adolescent cat owner, I thought Relationships were all that mattered in achieving high animal welfare, apart from the veterinary perspective.

Later, I assumed that I knew all there was to know about animal behaviour as a trained Ethologist, looking at behaviour from an evolutionary view: how to set up the environment to promote natural behaviour.

Then I learned about Clicker Training, and practical applications of Operant Conditioning. It blew me away.

Then I realized that clicking and treating wouldn’t always be the best approach when training; Respondent Conditioning is hugely important, too. I now consider Counterconditioning one of the five most important tools in the animal trainer’s tool box.

Not to mention Habituation and its pitfalls – and the power of Systematic Desensitization.

What not to do is equally important as what to do, as an animal trainer.

Then I started really considering the Ethics of Animal Training: if there are several ways of getting behaviour, which should you choose? How will this choice impact current and future behaviour, the quality of the relationship, and the animal’s wellbeing?

I learned Behaviour Analysis: a scientific discipline specialized in really dissecting, understanding, and changing problem behaviour.

Then I tapped into a controversial subject, Affective Neuroscience: emotions and their impact on behavior. This topic really helped me predict, understand and prioritize: which behaviours are important?

Never one to shy away from controversy: my recent discovery is Animal Communication, a field that I can’t quite wrap my scientific brain around and that sets off all my Sceptic’s warning bells. It turns out that there is seemingly robust scientific evidence, including double-blind, randomized studies, that humans can communicate telepathically, including with animals – and learn what ails them.

I realize that for some of my readers, this will be a no-brainer, and for others, the same alarms will go off.

Quantum physics seem to be able to explain these findings, and I’m ambivalent and intrigued.

I encourage an open mind when exploring these topics: you might learn something useful to you – and the animals in your care.

I’m always learning – how about you?

***

In my blog posts, free webinars, masterclasses, silly experiments and online courses, I return to most of the topics mentioned above. Admission is typically open for a short time, so sign up below to get notified so you don’t miss the opportunity of joining!

Erickson (2011). Intuition, telepathy, and interspecies communication: a multidisciplinary perspective.

18 replies on “How to become a better animal trainer.”

While I lack animal communication skills, I have worked for 8 years with an animal communicator, always accurate, who works with my deceased geriatric Dutch Shepherd to provide insights into a dog which might interest me. In the latest episode as I considered a border collie needing a new home, I learned that animal wanted to run over several acres which I don’t have. Therefore, the animal wasn’t interested in me. The breeder who had the dog was skeptical of this attitude but I’m pleased to report that the dog has found a home with the acreage she needed.

A project entitled http://www.givinganimalsvoice.org is starting with the intent of using bona fide animal communicators to help animals in

shelter situations.

I realize that human – animal commutations sounds bizarre, but after eight years with communications between my late dog, the animal communicator and me, I know “it” works as long as I remember that animals live in the present. What may seem unusual, if considered as a description of a present circumstance, makes perfect sense.

Thanks for sharing your story! 🙂

Your comments are very interesting. I have mostly trained horses with the pressure and release method. But I too, have just discovered animal communication and am slowly trying to get my head around it to adopt a ‘nicer’ way of training horses, I want the relationships without feeling like I’m forcing them to learn. Totally enjoying this course for the information that is available to build upon.

Really interesting your comments about animal communication. For a while I’ve been extremely sceptical but recently I thought ‘what the heck’ and did a short class on it. Well, mindblown! Im very much into the science but I also like to try things because, how can I slate something that I have absolutely no understanding or experience with. Its definitely opened up a whole new door.

It’s easy to dismiss that which we know nothing about. And to bunch it all into one big “mumbo jumbo” pile… well, time to start sifting through that pile and find the interesting nuggets..! 🙂 Science will eventually catch up.

Going out on a limb here……….

I have never accepted nor agreed that “Interact with an animal, and you’re training it. Whether you intend to or not.”

Yes, I believe everything in the animals sensory perception influences the animal in one way or another and the animal learns from the influences and/or observation and to some degree or other, the animal learns from those influences and observations. But not all learning is the result of training.

I do not agree that all the birds, snakes, chickens and so on can be considered to be training the animal considering the common use and definition of the word training just because the animal is learning something due to their presence.

And to me, the concept gets in the way of some things. “I’m going out to spend some one-on-one equilateral with my horse…..ulp!…….better be careful……they say I’ll be training him.”

The extension would be that we are training our parents, teachers, children, cousins, or anyone we interact with, and they us.

I just don’t think that is meaningful or true even with the wide acceptance and belief of the concept within the animal and horse world.

I would say: It is important to be mindful of your emotions and activity any time you are within the sensory environment of the horse (or other animal) whether you are actively training or not because just like humans, the horse (or other animal) will be watching facial expressions and body language while forming conclusions about who and what you are.

Hi Harold – and thanks for sharing your thoughts on this!

I agree – not all learning is the result of “training”. But that’s not what I’m saying. I’m saying that the animal learns from the interactions they have with you, and change their emotional state and / or their behaviour in response to it. That’s what I’m defining “training” as here – the animal changing their behaviour because of your presence and behaviour. What I’m getting at is that so many people are completely oblivious to this.

Do I mean that learning occurs every single moment of every interaction? No. But if you have some type of interaction, the animal will likely sort you into one of three buckets: scary, boring, or fabulous (or somewhere in between) – and yes, that extends to our parents, teachers, cousins etc as well – one might conceptualize a relationship as reinforcement (or punishment) history…! 🙂

I agree with everything you have said except the definition and use of the word ‘training’.

Yes I know it’s a veritable mantra across the horse world but I do not believe the mantra gets across what it is intended to get across. I think the mantra too often creates tension within the well meaning equine owner which the horse clearly reads which in turn reduces the depth of interaction.

I am all about people being aware of the emotional intelligence of the horse and the depth of their responses to our body language and so on. I just don’t think the mantra conveys the importance of our presence in ways that does not negatively impact mind and behavior of the owner/beginning trainer.

To me, the mantra just seems to compromise what I believe is most important which is focusing on our internal attitude towards the animal and our emotional congruence during our interactions.

This is the first time I’ve felt safe enough to express these thoughts. Thank you for the safety!

You have my attention – but then you always do! Behavior science has developed so much from my college days in psychology in the ‘70’s. Integration of knowledge from other fields is fascinating! And seems to provide evidence for things I already thought were true like animals have feelings/emotions; relationship matters!

🙂 Oh yes there’s SO MUCH going on in behaviour science – and its applications! Cognition, emotion, communication… we live in interesting times!

I have a very logical mind, and I also a few friends and customers who are animal communicators. Some of the things they have told me are hard to dispute – very specific injuries, fear and dislike of a farrier that I totally agreed with, and stories of the wild dogs that go by my injured horses pen every night. Game cam showed a pack of coyotes doing just that. I wouldn’t be doing clicker training if I hadn’t had a conversation with an animal communicator 14 years ago.

Thanks for sharing! It will be interesting to see what happens in this field in the next decade! 🙂

[…] course, acquiring good habits is not all there is to becoming a great animal trainer, but it’s a […]

[…] is my firm belief that as trainers we can be inspired by different scientific disciplines – and the field of emotions is one of […]

Oh, how nice to stumble upon your blog! I have had the post open a few days before actually take time to read it. But the topic was interesting enough to keep me from shutting the blog-window down.

Im in the early process of training animal. I got a dog last fall, and now I need to make her “work”. I use the clicker method mostly at the moment, and it works pretty well. The times it doesnt work is because of me or my dog, not in the right mood.

But I think your post is very important. To learn and to remember and practice your skills, it is not an easy task. After all, all creatures are individual and what may work on one animal maybe dont work on the next one.

I myself doesnt have a big Idol in the animal training world. Maybe because I havent seen one in action, or because I read lots of books from many different trainers. I try to sort what can work for me, and what do all the trainers agree upon.

It is for sure an interesting topic!

What I dont like is people who think they know it all. Sure, I have read books about animals all my life, but I know I dont know everything. I will never get to know everything about animals. But just because I have lots of theoretical knowledge doesnt mean I can use that knowledge in the right way. And I would love to read more and learn more, both from books and trainers showing their skills.

But there are always people who think they know, and have been encourage “You are so good”. Besser-wissers you know… Wont listen to anyone elses opinion and everything they do is right.

They should read your blogpost too! 🙂

Anyway, I have found a new blog to follow! Looking forward to more interesting posts!

Hey Josefin,

Interesting observation! I get less cocky with age. The more I learn, the more I realize how little I know… much more humble nowadays than I used to be! 🙂 //Karolina

This is a wonderful piece. I thank you greatly for putting it out there. I have been struggling for the past two to three years now, trying to figure out which training style or training ideologies to which I want to aspire. I have done the marine mammal care and training internship at the Shedd Aquarium under Ken Ramirez and his wonderful and talented staff trainers. I followed that internship with the Navy Marine Mammal program in San Diego, where I was exposed to a whole cornucopia of training styles and beliefs. Dare I say that they were polar opposites in some respects. Shedd, as you may already know, boasts a very tightly organized and regimented training program for both the trainers and the animals. As an intern there, you get very limited access to the animals and are forbidden from interacting with them in any way unless a trainer allows you to do so. At the Navy program it seemed to me much the opposite. I was one of 14 interns, most of which I outaged by 20 years or more. I had quite a bit more experience than the rest of them and, as I was to find out later, quite a bit more experience/knowledge – or so i was told – than some of the trainers there as well. Though it may sound rather glib, the Navy trainers use a style of training that is more or less fast and loose. Going from the Shedd Aquarium internship to the Navy internship, I was going from extreme structure to much less structure. Some aspects of it I really liked, i.e. being handed a bucket of fish and being told to maintain established behaviors with a dolphin as long as they get their food for the day; and some aspects really challenged what my thoughts and beliefs were from being trained at Shedd Aquarium.

For instance, the Shedd Aquarium trainers are forbidden to use time outs. They are encouraged to use LRSs as long as it is appropriate, but walking away from a training session in the middle of it is is nowhere to be seen in their training regimen. The Navy Marine Mammal trainers, however, DO use timeouts….. more often than one would think they should be used.

It took a lot of getting used to, but after speaking to a few of the trainers, I realized that the outcome of these animals’ training programs prepared them for a purpose that was much different than the animals at the Shedd Aquarium. The Navy dolphins and sea lions begin their training as youngsters and, hopefully, eventually, become competent enough to be deployed anywhere in the world where they are needed for the Department of defense. Most of these projects have deadlines and are funded based on preparing these animals to meet these deadlines. They do what they need to do (while keeping the animals physically and mentally healthy) in order to produce a “product”/animal that will get the job done.

It has been two years since I’ve been exposed to working with marine mammals, but have had the pleasure of learning from elephant trainers at the National Zoo, while maintaining my education in dog behavior and training through workshops and online courses, taught by different trainers with different training approaches. I’m realizing that it’s not all black and white. So when I read this piece of yours, it really resonated with me. Now, instead of stressing and struggling over who is right and who was wrong, I’m beginning to take bits and pieces from everybody to form my own training toolbox.

I look forward to reading more of your writings on different topics of animal training in the future.

Dear Jennifer,

Thank you so much for sharing your journey! I can definitely relate to your frustrations, and perhaps I should also have added “purpose of training” as one category that will heavily influence the ideology that permeates the walls of a specific facility or organization. Glad to hear that my post was helpful to you, and looking forward to further discussions! 🙂 all the best, //Karolina